RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"IF you could have seen her," said the little man.

Sark swung back his chair impatiently.

"It passes my understanding," he remarked, "how a man of your intellect can waste his time over a woman who has nothing lo recommend her but physical proportion, allied to a certain amount of driving power."

Hare paid no heed to the words.

"If you could have seen her," he said, "when she was playing golf, just now. The sun shone on her hair, and her scarlet skirt fluttered against the green. She—she's a beautiful picture."

"A beautiful cinematograph," corrected Sark, savagely. "Can't the woman ever keep still?"

He continued to frown, as he noticed the pained lines, settling like a flock of vultures, round his friend's mouth, for the affection between the strangely matched pair was deep-seated. A confirmed celibate himself, he had viewed his friend's infatuation with keen annoyance, which changed to contemptuous amusement, as Hare's persistent attentions received but a cool reception at the hands of Miss Evangeline Pope. She was the very latest thing in physical culture, as expressed in five feet eleven of splendid flesh and blood, embellished by a wealth of corn-coloured hair, and clothed by Burberry. When she competed for the golf championship of the north, Fate had landed her at Sark House as the guest of Mrs. Kent, Sark's widowed sister.

Hare resumed his tale.

"I tried to play golf this morning. Thought, perhaps, it would please her. I made a shocking mess of the ground, and a thorough-paced exhibition of myself. Sark, tell me, how can I win her good opinion?"

Sark chuckled sardonically. "Do nothing of the kind. With a purely elemental woman of her type, there is but one method to adopt and that is the method of the Stone Age. Club her, or, in other words, let her see that you are master."

Hare flushed at the derisive words, while his lips twisted to the semblance of a smile.

"You force me to the humiliating confession," he said, "that if I were to try conclusions with Miss Pope, my only chance would lie in ju-jitsu, which would be hardly cricket." Then he suddenly dropped his strained banter, and groaned aloud. "Why am I blasted with this vile, undersized body? A man! I am a mannikin. You haven't heard Evangeline's latest, by the way. I am not supposed to know. She refers to me as—the Microbe."

The grim amusement faded from Sark's face. "She paid you a compliment when she called you a microbe, old man," he said, gently, "for she attributed to you the germ of unlimited power. As for games, if you cannot play yourself, you have taught hundreds of wretched youngsters the way."

Hare's face lightened slightly at the allusion to the Homes which the large heart, cased in his boyish frame, had urged him to provide for many a forlorn gutter-snipe; and it brightened as Sark continued, "I see, I shall have to play the part of maiden aunt on your account, Arthur. To-morrow, when you and I explore the caves in my wonderful mountain, I shall have to depart from the habits of a lifetime, and include her in the party."

As Hare stammered out his thanks, a girl's shrill whistle was heard in the garden below. Hare pricked up his ears at the sound; and, immediately after, a scuttle of feet, a violent draught, and a loud bang of the door proclaimed the passing of Arthur.

Left alone, Sark crossed to the window, and gazed at the distant mountain, which rose in an indigo barrier against the sunset sky. He was a tall, gaunt man, with a massive brow and prominent light-blue eyes. A puzzle to the world in general, by reason of his retirement and eccentricity, since the time he had baffled the medical world by remaining in a trance for eight days, apparently he was a puzzle to himself. His strange eyes, roving restlessly in his impassive face, seemed to be constantly searching for the solution of the mystery of those lost days, in which his Ego had lain submerged. His rugged face softened as he murmured, "Poor old Arthur. Quite hopeless."

