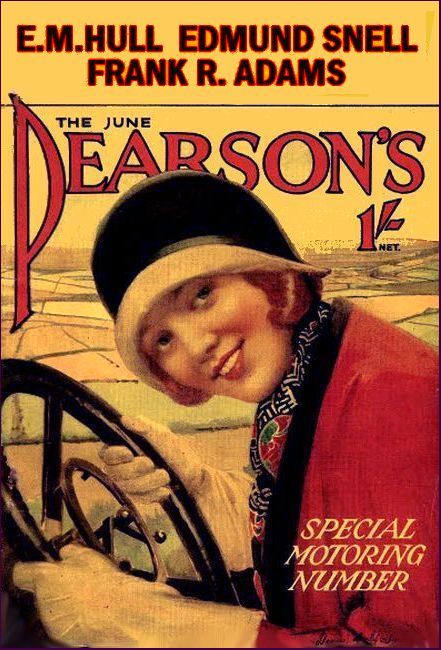

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Pearson's, June 1925, with "The Pillow"

LITTLE Ginger lay in bed, crippled with muscular rheumatism. She was racked with pain whenever she stirred a finger. She was entirely dependent upon the grudged services of her step-mother, Jitta. And she hated Jitta. But she kept on smiling. For inside her pillow was £380. Jitta was 10 years older than Ginger. She was an ice-cold brunette, with snapping black almond eyes and thin scarlet lips. All she cared for was money.

She had made a precious bad speculation in her marriage to Dan Scudamore. He was the son of a gentleman-farmer, but the family was going downhill. Since Jitta had spent his modest patrimony, Dan had been selling goods on commission. Like his daughter, he was a Rufus. He was a big man, with a red, clean-shaven face and jovial blue eyes. His was the type which went with prosperity—sporting clothes, dogs, and money to 'jingle.'

He put up a brave bluff at the confidence which spells success in business. But while he fixed customers with magnetic blue eyes, they held apology. He told broad stories to men, but his loud laughter could not hide the tremor of his lips. He had reached the stage when he had to goad himself to make his daily round of humiliation and failure. He had to force his way into houses where he was not welcome, and pester people to buy goods which they did not need.

Dan was a gentleman, and he hated making a nuisance of himself. When he made a sale, he felt that it was the result of pity.

And he hated pity.

He got none from his wife—Jitta. She had him well to heel. She lashed him with her tongue. Worse than all, she had taught him to despise himself.

For this last, Ginger hated her.

Yet, although Ginger had the fiery temper which accompanies red hair, she dared not quarrel. While she lay there Jitta had the whip hand.

Jitta resented the extra work of her illness. She did the minimum for the invalid. Thrice daily, she slammed down a tray by her bedside. It was left to Dan to wash Ginger's face and make her bed. Still, that was to the good, for it enabled them to preserve the secret of the pillow. It was only the knowledge of that £380 which kept Dan going in his little hell of life with Jitta. It was the key to release.

Formerly, it had been, placed on deposit But Dan's nerve crashed upon the failure of a certain bank, popular with small investors. He withdrew the whole, in twenty-pound notes, and the bulky envelope, was sewn up in Ginger's pillow.

The hoard was the slow growth of years—the salvage of Dan's War Gratuity, and Ginger's savings.

Before her illness, Ginger—who had taken the first job which offered—had been a waitress at a celebrated London restaurant. Quick as a needle to adapt herself to town surroundings, within a month, she had covered her freckles with powder and used a discreet lipstick. She was smart as paint, from every live red hair to the silk stockings which twinkled under her knee-short skirt. She soon became popular with the clientele of the restaurant, for she nipped round and executed an order while another girl was writing it down. For every sixpence the other waitresses took up. Ginger picked up a shilling. They all went into the pillow.

For six weeks now, Ginger had lain in her lumpy bed, suffering the torments of inactivity and baffled rage. She was denied even the solace of privacy, for Jitta kept the overflow of her wardrobe in her room. She dared not rebel. Jitta had ways of getting even with, her. She had known what it was to lie parched for hours, while Jitta gossiped at the gate. And Jitta never gossiped with women.

Ginger gritted her teeth, like some small trapped creature, as the door was kicked open and Jitta entered her room. Taking no notice of Ginger, she walked to the window and stood there, polishing her nails upon a dirty pad. Although it was early in the morning, she was dressed in a short tight skirt of large plaid: her orange silk jumper left her big arms bare to the shoulder. Round her neck was a string of enormous imitation pearls.

