RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"ONE gets tired of hearing the trite remark that often the bravest deeds are those that receive no recognition," observed the Colonel, "For my part, I'm prepared to include the noble army of obscure heroes in my creed. But—when I look back on the dark days of the Mutiny, the one man I would like to decorate had his name blackened by two of the vilest charges it is possible to bring against an Englishman. What was more, he had to plead 'Guilty.'"

The keen eyes of the veteran grew slightly misty, as he looked away from the trim lawn, flanked with brilliant flower-beds, and bristling with an eruption of croquet-hoops, to the far country, where the vivid green of June—blazing in the sun—burned into a blue smoke of distant hills.

The lads by his side gazed with curiosity at his wrinkled face, tanned by tropical suns to the colour of strong tea, its hue only just beginning to fade before the yellow peril of liver. They were nice, pink-and-white-boys, both—in training at a military college; at present they played polo very well and very gamely for their country, just as later on, they would fight for her very badly, as they had been taught—and very gamely.

In spite of their visible impatience the Colonel began his tale in the slow, meditative manner of one, who, having run through his portion of time in the course of a long life, does not scruple to draw on eternity.

"This man of whom I'm thinking," he began slowly, "answered to the name of Ansom. At least, he did, before the bad business. I doubt if he had any chance of doing so afterwards, as his name was then judged unworthy to be uttered by decent lips.

"No, my lads, calm yourselves! He was no soldier. Your profession is not going to be dragged in the dust in this story. He was an anomaly for India, being neither military, Government, trader, nor missionary. He was well-known to both English and natives in the sense that they were familiar with his tall, slouching figure, his thin, monkish face, and his moral peculiarities. Otherwise he was little known.

"Although he was no parson, he was commonly called the padre. It was the popular way of reconciling his solitary habits and his strict and minute code of rectitude with the personality of an ordinary Briton.

"His was a curious face; in a manner of speaking, transparent—for in moments of stress you saw through it, as through a glass darkly, the muscles throbbing in his cheeks, like the springs of a steel trap. His eyes were prominent, and ever shifting in their sockets, following every flicker of his nerves.

"As a matter of fact, he was an abnormally conscientious man, who followed a rigidly Christian line of conduct, not through loyalty to the Leader, but through a most real and potent fear of the Devil. He honestly believed the doctrine that if his hand offended, it were better plucked off than left to spread rot amongst the sound members. And he was ever on guard to preserve the scrupulous cleanliness of his tongue, for he held that to utter a single lie, or the name of his Maker in vain, was to instantly consign both his body and soul to everlasting damnation.

"A curious creed in these slack days when no one fears penalties. Wait and hear what it cost him, in the year 1857 on that memorable evening on the 10th May, when the call of the church-bells was the signal for the smouldering native rebellion to break into the first spurt of the fire at Meerut. You've often heard the tale of how the 3rd Native Cavalry stormed the gaol where the eighty-five martyrs of the greased cartridge affair were confined, and then started to slaughter every white person in the town.

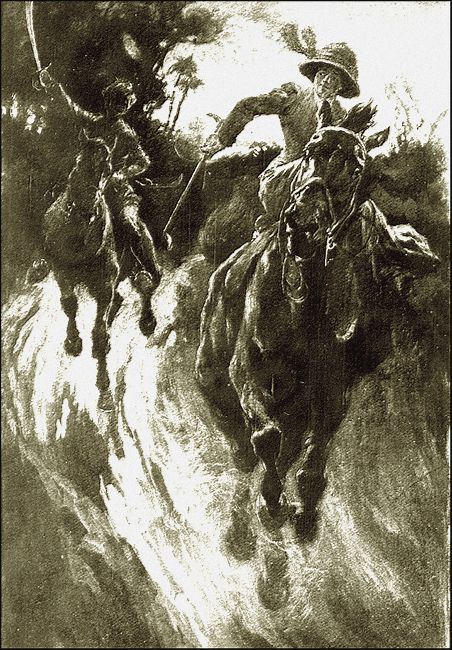

"Thus it chanced that barely had the sun-baked soil of India sucked up its first drop of European blood, when an Englishwoman was galloping for her life, through the network of native streets, the special quarry of a man of the 20th Sepoys, which was the first regiment, you remember, to fire on its officers.