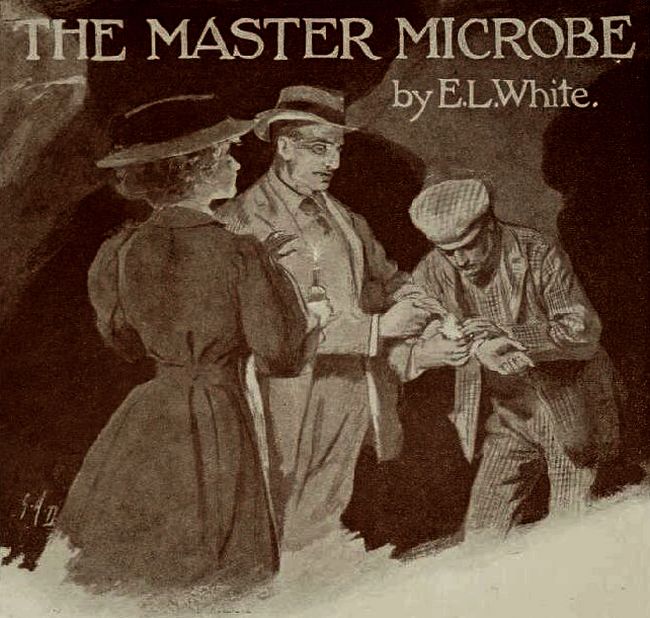

Ten o'clock next morning found Sark, Hare, and the girl half-way up the mountain, bound for the caves. They were a silent party, for the girl, visibly annoyed by the presence of the Microbe, pointedly addressed her remarks to Sark, who proved unresponsive.

After a bard scramble through heather and bracken, at last they emerged on the stony mountain-side. Half an hour later, they stopped, hot and breathless, before a wall of rock. Sark led them to a split in the side, which widened to a steep shaft. As they gazed down the tunnel, a damp, earthy smell rushed up to meet them, like a whiff from a vault. Lighting candles, Sark swung himself into the hole, and the others followed.

It was a stiff scramble, but Hare's timid offer of help was scornfully rejected by the golf champion.

"You'll find it difficult to keep your feet, yourself," she remarked.

But, as she spoke, a stone rolled under her heel, and she pitched heavily forward. Sark managed to catch her before she reached the bottom, but the force of the shock caused him to stagger backwards, till he collided violently with the opposite wall.

"You must kindly refrain from flinging yourself at my head in future," he remarked, as he picked himself up, "even as a proof of feminine independence, although I admit there is a great deal of force behind your argument."

The caustic note in his voice testified to his annoyance, and he abruptly led the way down the tunnel. The apology on Evangeline's lips melted into an exclamation of wonder as the tunnel turned into a passage, which instantly led into another, and yet another, in bewildering repetition. The bulging sides, low walls, floor and roof were all of a curious chalky whiteness.

Hare turned to his companion. "Is it natural?" he asked. "And are you leading us round and round?"

Sark stopped in his walk. "Part of each," he said. "The whole mountain is honeycombed with these natural passages, but they have been cut and intersected with the workings of old quarries. I'm taking you to the great central cave; and if you don't wish to be put very effectually in pawn, stick close to me."

As he spoke, he retraced his steps, and dived into a cutting a couple of yards lower down the passage.

"I took the wrong turning there," he remarked. "That comes of talking."

"Hut where is the chart?" asked the girl. "You cant possibly remember your way without one."

Sark rapped his massive forehead. "It's here," he said, with a chuckle. "No other man in the country could tap this route except by chance. Only the wild foxes and I. It's there. I never forget. Once anything gets into my memory-box, there it stops. Nothing escapes. Except those eight days," he added, in a different voice.

Hare started. It was the first time he had heard Sark allude to his illness.

Then, suddenly, a low, humming murmur began to fill the passages with a hollow boom, as of a monstrous wave flooding each chamber of the honeycombed mountain with sound, and sucking back again, dragging a sullen echo in its train.

"Thunder," said Sark, shortly.

Hare glanced at Evangeline. The strange silence of this white tube, the face of Sark that glimmered weirdly in the dim light of the candle, and then the clamour of the subterranean artillery, were all getting on his nerves. He had the uncanny feeling of being entrapped in a vast, endless burrow, and he longed to rush back again to the open air. But the girl needed no sympathy.

"Lucky we're under cover," she remarked.

