RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

It was a very crest-fallen pony that meekly returned to stables-

"I DON'T care what a man is, as long as he can ride straight!"

Lady Nina Glendower tilted her bowler hat and stared meaningly at the handsome young farmer. That he did not miss her drift was evident by his conscious laugh.

"Well, I must say," he confessed, "when I'm leading the field in a hard run or riding one of my gees to win in a point-to-point, I don't feel exactly inferior to any belted earl."

"Not you! 'A man's a man for a' that.' I always say straight out what I think."

Lady Nina kicked vigorously at the blistered paint on the gate to emphasise her freedom of speech. Young, beautiful and ignorant, she considered herself privileged to ride rough-shod over the conventions. The presence of a gardener at work close by hampered her no more than the fact that she was conducting her flirtation practically under the windows of the lodge.

Edmund Saxon hesitated before replying, although shyness was alien to his nature. Then, with customary bluff, he rushed in boldly.

"Seems to me all such rot! Here's you—smart as paint, young, set on riding and all that. Here's me—a two-year-old in sound condition, so to speak, keen as mustard on everything you like. We've been on the land every second as long as your people. Yet, every dead-alive big-bug in the county, as well as the batch of them underground, would be galvanised to life with a shock of horror if they heard that you and I—well—wanted to get married!"

Lady Nina coloured slightly at the audacious speech, but she tossed her head.

"The deuce take the county!"

She spoke recklessly for effect, but Saxon applauded her unconventional words.

"I admire your spunk! But the question is—Are you prepared to back it?"

"Why not?"

"This way?"

"What's the odds?"

Their lips met in a kiss.

The gardener looked up at the sound, then spat on the ground contemptuously. But Lady Nina heeded him less than the clods he turned. Her attention was attracted by a second witness of the tender scene.

A woman, mounted on a piece of horseflesh that seemed, like the Fuzzy, to be "all 'ot-sand and ginger," sped by with a clatter of hoofs. The girl had only time for a snapshot vision, but it was enough to make her stare after the retreating rider. The beauty of the woman's face was arresting, although its lines had been marred by Anno Domini—and something worse—and the curves of her figure, set off by the tight black habit, were magnificent.

Nina caught her breath.

"Whoever's that?"

"Mrs. Sam Leek. They keep a pub—'The Royal George'—a few miles back. She rides in every race-meeting and show. There's not a man or woman to touch her for a hundred miles round."

Nina's face darkened at the animation in his voice.

"Aren't you drawing the long bow?" she asked.

"Not me! She'd ride the Fiend, if she could get a bit in his mouth, and there's not a man but would follow her down to the Pit itself, where it's to be feared she's heading."

Again Nina felt chilled. Saxon seemed to be unconscious of her titled self. She was suddenly filled with a feeling of jealous enmity against this publican's wife.

"She stared at me as if I were a mite in a cheese," she said haughtily. "Did you notice? The cheek!"

"Ah! That's because I was with you."

In that sentence, Saxon, with native egotism, summed up the situation, as he bracketed the two women together in the running. Lady's Nina's face instantly grew dark with anger.

The young farmer was quick to notice the change.

"Of course she's nothing to me," he added hastily. "She's over forty, and married. Besides, she boozes. Oh, I say, don't go!"

He gazed blankly at the retreating form of Lady Nina. Then, mounting his cob, he rode away over the grassy border of the road.

Gradually his serenity returned as his thoughts dwelt on his latest conquest. In his flirtation with Lady Nina Glendower he was flying higher than any airman, and there was a smile of triumph on his tanned face as he cantered homewards.

Presently he came to earth again as a bend of the road brought into view the figure of a woman, seated on the edge of a horse-trough, while her steed cropped the grass at the road-side.

Saxon's face lit up at the sight. The next second he was off his horse and seated by the side of Mrs. Sam Leek.

"Waiting for me?" he asked, with a confident smile.

"Oh, go to blazes!" The coarseness of the woman's speech—its accent tinged with the local dialect—was strangely at war with the beauty of her reckless blue eyes.

"Think I'd cool my heels for you?" she continued. "I don't go in for cubbing. My old man's worth twenty of your sort."

Although Saxon's face lost some of its confidence, he still continued to gaze with infatuated eyes.

