RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Cynthia May issued key-hole bulletins and a husky whisper.

HE bedroom had looked ordinary enough in the morning; a cheerful place, filled with commonplace furniture and hung with flowered chintz. When I peeped in, during the afternoon, it had taken on a sinister and unfamiliar appearance. White sheets and cloths were spread over everything. Bowls, sponges, and mackintoshes were being arranged by a strange woman, whose costume seemed largely composed of the same cold whiteness. Under the window was drawn up a table.

The sight gave me a queer feeling in the region of the throat, for here—in a few minutes' time—one of our number was to undergo the ghastly ordeal of the Knife.

As I stood, a girl peeped over my shoulder, and then shrank away—tearing at her handkerchief.

"How awful it looks! Oh, I can't stand it! I can't!"

Her voice rose ominously, and the hostile-eyed woman in uniform crossed the room and shut the door in our faces. I don't blame her for her action, for if ever the principals in a grim fight were hindered by the horrified curiosity of the loafers that fringe the ring, they must have been those hastily-summoned surgeons and nurses.

In point of fact, the entire atmosphere was soaked in panic, and everyone in the house had been sopping it up since the early morning. Imagine a week-end party, in top-hole holiday spirits. Take the dominant spirit—a man of solid bone and brawn, animated by the spark of devil so dear to the hearts of women. Crumple him up suddenly with a torturing pain. Call in your specialist, and await his verdict of "Instant operation!" Do all this, and then you'll have some inkling of the consternation and funk that filled every soul in Boar's Head Court since the sudden illness of Terence Dashwood.

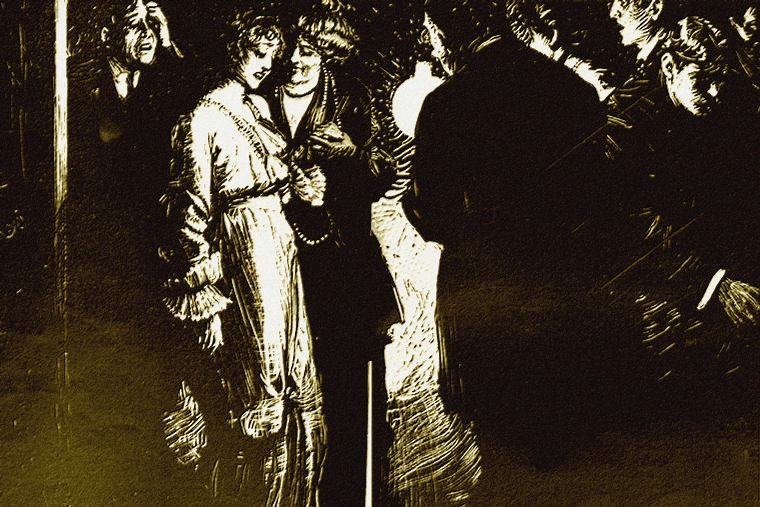

As I gazed in dismay at the girl beside me she began to work herself up still farther. Leila Wales was composed chiefly of the dangerous material of nerves.

She began to speak rapidly.

"I caught a sight of the specialist as he went into the dressing-room. A hateful little grey man, with cold eyes. And that awful stony nurse told me she loved her work. She's gloating over it. Oh, they're inhuman! We can't leave him to them!"

"All this is pure hysteria," I answered. "You must try to calm yourself. You know perfectly well that everything that science and humanity can do is being done for Dashwood. He has a fighting chance. No man need ask for more."

In my efforts to keep the demi-semi-quavers from leaping from my heart to my voice I had frosted my tone pretty liberally. Leila Wales turned on me like a fury.

"It's easy for you to talk. You—who haven't a finger-ache! You haven't to go under the awful knife. Oh, you make me hate you!"

With a fresh sob she tore down the corridor. I turned guiltily to meet a couple of men and a woman, who had also been drawn to the area of the operating-room. They bore, in common with everybody, the tense expression of congealed excitement.