Again the trio plodded on their way, Sark picking out the track with apparent caprice through the labyrinth of winding cuttings, while the thunder growled round them, like an imprisoned beast of prey. At every step. Hare's distaste increased.

Presently, the tunnel, which had been so low as to enforce the necessity of crouching, widened and rose to massive proportions. Higher and yet higher the roof reared itself, and with a cry of wonder they found that they were on the threshold of a vast stalactite cave.

Dimly seen in the flickering light of the candle, at first it only suggested majesty and mystery. But through a crack in the central dome, suddenly, a vivid flash of lightning bathed the interior in a violet glow, and instantly they had a vision of white fluted pillars fading away in the distance, like a forest of pines. Then, as a terrific bellow of thunder was belched out of the leathern lungs of the Storm Fiend, the cave shrank hack again to a glimmering spectacle of spectral column and arch.

The girl cried out in wonder at the sight; but Hare did not heed her words, for he was gazing at Sark in some alarm. In the vivid glare of the lightning, his friend's features appeared unusually white and tired, while the eyes glowed feverishly in the drawn face.

"Good Heavens, man!" he exclaimed. "What have you done to your wrist?"

Sark raised his hand languidly, and displayed the ugly, gaping mouth of a crimson cut.

"I must have grazed myself when Evangeline bowled me over," he said. "I thought something felt uncomfortable, but I did not take the trouble to locate it. It's no matter."

"Of course not." Hare's voice was sharp; but, when he bound up the wound with his handkerchief, his touch was as gentle as a woman's, while the girl looked on uncomfortably, like a ministering angel ousted through foreign competition.

"I'm awfully sorry," she said. "Now, don't you think we had better explore?"

"I don't go a step until I have had lunch." replied Hare, fumbling with the straps of the basket.

The girl's lip curled. Her chief complaint against the Microbe, in addition to his inconvenient devotion, was the very short measure that Nature had allowed for his manufacture. Now, by his indifference to this natural miracle, he was giving indication of being also made of shoddy material.

Yet, when the basket was unpacked, and her wants supplied, Hare only waited to see the imprisoned sunshine of the South make golden bubbles in Sark's glass. Then he stole away, bent on an exploration of the cavern, his keen features lighting with pleasure as he discovered each fresh marvel of the formation of the stalactites.

He wandered farther away from the group, thoroughly absorbed in his occupation, and heedless of the intermittent growling of the thunder and the steady drip of falling water. Suddenly, the cave was rent by a shriek. Turning hastily. Hare ran in the direction of the sound, a premonition of horror chilling his heart.

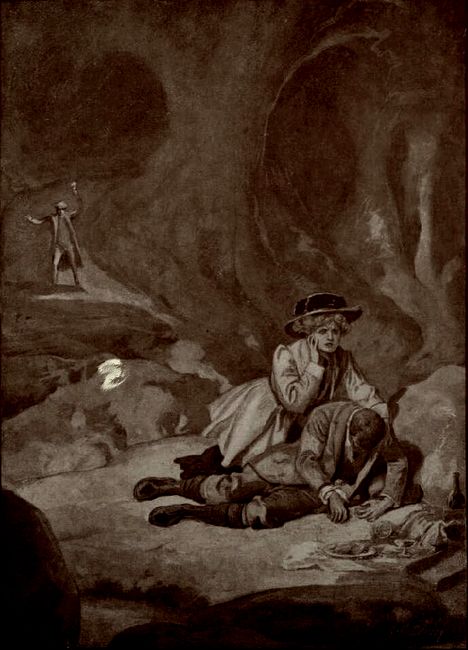

Before he reached his companions, the lightning flickered on the group, and he saw that Evangeline was on her knees, shaking the limp form of Sark. In the sudden glare, his friend's face took on the yellowed look of a wax-work. The ridge of his nose rose like a hook, and his chin dropped in a horrible wobble.

Evangeline was on her knees, shaking the limp form of Sark

Evangeline looked at him in horror. "What is it?" she cried. "He turned like that quite suddenly."