"This man had recently been in England, and whilst there, had received much flattering attention from a certain family called Tallboys, on account of his abnormal skill at cricket. While he won their local matches for them, he received some coaching on his own account, in the Gracious Game, for Mary Tallboys, the daughter, was indiscreet enough to flirt seriously with her visitor.

"When she joined her brother in India, not long afterwards, she found that the values were shifted. The taint of the tar-brush put the Indian on the black list of her acquaintances, and she took the first chance of repairing her error, by ruthlessly cutting her former friend—a mean action which naturally implanted in his heart an ever-growing sense of injury and desire for revenge.

"She paid dearly for her English snobbery, for on that night of the 10th May, the values were again shifted, and at the sight of a superior officer, shot on parade like a rabbit, the Sepoy sloughed his whole skin, with its little bit of England grafted on to native stock, and with atavistic celerity reverted to that primeval period when we were all stark savages.

"Picture then, this poor, silly county-bred girl, her English roses still fresh upon her plump cheeks, her blue eyes glazed with fright, flying before the pursuit of a brown devil, who brandished his sword in the rays of the setting sun, and yelled for vengeance!

Flying before the pursuit of a brown devil, who brandished his

sword in the rays of the setting sun, and yelled for vengeance!

"It is supposed that, out of sheer panic, she struck the Delhi Road—only conscious of one desire to escape from a nightmare, where, in the flicker of an eye-blink, a quiet Indian town was changed to a reeking shambles. She was leading well, when the horse of her pursuer slipped and stumbled and fell, both animal and rider rolling over together. It was a bad toss, and by the time he was remounted the Sepoy had lost sight of his quarry for the moment, in the network of streets. He appealed to the passers-by, but with little success, for the lust of slaughter was already sending them hot-foot on similar errands of blood. Thus he received two reports—one that an Englishwoman, riding like the wind, had whirled along the Delhi Road, before one could stop her; the other, that she had passed into the house of Sahib Ansom.

"Thus my man comes into the story. The tale of what followed was related to me by a native who had the words from the Sepoy's own lips. So graphic and picturesque was his account that I feel I was a spectator of the whole scene.

"At the check, the Sepoy stopped in momentary hesitation. Every school-boy at 'hare-and-hounds' knows the value of a long start. It is almost impossible to overtake the quarry if the pursuit has been delayed too long. He knew that the Englishwoman rode better horse-flesh than his, and was, in addition, a lighter weight. It was just humanly possible for her to win through the thirty-odd miles to Delhi, before he coursed her down. On the other hand he dared not lose the chance of finding her in Ansom's house, like a rat in a trap.

"A sudden impulse fired his brain. He entered the shuttered house to find Ansom, pallid from the heat of the long day, and clad for coolness, in his sleeping-suit, lying on a long cane-chair, smoking a cigar. The Sepoy's keen eyes noticed that the weed had burnt irregularly and that at his entry, the muscles of Ansom's face twitched convulsively, like a dying snake that awaits the sunset.

"'He knows,' he said to himself.

"He stood before Ansom, the blue turban of a Mohammedan on his head; the sun came in through the chink in blood-red streaks, playing on the brass-work on the great curved blade—destined to rip up many an English body. He looked at the pale, throbbing face of Ansom and he laughed in his beard.

"'Now shall I know the truth,' he said. 'This is one who fears to tell a lie, lest he burn in the hottest hell. Which way went the Englishwoman? Speak!'

"There was a pause during which Ansom looked at the speaker, as though deprived of all power of volition or thought. Then the pupils of his blank, staring eyeballs split, so that one could see the thoughts racing hither and thither, as they pulsed from the frenzied brain.

"The Sepoy laughed.