"Your riding at Newton Abbey, Friday, was top-hole," he said. "Congrats. You took the water-jump in style to make a dead man sit up and cough. I'd give something—. Look here! Why haven't you ever a decent word for me? You've plenty of honey for other chaps. Why am I black-listed?"

Mrs. Leek smiled, and much of the coarseness of her face faded in the wonderful fascination of her expression.

"You hang up your hat at too many houses, Eddy. Think I'd enter the running with every half-baked girl in the county? By the way—who's your latest? The flapper you were kissing by the gate?"

Back came the swagger to Saxon's movements.

"That? Flapper indeed! Nineteen, if a day, and a fine girl. That, if you please, is Lady Nina Glendower—the eldest daughter of the Duke of Roseminster. You see, my lady, finer folk than you are only too glad to snap up your leavings!"

There was no finesse about Saxon; his surface veneer of breeding was sloughed at first tilt with Mrs. Leek—revealing the coarse grain of his nature.

His boast only made the woman rock with laughter.

"You young fool!" she gasped at length. "You and a duke's daughter! She's just pulling your leg. It's common talk Lord Townley is coming down the week-end to settle up affairs. The match has been rumoured in the papers weeks past. She's flirting with you to keep her hand in. In love with a back-door acquaintance! If she could buy you at her price and sell you at her own she'd do well out of the deal."

Again she shrieked at the sight of Saxons crestfallen face. Then she put one roughened hand on his coat-sleeve.

"Look here," she said, "I've a sneaking liking for you, because you've a straight nose and a decent seat. Take my tip, old man! Marry some girl in your own sphere—say, your cousin, Miss Preece. She'd make a champion farmer's wife. Moreover, she's fool enough to jump at you. But, if you want to save your face, drop these rotten ideas of rising above your station. It don't pay to be a thruster. Forgotten your pilling over the Hunt?"

Saxon rose hastily and mounted his cob. Mrs. Leek's words had brought up a painful recollection of his surprise when the surrounding gentry, who met him with utmost cordiality at hunt breakfast and ploughing-matches, resented his ambition to wear the pink.

"He laughs best who laughs last," he growled. "It would be a slap in the face for you, my girl, if Lady Nina bolted with me. What will you bet I don't cut out this lord of yours?"

"I'll bet my head!"

Saxon rode off with feigned hilarity. In spite of his tall words, he knew Mrs. Leek had scored. Yet she sat for fully ten minutes afterwards, her eyes charged with anxiety and her head held tightly between her hands, as though she feared to lose it with her wager.

Meanwhile, the girl whose name had been bandied over the horse-trough, trudged up the drive. She always rode cross-saddle, and her long coat, that showed her boots, gave a boyish look to her appearance. As she passed the gardener he touched his hat respectfully, but the look he bestowed on her back was significant. Although the family had been barely a fortnight in the place the Duke had taken for the hunting, every dependent had already formed an opinion on Lady Nina Glendower.

"That a dook's daighter!" the man commented. "My Liz's more of a lady than her. Making herself cheap with all the village lads like a common wench!"

But the puppy that Nina had just hoisted up persisted in washing her face all the way to the house. He knew of the two days and nights, after he had taken poison, when she had nursed him hours at a stretch, the tears trickling down her nose, as she strove to drag the wobbling paws back from Shadowland.

Her father and stepmother were standing on the old stone terrace when Nina approached. Both regarded her with a fixed expression of stony disapproval.

"Where have you been, Nina?"

The duke—who appeared to be made of the same material as the terrace—spoke coldly.

"Rotting about."

The duke's expression changed to a look of tense anxiety. His eldest daughter—fully fledged beauty though she was—in running to an excess of animal spirits at the expense of her brains, seemed unlikely to bring credit upon his name.

The light of rebellion was kindled in her eyes by her father's next words.

"Townley is coming to-morrow, Nina. I have sanctioned his visit, and I hope that you will—Dr—keep yourself in hand, so that matters may be satisfactorily concluded."

"Townley!" Nina made a hideous grimace. "He's not my sort!" she objected.

"A matter for congratulation, and a testimonial to his breeding. And—one word more. We leave here next week."

Nina faced her parents with startled eyes.

"But, Dad—why? This is such a ripping hunting country. And we've only just come. Why?"

"Because of a certain undesirable piece of news that has just been brought to my notice."