Hare's voice shook. "He's worried me the whole morning," he replied. "He's been seedy all the week, and the stiff climb, the thunder, and the loss of blood have bowled him over. I thought the champagne would put him right."

"Is he dead?" asked Evangeline, in a Frightened whisper.

Hare, busy over the prostrate figure, made no answer. He felt the pulse, gazed into the glassy eye, and finally, dragging it to a recumbent position, he wrapped his great-coat round the stiff form. Then, at length, he spoke—his voice panting with his exertions.

"No; he's not dead, thank Heaven," he said. "You remember hearing of his strange attack, three years ago, after influenza. Well, I don't want to alarm you, but I'm afraid that another—in short, he is in a trance."

In the sudden relief, the girl spoke flippantly.

"Well, I must say, he's chosen an inconvenient time to have one. I had better contribute my cape as well, to keep him warm. When will be wake up?"

Hare moistened his dry lips, full of pity for the unconscious girl. "It may be fairly soon. Of course, we have no reason to expect otherwise." Then he added, quietly: "The other one lasted eight days."

"Eight days!" The first premonition of alarm flickered in the girl's eyes. "Then we must leave him here, and send someone to fetch him home. Ugh! How ghastly he looks! Like a corpse. Come away from this place. It is dreadful. Hurry!"

From the half-hysterical note in her voice, Hare knew that the dreadful truth which was sucking the vitality from his brain with its octopus-like pressure had now flicked across its first tentacle to the girl, who strove desperately to ignore its existence.

Hut he realised that subterfuge would not avail them.

"My dear girl," he said, simply, "I can't tell you how sorry I feel for you, but you must be brave and face things. We don't know the way out."

For a minute, the girl sat in rigid silence, as though from some recess in the pillared heights she had caught a glimpse of the Gorgon's head. For the first time, the splendid tide of youth and Strength that coursed through her veins had beaten against a rock. Something stood in her way—something dark and terrible, that she dared not mention, lest it should suddenly spring at her when it heard its name.

Death.

Then she jumped to her feet. As Sark had remarked, she was an elemental creature: and, child-like, she strove to dissipate her terror by venting her rage on the first unoffending person. She turned to Hare. "Do something," she commanded. "Don't sit there. Do something!"

"I must think first," he answered.

She stamped her foot. "Oh. if only I had a man with me." she cried.

The insult, which at another time would have filled Hare with helpless rage, failed to reach him, for he had gone down to the depths, whence the bitterest words lack weight to sink. He felt that some fiend had presented him with the pieces of a diabolical puzzle, and the pieces were joining together with relentless rapidity. The impossibility of rescue, since no one had known of the goal of their destination, and the absence of design in the haphazard labyrinth, the clue of which lay in the frozen shell of Sark's head, dovetailed into their inevitable fate. In imagination he already beard the pattering of rats' feet. Then he realised that his companion was speaking to him.

"If you have done your thinking, perhaps you will do something," she suggested. "Take one of those candles, and see if you can find a way out."

Hare sprang up with alacrity. "You won't be afraid to be left?" he asked.

She smiled acidly. "Of course, if you really want company I will come," she said. "Otherwise, I can dispense with your—er—protection."

Her tall form towered over the little man, but he barely heard the words. Leaving the dim vault behind him, he plunged into the first of the low white warrens, carefully noting his route for future reference. The passage corkscrewed immediately, and a sudden sense of loneliness fell on him like a shower of blight. As the sound of his footsteps echoed weirdly down the passage, it seemed as if the crusted silence protested against the sacrilege of being thus broken. He carefully searched the ceiling, the walls, and the floor for some familiar feature, but the blank whitish surface only dazzled his eyes with its monotony, and he groaned at the hopelessness of his task.

The passage suddenly forked in two. Hare stopped to consider. Then he raised his candle, on the faint chance that the flicker might betray a current of air. To his surprise, the blue flame slightly wavered, and he struck out towards the left, with a sudden hope spurring on his steps. The idea was so simple that he cursed his benumbed brain for not having thought of it before. The air was not unpleasant in the tunnel, and by following the draught he was bound to reach an outlet.