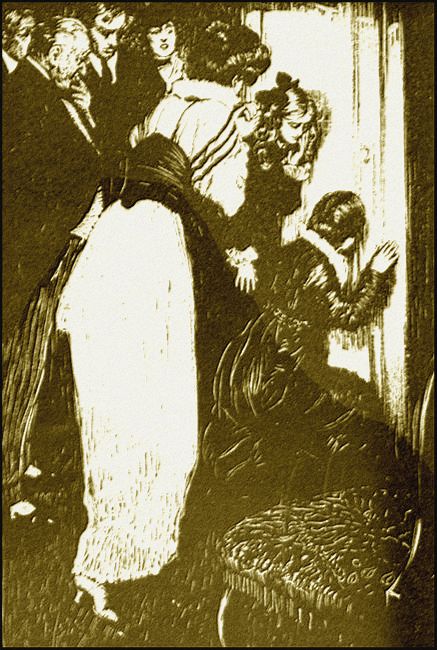

As the woman—Cynthia May—flopped on her knees to the key-hole, in a swirl of cherry-coloured draperies, one of the fellows turned to me, reproachfully.

"At it again, Piper? Exercising your talent for wounding? At the risk of letting it rust, you might have spared that poor girl to-day. Everyone knows she's keen on Dashwood!"

Oddly enough, everyone did not. I, for one. But I did now, and from my sensations my feet and hands seemed to have been suddenly transferred to the neighbourhood of the North Pole.

The little group at the door was swelling in numbers, and the ghastly excitement grew as Cynthia May issued key-hole bulletins in a husky whisper.

"I think they're wheeling him in. They're all getting in the way and crowding. I can see nothing but white. Oh, dear! I'm sure I caught the glitter of a knife. There, again! A-ah! Can't yon all smell it?"

The sickly, clogging odour of chloroform stole into the corridor. Leila Wales, who had crept up to the group, shied off at its breath, like a colt that has stepped on a hot cinder.

We turned to watch her as she staggered away.

"She should take sal-volatile," suggested a girl.

"She takes it hard," commented another, her words making an idiotic sequence.

But Jayne—a medical student with a long, white face, like a Jack-o'-Lantern—looked grave. He riveted his attention on me as he spoke.

"It's more serious than you think. Ever noticed that girl? Hasn't she struck you as heart?"

In my painful relations with Miss Wales she had struck me as anything but heart, but I nodded, all the same.

"That vivid colour, now? All heart! And I tell you this. We all know it's touch and go with poor Dashwood. So if she keeps on working up like this, by the time the op's over she'll be pulp. If he pegs out, she—well, she won't stand the shock."

"That would be a pity."

I did not recognize the formal voice that spoke, but it must have been mine, for they all turned and glared at me.

"Can nothing be done? Can't we distract her attention?" asked Bartlett, vaguely. "Talking's no good, as we've all found out."

"Only one thing would do it," answered Jayne. "A counter-irritant."

"A what?"

We all hung on the pallid youth's words, for, unwholesome-looking brute though he was, he seemed to speak with the ring of authority.

"Anything that would set up a rival agitation. You know the effect of a shock on a raging tooth-ache. A slight accident might divert Miss Wales's attention. But, unfortunately, one could not be stage-managed on the spur of the moment."

"Why not? Surely we can do something." Bartlett was still vaguely eager.

"Because it might be dangerous. An unrehearsed contretemps might lead to unexpected results."

Pompous words! I remembered them later on.

"Well, if you really want an irritant for Miss Wales, I should think Mr. Piper would act as a very effective one."

You remember my name is Piper? Of course it was a woman who spoke. In my case, I should be very sorry for any poor measure of affection I might excite that could not pass "the love of women" with the utmost ease and romp in a winner.

Everyone laughed, with one exception. Again, myself. Nature had undoubtedly made a very poor job of my face, and perhaps it was her slackness that has made me such a fierce opponent of any feminist movement. Yet, to my mind, it was hardly humorous to be the special antipathy of an exceptionally beautiful woman.

Did I mention that Leila Wales was beautiful? Therefore, although it is generally conceded that chivalry is a dead commodity, and to say that five able-bodied men in full possession of their faculties would die for a woman, is a pure piece of sentiment—all the same we tugged at our collars miserably, and felt that to do nothing was at least bad form.

At that moment Turner, the son of the house, came out of another door.