"'Quick! Time presses. The truth, and you shall go unscathed! Lie, and'—he raised his heavy blade—'you shall go straight to the God you worship, your lie wet on your lip.'"

The Colonel stopped and moistened his throat with the mineral waters prescribed to appease his tyrannous liver.

"It is rather interesting," he said, "to try and follow the working of Ansom's mind at that moment. I can see that you fine fellows wonder at his hesitation. Sooner than betray a woman, you'd be split up as cheerfully as one splits an infinitive. But I want you to remember that Ansom's religion was a real thing to him—as real as the stripes on the Union Jack to you. He honestly believed that a lie would send him to everlasting damnation.

"The Sepoy had him pinned down with a prong, as one nips a viper in the cleft of a forked stick. The whole thing happened in about two minutes, so I leave you to imagine how he stoked his brain to action, all engines throbbing at full steam.

"Then he opened his lips.

"'I will tell you the truth,' he said, and his voice sounded like a bray.

"He stopped, and glanced involuntarily at the clock on the shelf, and then his eyes shot a scared look in the direction of the Delhi Road. The Sepoy stood like a brown image, but his glance flickered after Ansom's, quick on its train like intelligent lightning.

"'I will tell you the truth,' again said Ansom.

"He stopped to moisten his lips, now dry as chaff, with his tongue. It was his honour against his soul. A woman's life against his dread of eternal death.

"Which would win?

"'I will tell you the truth,' he said the third time, as though he would gain moments that were more precious than rubies.

"'On my word of honour—as an English gentleman—the Englishwoman is here, in this room, in that locked press.'

"With quivering hand, he barely indicated the tall carved cupboard behind him, while his eyes shifted involuntarily in their former direction.

"There was a moment of silence, after the words of betrayal were uttered. Ripples of agonised torture passed over Ansom's face—pale shadows of the pains that rent him within. One could see that the Fiend had clapped his hand on him and dragged him down to a smoking hell.

"Then the Sepoy burst into ironic laughter. He laid his hand on the press.

"'And the key? In the tank yonder? So, so. And how long before we recover it, or force the lock, to find the press empty? And while the precious moments pass, the woman will be flying ever farther from me, down the Delhi Road. Already the start is great!'

"He turned and looked into Ansom's eyes.

"'You have lied, and lied transparently, after the manner of your kind, who are but men of glass. Have I not lived in England? And do I not know that formula—that sacred formula —"An English gentleman"? Had you sworn by your God, I might indeed have questioned—wondered. But it is not with that sacred oath—"The word of an English gentleman" that a sahib sells his countrywoman.'

"He raised his blade.

"'But from your lie have I the truth. You have valued your honour and a woman higher than your God and your soul. So—die!'

"Had I been there I should have held it a great moment. Even though the lie were in vain it was a magnificent triumph that one of our race had bought a woman's life with his soul.

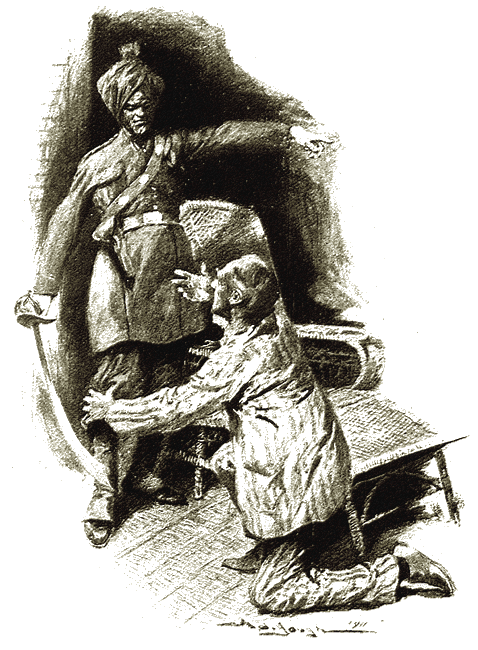

"But hot on that splendid moment came a scene of shame, the bare thought of which hurts. For as the wind of the sword whistled through the air, Ansom fell to the ground, and clasped the Sepoy round the knees.