He almost ran down the passage to the next cutting, and this time the flame shot out perceptibly towards the left. Hare's heart leaped within him as he pressed on. The maze soon began to thicken, and at every second yard a fresh route had to be chosen, but, in spite of the detours, he knew that he was steadily pressing in the one direction.

Suddenly, the man gave a shout of delight, for a rough projection of plaster in the form of a rude Maltese cross had caught his eye, and he remembered distinctly passing it in company with Sark. He turned round, and raced down a long corridor, his shadow leading the way. A faint bluish light had crept round the corner in front, that fought the candle's rays with its cold intensity, and the man hailed the blessed daylight with a glad shout. He rushed round the corner, his heart pumping with excitement, and then he stopped short in dismay. Before him stretched the great central vault, with the daylight struggling in through the gash in the centre. With a revulsion of feeling, he realised that he had been walking in a circle.

He looked round the desolate place with a feeling of mad hatred. Beneath the great dome, the cloaked figure of Sark lay in its rigid sleep, but the shadows had wiped out the lest of the scene with its sooty fingers. At last he spied the girl's form in the twilight, her knees drawn up to her chin, and her eyes tightly closed. It seemed to Hare that she no longer looked tailor-made, but merely a bundle of clothes.

When she had been left alone, the utter loneliness of the spot had soaked her through and through. The horror of the position no longer stalked her warily, but, coming out into the open, had boldly swooped down on her as its prey. It seemed to her that the great white pillars had wavered into life, and advanced towards her in a measured march. When she saw the peaky face of Hare, looking more pinched than ever under its jaunty tweed cap, she hailed the little man with a sense of unaccustomed relief.

"I must get out." she cried, shaking Hare's arm convulsively; "I must. I shall go mad if I don't, I tell you. It's terrible—terrible!"

Hare realised with a fresh feeling of horror that she was on the verge of violent hysterics. He knew the theoretical treatment of such patients, but the little man's dread of Evangeline was stronger than any other feeling. As he glanced at Sark's stiff figure for inspiration, in imagination he could see his friend grappling with the situation with careless scorn.

"Let her see you are master. It is the only way to treat an elemental creature like that." He recalled the words, but was only conscious of an overwhelming desire for flight.

A long, sobbing breath from Evangeline warned him that action was imminent. Then, with a shock of surprise, he realised that a thin, metallic voice, that he failed to recognise for his own, was speaking.

"My good girl, don't begin to cry! If a woman only realised what a spectacle she presents when she weeps, she would refrain from such a daring experiment."

The girl's sensibilities were already passing beyond her control; but feminine Vanity, the last to desert the human frame, caught the words. With a sudden shock, she came back to earth.

"I wasn't going to cry," she said in an injured voice.

But Hare did not hear her words, for he was transported out of his present sense of peril by an overwhelming breath of triumph.

"I have done it," he told himself. "I have actually done it."

His success went to his brain, making the little man reckless. He longed to test his newly gained power further.

"Sit down," he commanded sternly, "and finish your lunch. It is strange how few people realise that dying is quite an easy affair, simply the effort of a minute, as opposed to the long strain of living decently. Particularly for a chap like me, with a properly developed brain in a mis-fit body, who has, in consequence, to be the butt for idiots all his life. You will be better after lunch."

Evangeline protested faintly against the aspersion that her courage was of the purely animal kind that has to be sustained by chicken and champagne; but her remonstrances were stamped out by the transformed Hare.

But as he watched her, as she ate her food in a dazed manner, his wild spirits gave way to sudden depression. What was the good of her altered attitude, that had been the instant consequence of his acceptance of Sark's advice? The feeling of freedom and mastery that had bubbled through his veins like strong wine, now began to leak steadily away as the remembrance of their plight came back to him. The girl watched his face curiously.

"What are you thinking of?" she asked.