"Clear off, every one of you, this minute!" he said, herding us along the corridor and down the broad staircase. He vouchsafed us a few crumbs of information, however.

"Good old Dashwood! Went into action game to the last. Might have been an innings at cricket."

Everyone broke into a chorus of gulps.

"Thundering good man we've got for the job. Mycroft's the best man in the North. Insignificant little chap, eh?"

As we started to sort ourselves out into restless groups, preparatory to a nomad afternoon, I drew Jayne apart.

"About Miss Wales," I said. "I admit your point of view. She wants a blister. Ahem! I'm ready to be that blister."

As he merely gaped at me, I went on.

"I pledge myself to put Miss Wales into such a fury of indignation that she won't give another thought to Dashwood until he is recalled to her thoughts."

"Really! And how do you propose to do this?"

"I propose," I answered steadily, "to—propose. To ask the beautiful and superior Miss Wales to marry—me. It is the only way. And, in view of my extreme popularity with women I can guarantee the result."

Jayne's eyes nearly bolted from his head.

"But will you get her to hear you out?"

A significant question. Shows he had gauged her exact abhorrence of my unlucky personality.

"That's the difficulty, I confess. Nothing short of locking her up with me, in a limited space, where she could not dodge my near neighbourhood, would answer the case, I fear."

Again that wretched student took me seriously.

"I'll undertake that part for you. Get her to go with you to the strong-room, to——well, say, to see a negative, and I'll lock you in, and unlock you again in five minutes' time. Will you undertake to create such an impression in those five minutes that the effects will last until the op is over?"

"It's up to me!"

Here, I must give a word of explanation. You may have noticed the somewhat peculiar name of the house—Boar's Head Court. Originally an old mansion, it had been turned into an hotel, and then back again to a family residence. The strong-room, where they used to store the visitors' valuables, was somewhere in the depths, and, now unused, was occasionally made to answer as a scratch dark-room for amateur photographers.

I went up and addressed Miss Wales, who was still tearing herself to emotional tatters.

"Come with me to the strong-room for one minute," I urged. "I have something to show you. A rather startling snap of Dashwood."

She instantly turned and followed me. Dashwood was evidently a name to conjure with. Lucky beggar—knife notwithstanding!

As we walked down the corridor that ran off at right angles from the kitchen offices, and turned down the narrow flight of steps that led to the cell, I had a fleeting recollection of the fine Dashwood who went into action game. Again I heard the chorus of gulps. Then I looked at the scornful face of Leila Wales, and am free to confess I felt I faced bigger guns. Only the chorus of sympathy was absent, although Miss Wales did her best to oblige with a sniff—one charged with triple-essence of disdain.

In we went—the door was banged, and the key grated in the lock. At the sound, Leila Wales turned sharply on me.

"Who has locked us in?"

Her voice was suspicious.

"My orders."

I spoke calmly although my heart was expanding and contracting like a concertina.

I thought of the ugly, insignificant Mycroft in that upper chamber, who was carving his way through disease to cure, and I felt a subtle affinity with his repellent personality and drastic methods.

Leila went quite red. She looked at me, as though she were thinking unutterable things. But I felt a glow of congratulation, for I was positive that Dashwood was not one of them.

"Will you explain?" she asked, quietly. You all know that ominously quiet voice! "Where is the snap-shot?"

"There is none."

Seeing that I had taken away her breath, I went on rapidly.

"I merely wanted to secure the pleasure of your company free from interruption. In five minutes Jayne will return, and our tête à tête will be over."

Her breath came back with a rush, and then—she began to talk. I'm putting it mildly, leaving you to guess at the full torrent of her eloquence. But it's my duty to give you a hint, and add you might find it quicker to guess what she didn't say.

As I listened to her flow of indignation it gave me something akin to a prick of pride to feel I had power to call up such a vivid display of personal feeling. But my pride was swallowed almost immediately in a pang of pity. Just as the utilitarian deplored the wasted motive power of the Falls of Niagara, so I saddened to think such splendid force should be turned merely to slate a fellow-mortal. Well, the gods be praised! At least, she'd clean forgotten Dashwood.