"'It is the truth!' he cried. 'Test it! Spare my life. Oh, spare my life!'

"The look of grudging admiration passed from the Indian's face.

"'The Englishman kneels.' He laughed shortly. 'Your life? Yes. On this condition.' He pointed to a photograph of Queen Victoria the Good which stood on the shelf. 'I would have made you defile your flag, but you have not one here. But, destroy that picture of your Queen and spit on the pieces!'

'Your life? Yes. On this condition.' He pointed to a photo-

graph of Queen Victoria the Good which stood on the shelf.

"The muscles of Ansom's face worked as though urged by machinery. Like a whipped cur, he crossed to the shelf. He took and defaced that piece of cardboard that stood to him for pride of country, while the Sepoy stood and laughed.

"He sheaved his sword.

"'Keep your life, dog!' he said. 'You have bartered your soul for a woman, and your sovereign for your life. Praise be to Mahomet I am no Englishman!'

"He vaulted into his saddle and his hoofs could be heard thundering on the dry road at a rate sufficient to overtake any fugitive. Four hours later, he came upon her riderless horse, cantering along the road, and found that he had been fooled. Before his return, the woman, disguised as a native had been smuggled across to the British lines, where alone safety was to be found that night of dread. Oddly enough she survived all the horrors of the Mutiny, and in the end married a V.C."

The lads stared as the Colonel ended his tale.

"What do you mean? She was in the press the whole time?"

"She was in the press."

"Then the skunk betrayed her."

The lad's voice was full of incredulous disgust.

"Everyone thought as you do, Sawyer. The disgrace of that deed was blazened from station to station and stuck to his memory after he took vows and ended his life in a monastery. Yet that's the man for my ribbon and cross!"

The Colonel stopped to laugh at the disgusted faces.

"Come, lads. I had the story from his lips. He's had a rough passage, but he's passed over now, and let's hope it's been made up to him! When the Englishwoman fled to Ansom's house, he was resolved—even as you or I—to save her, at all personal cost. Remember what that cost implied to him! When the Sepoy put that question to him, he was resolved to damn his own soul to save her life. But then he saw this point.

"Would a lie be sufficient to save her? Had he said that she was far away on the Delhi Road, it was more than probable that the Sepoy would instantly have doubted, and searched the place. Although the man had credited him with truthfulness it is not in Oriental nature to have real belief in veracity. Ansom understood human nature, and he knew the subtle workings of the Indian's mind, who read human nature as you read a primer. He guessed that the Sepoy knew what an Englishman valued most, and that the truth—too hideous from its cowardice and treachery in the form he presented it—would fail to gain credence, and pass for a lie. Therefore he deliberately threw the Sepoy off the trail with those furtive glances, as if he knew that every moment was precious. And therefore—he pleaded for his life, because he alone could save the woman. Had he been granted the boon of death, she would have been left to perish miserably in the locked press."

There was a long pause. Then the elder lad spoke thoughtfully:

"How do you know his tale was true, Colonel? He valued his soul very high, and he held a lie to be the price of it. Well, when all was said and done, it was his own score. He managed to save his soul."

"That's so. That's the view every man and woman in India who heard the story took of his conduct. Then how do I know he told me the truth? By this."

The Colonel's voice rose an octave.

"Before Ansom was a Christian, before he was an English gentleman, he was a man. I know he loved that woman, in secret, with all the depths of his soul. Yet—he faced the agony of suspense when her life hung in the balance. Again—he grovelled in the lowest depths of shame, when he renounced and insulted his country and his Queen. Lastly—the supreme test of all—he faced that woman when he opened the press—the woman who had heard herself betrayed, and could neither understand, forgive nor forget. The woman he loved.

"Lads! I tell you that man had passed through triple damnation. Having counted the cost, he had been in three separate hells. How then—should he fear—one?"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.