The girl collapsed before her father's penetrating stare. It was evident that he had already heard of her flirtation with the young farmer. Simulating an air of bravado, she ran out of the room.

Her eldest step-sister—a pretty girl of seventeen—was having her hair dressed for dinner, when Nina burst in upon her toilette.

"Heard we're off, Lav? Know why? I hardly know whether I'm on my head or heels."

"You might get a clue by keeping your eye on your hat," replied Lavender coolly. She was curiously like a pink edition of her grey father.

"Townley's coming to-morrow, Lav!"

"I know. You may go, Perkins!"

"Look here, Lav! Would you grab at your first offer?"

"Certainly not, unless it were worth my while."

"There you are. It's not. So I pass!"

Lavender's calm voice shattered her premature triumph.

"But I certainly should, if I were you. You see, you've been already talked about, and once in connection with a chauffeur."

Lady Nina gasped at the matter-of-fact words. For the first time in her life she suddenly felt cheapened. Without replying, she rushed away to her own room.

The new feeling of inferiority hurt her pride terribly. As she looked in the glass, and took stock of her rich young beauty, she contrasted her position with that of her sister, Lavender.

"I must be a throw-back," she said at last. "I don't seem born to all this. Lavender and the kids get more respect than me. Wonder why? Well, there's Townley!"

She gave a groan, as her mind reverted to the Saxon era. Her last flirtation would soon be as much a thing of the past as any page of back English history. She thought of Townley well-born, well-bred, well-educated, and then her eyes were attracted by her favourite picture that hung above her head—the portrait of a famous highwayman.

It seemed to her that the bold, handsome face bore a strong resemblance to Saxon. She had a sudden vision of breaking free from the old, restricted life, and riding out into the world, with this caped hero, Gretna Green in front, dimly seen through a golden haze of romance.

She gave a cry of triumph. In the midst of her dejection a thought had struck her. She chided herself for her folly in not realising the fact before. All her life she had kicked against the pricks, but she had meekly put her head into the halter, all the same. Yet all the time a door to freedom stood before her gaze. Outside was open country. She had only to bolt.

In an instant she snatched up a writing-pad and hastily scribbled a few lines.

When the missive was delivered to Edmund Saxon by that evening's post, he raised his brows at the handwriting, which would have disgraced a kitchen-maid. But his face flamed with excitement as he tore it open and read its contents.

Dear Edmund,

It has been brought home to me to-day. I'm out of place here—a misfit. They want to dispose of me, but I decline to have my life made by others. I'll make my own. This is my decision. Sooner than serve in Heaven, I'll rule in Hell. If you care to meet me to-morrow, we'll ride to Slowton and get married there, by special license. And the country may go hang!

Yours, Nina.

In a frenzy of triumph, Saxon tore to his writing-desk,

and covered page after page with his thick, characteristic

writing. He smiled grimly as he gave his letter to a man for

instant delivery. It struck him that the handsome head of Mrs.

Sam Leek was even then tottering on its shoulders.

THE air was raw and sprayed with mist next morning when

Lady Nina Glendower, accompanied by a groom, went for her

morning ride. At the bend of the drive she twisted her head

round for a last view of the house. Never again, she told

herself, would she place foot inside.

She broke off in her whistle to make a remark.

"Après moi, le déluge. You don't know what that means, Foote, but it exactly expresses the present position. Some Johnny or other—I forget who—said it. And now I say it."

"After me, the deluge. A remark made by a dissolute French monarch before the French Revolution," answered the man, glibly.

"Gracious, Foote. Why you know more than me."

"I received a Board School education. And I've learned much living with the aristocracy."

The usual veiled impudence was in the man's voice. Nina was conscious of it, and it spurred her on to action.

"Well, do you know enough to go home and spin some fairy-tale about a dropped shoe? I'd sooner your room than your company this morning, Foote. Here! This'll help you to oil your brains."

A coin passed, and then Nina cantered forward alone into the mist—revelling in her first ecstasy of revolt. She never stopped when she reached the crossroads, where Saxon was waiting for her.

"Follow me, if you can," she shouted, as she tore past.

"To the end of the world." Saxon's reply was the essence of romance, as he thundered after her.