Rapidly I made my plans. It would be better to keep my thunder-bolt for the final minute, as it would have to last for some time after her release. My course was plainly to inflame her for its reception.

I took out my watch.

"I have something important to say," I remarked, "but it is too good to be wasted on you in your present hysterical condition. I will give you five minutes in which to find yourself. Then you may be able to do it, and me, justice."

She gave a violent start of temper. I'm positive Mycroft never jabbed home more surely. Stuffing her fingers in her ears she faced me furiously.

"I don't intend to listen to a single word. Nothing you can say would interest me. Everything you say is odious. Your conduct is inexplicable, even in you. I don't believe you ought to be at large. You ought to be locked up."

"I am," I reminded her.

In the ruby glow of the lantern we glared at, each other. Her eyes were dark with resentment. Then, to escape from her gaze, I watched the minutes play "Follow-My-Leader" slowly round the white face of my watch. I wondered what it would feel like, for one minute, to be a fine lump of a chap like Dashwood—to swagger instead of cringe, inwardly at least—to know success instead of failure. Odd to think that even now he was just so much helpless tissue under the knife.

A sound roused me from my reflections. It was the drag of Jayne's footsteps coming to release us.

I moistened my tongue. It was now or never. The cords began to swell on my forehead like leather after rain.

"What I mean to say to you—" I began.

"I'm not listening," broke in Leila, furtively removing one finger-stopper.

"Is to Good heavens! What's that?"

We heard the sound of something pitching down the stairs like a half-ton of coal.

"What's up, Jayne?" I sang out.

A mighty amount of heaving, slipping, and soliloquy followed. Then Jayne's voice answered:—

"Caught my foot—that's all, and fallen down. Hurt my leg, too. Wait a bit!"

As we held our breaths we heard the sound of a smothered groan.

"Crepitus!" Jayne spoke in a tone of gloomy triumph. "I've broken it all right. I should diagnose it as a simple fracture."

"Yes. Sorry. What about us?"

"I know, I know. My head's swimming a bit. I've dropped the key somewhere, and the candle went out when I fell. Can't feel it anywhere. But—it's all right. I'll crawl up and let the others know. You'll be let out, sooner or later."

We heard him drag himself painfully up the steps. Then, all at once, the rustling and scuffling stopped abruptly.

I slued my head round at Leila, but her ears were evidently not so keen as mine. She had not grasped the fact that Jayne had fainted.

You don't seem impressed, although this is the very crux of my yarn—what I've been leading up to from the first. I'm not surprised, however, for I didn't tumble to it myself, at first. But in less than two minutes I had run my head against the fact with staggering force.

At first flush it sounds harmless enough. Jayne was bound to come to, sooner or later, and it was only a question of waiting to be liberated. Sooner or later. In point of fact, too late.

Ever tried covering a lighted candle with a wine-glass and watching its flame flicker out? That was our position exactly. The strong-room—a mite of a place—was absolutely air-tight.

We knew this and, when developing our plates, always left the door ajar, as there was practically no light in the passage outside. Jayne's promise to let us out in five minutes was based on the same knowledge.

His words came back to me in that moment—"An unrehearsed contretemps might lead to unexpected results." I could have laughed at the simplicity of the events which had turned our counter-irritant into a deadly poison. The side-issue had swollen to monstrous proportions, completely engorging the primary tragedy of the operation.

I'm no scientist—merely an unprepossessing individual with a nervous system for ever on the hop. So I could make no rough calculations as to how soon we two should exhaust the air. Nor did it seem feasible to pack up my share and, with traditional nobility, proffer it to my companion. But it was a fact that we had been draining our supply hard for over five minutes. It seemed to me that even in that moment, as we waited, the air thickened visibly, like milk when you drop in rennet.

To one thing, however, I was pledged. Leila must remain in ignorance until just before the end. I could not sling her blindfolded into Eternity, but at least she should be spared the torture of fore-knowledge until the last possible moment.

I thought all this over quietly as I faced the situation. To my mind, in real life, one takes a stunning blow quietly. It may be that the brain is too dead to cope with the position. Or it may be that, without our knowledge, the spark of immortality imprisoned within us is straining to be free. In any case I know that, bar an under-current of horror, I viewed the affair in a detached, critical way.