Hare smiled. Two hours previously, Evangeline had not credited him with possessing the ordinary feelings of a man. Now she was not only endowing him with intellectual mechanism, but was manifesting an interest in its working. So his answer came from the depths of a full heart.

'"I was thinking what a pity it is!"

Her eyes brimmed with tears.

"Isn't it?" she cried. "Isn't it dreadfully hard? Think! I have everything—youth, strength, good looks, lots of friends, the championships, everything. The world was at my feet, and now—"

As her voice failed from emotion, Hare's prim tones broke in.

"I wasn't thinking of you," he observed. "I was thinking of myself."

"You!" All the old scorn of the physically perfect woman for the undeveloped Microbe was breathed in her voice.

"Certainly," returned Hare, his militant instincts uppermost. "Your loss will be a purely sentimental one. A splash at first, and next year, your partners will be sitting out with other women, while they speak of you as 'that poor girl.'"

She wriggled at his words. "And how will the world feel your loss?" she enquired haughtily. "As a valuable ornament gone—like the Venus' arms?"

"Don't you think that tone is a little out of place at this present moment? If you really wish to know, eight hundred poor little atoms will miss me. A large portion of my worldly goods goes annually in keeping up the Homes, but—ass that I was I omitted to put the thing on a sound financial basis. They should have been permanently endowed. Oh, fool, fool!"

He had forgotten her presence, and she stared at him in wonder. She had beard Sark allude to his wealth, and the very riches seemed to stamp him with vulgarity. Now, as she thought that this slight man, with the brooding eyes, controlled the destinies of hundreds of little human beings, she felt suddenly cheapened.

A long silence fell on the pair. Presently the girl began to shiver, and Hare crossed over to Sark's cloaked form, and picked up the girl's golf cape.

"You'll want this yourself," he said, tossing the wrap over to her.

But she came by his side, and stood looking down at the frozen form.

"Just to think it is there, inside him." she cried. "The secret that we're longing to get at. I wish I had a galvanic battery, and could make him speak for a minute!"

Hare took no notice of the girl. As his eyes roved over the corpse-like figure of his friend, noting the limp hands, the purple mounds under his yellowish eyelids, and the bony framework of his face, his brains suddenly felt as fresh as though newly pared. He turned to the girl.

"He has spoken," he said quietly. "I believe I have the clue."

Evangeline started back in sudden fright, terrified lest the little man's brain should have given way under the strain.

"What do you mean? Speak! Shall we get out? Shall we get out? Speak! What do you mean? I never heard him. But you have a clue? Oh—"

"If you don't stop chattering this instant, you may stop here forever," said Hare sternly. "I have a clue, but it takes some working out. Sit still, and not another word, until I speak to you."

She opened her mouth to remonstrate. But she closed it again; and, flopping down on the nearest stone, she fixed her eyes on the little man opposite. Then the silence in the cave was only broken by the long-drawn puffs of Hare's pipe. In almost reverential wonder for the workings of the brain, the girl watched the finely cut face start out of the shadow, in the light from the glowing bowl. There were concentrated lines of thought on his brow, and his eyes were groping in the realms of theory.

Presently, he got up, and walked up to Sark's body. He bent over it for a few minutes, then crossed the cave, and groped about near the outlet. Dropping to his knees, he writhed about, shooting out his head like a tortoise. Then, with a cry of triumph, he swooped down on something. The next instant, he sprang to his feet, and darted out of the cave.

Jelly tore after him.

"Don't leave me," she walled. "I never spoke. Don't leave me!"

The thrill in her voice tore at Hare's heart-strings. He longed to turn and vow that neither life nor death could ever part them, but his instinct warned him to refrain.

"I will be back in a minute," he said condescendingly. "Be a good girl till then."

So the famous golf champion again subsided on a stone to await the Microbe's return. Ten long minutes crawled away, and then at last, he reappeared. His face was flushed, and there was the nearest approach to a swagger in his walk.