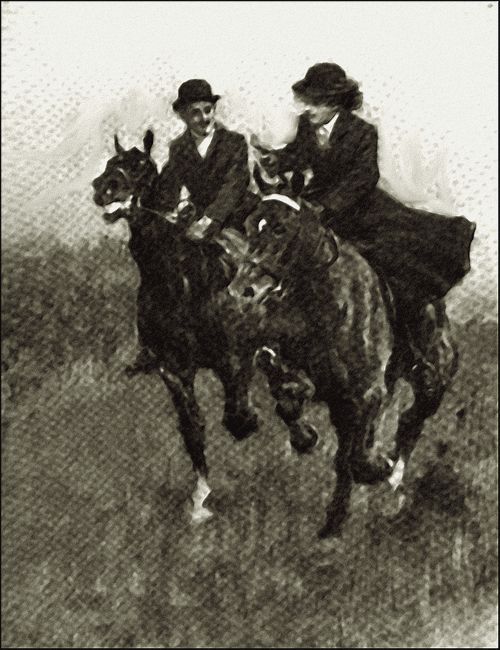

They made a perfect pair as they galloped away over the moor, both young, handsome and in love—the girl with liberty, the man with social advancement.

They made a perfect pair as they galloped away over the moor.

Lady Nina pulled up at last.

"Feel on oats to-day, as if I could last for ever. But we mustn't wind our horses. What did you think of my note?"

"It made me the happiest man on earth. I suppose your governor'll do something for us?"

"What's the odds? I guess I'm brainy enough for a farmer's wife, anyway? Here, what are we stopping for?"

Saxon had drawn rein in front of an inn, over the door of which hung the painted head of a Hanoverian monarch. It was "The Royal George."

At the sound of the clatter of hoofs, a head looked through the window, and next minute Mrs. Leek appeared at the doorway.

Nina stared at her with the same intense curiosity. In the strong morning light, and apart from her horse, the woman seemed made of coarser clay. She looked a strapping plebian in her huge-patterned check dress.

"Morning, Mrs. Leek. Whiskey-and-polly for me, and a glass of cider for the young lady," sung out Saxon.

It was his moment of triumph. He had stopped especially at the "George" to proclaim his win.

A dull mottled red ran up the woman's face.

"Won't you come in and have something to eat as well?" she asked. "It may be you've far to go!"

As Saxon hesitated, Lady Nina slipped from her horse. Besides her hunger, she had a thirst for knowledge, and she wished to see more of this strange woman, who appeared to have the mankind of the county to heel. She was possessed with a sudden longing to get at grips with her.

They followed the publican's wife into a small, musty parlour undusted, and smelling of beer.

Mrs. Leek noticed Lady Nina's start of disgust.

"Pretty ghastly, eh?" she remarked. "I've got a girl, but I don't know what to tell her to do, and I'm in the saddle or behind the bar, all day. Wasn't brought up to house-work. Spent my time in the stables."

"And to good advantage, I hear."

Lady Nina spoke with cold politeness. Again, to her intense astonishment, she scented a rival in this impossible woman.

Mrs. Leek laughed.

"I don't do it for my health. You'll ride yourself, one day, with practice. But you've not had your drink yet. I've champagne fit for—well, special occasions—in the cellar. If Mr. Saxon will come with me to reach some down, we'll see what it's like!"

One eyelid fell in a barely perceptible wink as she spoke.

To Nina's anger, Saxon responded to the signal. There was a light in his eyes she had never seen there before as he sprang to his feet. With bitter jealously, the girl saw that he welcomed the chance of a few minutes' privacy with Mrs. Leek.

"Come on," he said, "and afterwards we'll drink the health of—my future wife!"

Nina saw them disappear through the door. Then, hot with indignation, she hurried out of the stuffy parlour. She had barely reached the road, when she heard the sound of footsteps, and Mrs. Leek ran out of the house.

She put her hand on the horse's bridle.

"Mount this instant," she said. "Ride straight home and pray you'll be there in time before the door slams in your face!"

Nina gasped with surprise.

"What d'you mean?" she cried. "Where's Saxon?"

"Locked in the cellar."

The girl turned white with passion.

"How dare you?" she cried, stamping with rage. "Give me the key this instant. You've been drinking! I tell you we're to be married this morning."

"That'll you'll never be!"

"Why, what's he to you?"

"Ask yourself that!"