Then I looked at Leila. Brown hair, vivid in the red light. Grey eyes with a wash of blue. Ripe, rounded cheeks. I wanted to stamp the picture indelibly on my mind, so that if we missed each other in Shadow-land I might remember her through the ages to be. It seemed to me, however, that she was eyeing me suspiciously, so I returned to my former tactics of tickling her animosity. Never was a sorrier task given to mortal—this petty sparring —as preparation for the eternal "Good-bye." Instead, I wanted to—but, never mind!

"As we've still a little time together," I said, with a ghastly double meaning, "I should like to ask you something. Why, ever since we've met, have you treated me with such persistent dislike? There is no reason for so much bitterness and disdain. Remember the adage—'A cat may look at a king.' I may reasonably claim superiority to a cat."

"Why? For one thing, you haven't nine lives."

The flippant retort was so sinister a reminder that I drew a long breath The next minute I cursed myself for reckless waste.

"Nevertheless," I went on, "I have a little value as a human being. On the other hand, you are not a king. You are just a woman—one among many. What are you so proud of? Looks? In England alone there are hundreds of women prettier than you."

I did not believe it, but I rejoiced to see the angry light coming back to her eye.

"Thousands!" I was growing reckless with success.

She wiped her face. But, thank Heaven! she did not know why she did it. I did, for to my mind the air was growing stale as last night's smoke.

"And you're proud of your attainments," I proceeded, turning the knife round again. "In the name of common sense, why? Why should you give yourself airs on the strength of being able to speak French and German? Any half-starved Swiss waiter is a better linguist than you."

Again Leila Wales used her handkerchief.

"When I first met you," she said, "I knew you were a horrid, snubbing man. But you are even horrider than I thought. I put down your hateful air of superiority to the fact that I worked in the Woman's Movement."

"Woman's Movement?" I waved my hand in the air, and noticed with a shock how the fingers trembled. "It simply amounts to the fact that you're doing badly work that men would do well."

"What a lovely reason!" Leila seemed to be enjoying herself. "What proof have you ever given of masculine superiority? You are a sneering cynic, who have never lifted a finger on anyone's behalf!"

For the life of me I could not keep back a smile at that. When one considers the exact position, there was unconscious humour in her charge.

But even as I smiled, certain disquieting sensations were crowding over me. I could not keep from fidgeting, and my breath was growing faint and shallow.

"You are very clever at finding fault," went on Leila. "It would be quite interesting to hear what you expect of a woman?"

I would rather not have spoken, for I knew my voice would let me down. But I took up the challenge, speaking in reedy tones.

"I'd rather have a woman who darned stockings instead of being a blue-stocking. I'd rather her be homely than beautiful. I'd rather she spoke one language—her own—kindly and gently, than all the languages in the world."

It was no good. I had to stop. There was a singing in my ears and a mist before my eyes. My horrible suspicions were fulfilled. I was going under first.

Well—now she would have to know! But, as I sought for words, she turned sharply round on me.

"What's the matter?"

There was such an unusual note of sympathy in her voice that I forgot all.

"Leila," I said, "what I wanted to say to you was this: I loved you from the first moment I saw you. I shall always love you!"

To my astonishment she caught my hand.

"Then why have you been so hateful and superior, John—dear?"

John! She had called me by my name! And tacked something else on as well.

Before I could grasp the significance of her words there was a rattle at the door, a gust of fresh air that almost knocked us over, and the light of a lamp. It seemed to me that a crowd of faces looked in at us. A buzz of voices arose, and in less than a trice we were in the passage. I saw Jayne, pallid and limping, and then I realized that Turner was speaking.

A buzz of voices arose, and in less than a trice we were in the passage.

"Just over!" he cried. "A splendid success. Everything O.K."

I stared blankly at Leila, who held my hand.

"Good gracious!" she exclaimed. "The operation. Why, I'd completely forgotten it!"

The faces round us broke into significant smiles.

"Aha! The counter-irritant!" said one man.

"Good man, Piper! Congratulate you on its success!" said another.

But he did not know then exactly why I was to be congratulated. Neither did any of them know, until later, why I suddenly pitched forward and fainted.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.