"Pack up, and let's be moving." he said. "The sooner we can bring help to poor old Sark, the better."

The girl clasped her hands. "You have discovered the way?" she breathed. "It is like magic. I never thought anyone could he so clever."

Hare smiled. "Your first lucid remark, a little time ago," he observed, "was a regret that you were not imprisoned in company with a man. As a matter-of-fact, you can congratulate yourself that you were not shut up with a rudimentary intelligence, backed up by so many pounds of brawn and muscle."

"I owe you everything, and I know it," she answered.

"Do you find the debt irksome? If so, we will cry quits directly."

"No," she said softly, "I think—I think I like to owe it to you."

Out of the dread white cavern they passed. As they bore away the candles, the awful pillars faded away to darkness.

Hare stepped ahead briskly, for the first few hundreds yards of the endless passages, taking the turnings with confidence, But as they proceeded farther on the way, he slackened his pace, and went along slowly, holding his candle first above his head, and then to the floor. Several times, he crawled on his hands and knees, his nose almost scraping the ground. Once he left her alone, while he dived in turn down several intersecting passages.

With breathless interest, and full of blind faith, the girl followed every movement. Only once did she dare to speak.

"Is the clue all right?" she asked.

"Splendid," beamed Hare. "It's slow work, but when we least expect it, we shall find ourselves outside."

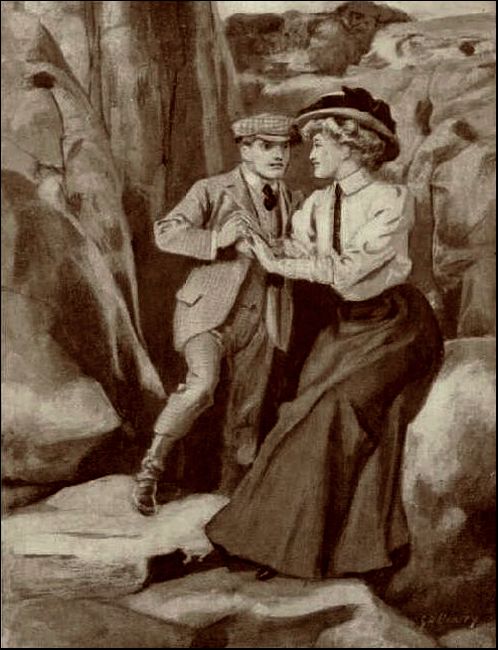

That was what actually happened. In three minutes, the endless whitish walls darkened into rock, and the passage widened abruptly. Then round the bend, formed in black stone, and its edges serrated by a fringe of ferns, glimmered a patch of the blessed blue sky.

With a cry both ran forward to clamber up the steep ascent. As a matter of fact, it was Evangeline who dragged up Hare; but neither was conscious of the fact. For both stood out on the mountain side, with a freshly washed world lying green and glistening at their feet, while great white clouds flapped with a tremendous swirl, as of white linen, against the blue drying-ground of the sky.

The grass was whitewashed with daisies, and the strong breeze blew into their pale faces and filled their lungs with great draughts of oxygen. Hand in hand, they gazed on the scene, as if they saw a new world.

Hand in hand, they gazed as if they saw a new world.

Then the golf champion spoke. "Isn't it beautiful!" she cried. "You have given it back to me. Tell me, how did you find the way?"

But Hare shook his head. He felt it would spoil their beautiful romance to tell her how his glance had fallen on the bandage on Sark's hand. Of how his brain had seized on the possibility that the slowly-forming drops of blood must have ebbed from the wound at intervals. Of how, with infinite difficulty, he had traced back that faint trail of blood that Sark himself had laid. It seemed cheap and commonplace, compared with the miracle of the other trail he had followed, at Sark's instigation, that had led through the outer barrier of rocks and briars, right to the sanctuary of Evangeline's heart.

So he—the most obvious of men—was actually guilty of the impropriety of a double-entendre, as he answered evasively, "Oh! From something Sark let drop."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.