Girl and woman—they faced each other—a pair of combatants in the grey November fog. Then Nina spoke slowly.

"Oh, how I hate you! I've never hated any woman so much in my life."

The woman winced sharply, as if struck.

"My girl—that's what a kid thinks when its mammy stops it from playing with fire."

There was a sudden softening of the coarse voice.

"Look at me!" she suddenly commanded.

Nina gazed at the handsome, dissipated face, with loathing. She marked the puffy bags under the violet eyes and the red stain of the face, inflamed by spirits.

The woman noticed the shudder.

"Ah, you don't like it? And you didn't like my house. I tell you, even as I and mine are, so will be you and yours! Have you one useful gift to make you fit to be a poor man's mate? Heaven help you, if not. For you're marrying a man who's not in love with you!"

"He is. I tell you, he is!"

The girl's voice rang out, half in defiance, half in appeal.

"He's not. Meet the truth, girl, and don't shy! If I were of equal birth with you"—the woman smiled a crooked smile—"and I beckoned him away from you, which of us would he choose?"

For some minutes Lady Nina stood thinking. It was the blackest second of her young life, when she faced things squarely. Then, with hanging head, she turned towards her horse. It was her answer.

She rode slowly away, while the woman watched her in silence. Before the mist had swallowed her up she returned Hushed and panting.

"I was thinking," she said, "of what you said about closed doors. I'm afraid of my father. Will he hear of this? There may be a scandal if it leaks out."

The woman laughed grimly.

"Don't fret," she said. "Someone'll pay the piper, but it won't be you. You're up against me, and my reputation's good to knock you out of the running. Saxon's visit will be put down to me. The fun's begun already. My old man heard him in the cellar, and they're at each other, hammer and tongs. We'll have a free-fight, directly, but Saxon has a cousin who will nurse him up, and I'll give as good as I get. But you'll be out of it."

Well out of it. With a shudder of disgust, Lady Nina saw the sordid scene.

"I'll go back and tell your husband," she cried. "I can't let you pay for me. I'll stand my corner."

But the woman's rough hand tightened on her wrist.

"Go home!" she shouted. "All your talking wouldn't do a ha'porth of good. Besides, maybe, I've not done all this for you. Perhaps, it's done for the sake of an old grey house, down in a southern country a house that's big enough to hold this village. It's a house like the one you and yours have lived in for generations. Remember that house always! And remember, too, that you've been entered in a race for posterity, where each rider cuts off with a fine, unsullied name, and sees it safely handed down to the next starter, when his course is run. Just now, my girl, you jibbed. You're headed straight again. Keep the track, and Heaven keep you from the cropper others have come!"

Then the woman's voice suddenly changed. Its coarse accent fell away, like an old garment, leaving it bare as at the birth of speech.

"Besides, it doesn't pay," she said, in the new voice. "Remember, if we fall in the race, though we win, the hoof-slide is scarred on the course! And few of us win through!"

Lady Nina blinked away the tears that started to her eyes, for she knew she was face to face with one of the "lost legion."

"Oh, you poor soul!" she cried, as she stopped to kiss the handsome, drink-marred face.

It was a very crest-fallen colt that meekly returned to stables, after three hours of liberty. Lady Nina returned from her ride alone, a trifle pale and subdued, and entirely bereft of her usual swagger. She accepted Lord Townley's proposal to go for a spin in the car with alacrity, and came back in it, formally engaged, to her own, and her family's pleasure.

The duke, in particular, unbent, to express his delight.

"The fact of the matter, Nina," he explained confidentially, "I have been worried on your behalf, because of a certain strain—ahem! Your mother, now; you've been told she died at your birth. In reality, as all the country knows, but has forgotten, I hope, she eloped with a groom in my employ when you were two years old. Of course I divorced her immediately. I can tell you no more of her, but you know where such marriages lead—to the down-grade!"

Nina opened her eyes yet wider. Pity in a vague kind of way for the unknown parent filled them, also surprise. But the duke, who was searching her face with anxious eyes, to his relief saw no light of comprehension dawn there. Her father's anxiety to leave the district and the dissipated hostess of the "Royal George" were two isolated facts—not to be connected with a back-page of stale history to a glare of ugly significance.

When they breathed on the mirror of her mind, and thereby dulled her wits—the gods were kind.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.