Ginger knew that downstairs the dirty, dishes were still unstacked, so that Dan would have to wash his own plate when be returned. A film of dust covered the carpet. Under the bed, the fluff was piling up in drifts. Ginger began to boil.

"When I get about again," she said, addressing the air, "I'll soon have the place shipshape and Bristol fashion."

Jitta regarded her with callous eyes.

In her London days Ginger had rather resembled a pretty little red fox. Now—with her tangle of matted hair—she looked more like a lost sandy kitten, with an unwashed face.

Jitta ran her fingers over her over shingled head, which gleamed like black lacquer.

"Best begin on yourself," she remarked scornfully. "Sly! You do look a sketch."

"I can't help it," gulped Ginger. "Lying here, not able to do a stroke for myself."

"Got others to do it for you, haven't you?"

As she spoke Jitta banged open a drawer and shook a new nightdress from its crease. It was sleeveless and made of lemon crÍpe de chine.

Ginger watched while Jitta packed it inside a suitcase, to which a luggage tag was already tied. Her sharp eyes read the name of a celebrated Brighton hotel. Her grey-green eyes grew bigger. She knew that Jitta was indifferent to scandal, but she had never before gone openly away for a weekend. Yet whatever she did, Ginger knew that Dan would take it like a lamb, lying down. There lay the sting. Yet safer so. She always remembered their bull terrier who had bitten the postman.

Dan explained the attack to the board, "He's mild as milk and he stood this man's tormenting, day after day—week in, week out—till he reached a point when he couldn't stand any more."

The Bench—doggy men all—had spared the bull terrier's life. But Ginger never forgot. She knew the time would come when Dan's patience, too, would break. That day he would see red. He hated Jitta, but he did not know it. Ginger knew. And this fear was always in her mind.

Jitta snapped the suitcase and slouched into her own room. She returned with armfuls of clothing of all kinds—suits; frocks, jumpers—which she flung on the bed.

A sudden flicker of mad hope shot through Ginger.

She crushed it resolutely. Such a wonderful thing could not happen. It was too good to be true.

At last she could restrain her curiosity no longer.

'Whatever are you up to now, Jitta?

"Selling my old rags."

"Are you expecting Mrs. Pomeroy?"

Jitta deigned no reply. She rubbed her nails to higher polish. Presently she went downstairs and Ginger heard the owning of the front door.

The wardrobe dealer's big laugh floated up the stairs. When, she entered the bedroom with Jitta she brought with her a sense of warmth and life. She was a handsome, portly matron of 50, with a rose-red colour and fine dark eyes. She wore a long seal coat and carried two enormous Japanese handbags. She spoke to Ginger with real kindliness.

"My! Ginger in bed! What's the matter?"

"Screws," said Jitta indifferently.

"You don't say so!"

Mrs. Pomeroy clicked her sympathy. "Dear, dear! When my old man gets lumbago I iron his back. Have you tried that?"

Jitta laughed scornfully. "No fear! Me? I'd like to know why she didn't go to a hospital in London, instead of coming here to be nursed. You'd think this family came from Aberdeen."

"Now, my dear, that's not the way to talk," purred Mrs. Pomeroy. She betrayed no sighs of professional interest, although Jitta was adding to the piles on the bed. Presently she dumped down a final bundle, and stood, her hands on her hips.

"That's the lot. Make a bid, Mrs. Pom."

Ginger's eyes, grew bigger as the flame of hope shot up again. Something vital was in the wind. Mrs. Pomeroy did not glance at the array of finery. She strolled nonchalantly across to the door and fingered a near fur coat which was slung on a hanger.

"I'll give you a pound for that coat," she said.

Ginger's face flamed. "It's mine. Jitta sold it to me for four pounds."

"In instalments," snapped Jitta. "'Tisnt yours till the last is paid."

"Well, before you sell it you'll, have to give me back the two pounds I've paid you, won't she, Mrs. Pom?"

Mrs. Pomeroy, however, had made her gesture. She turned her back on the coat, with a shrug, and allowed herself to become aware of the clothing on the bed. She took up a skirt and held it up to the light. Ginger noticed how all the geniality had drained from her face. Her eyes glittered like black glass as she disparaged one article after another.

"They're not the fashion. People want a lot for their money, these days, ready-mades being so cheap. The trade's not what it was. No one'll buy an out-of-date cut."

"My lord!" Jitta exploded. "They're the latest." She picked up a vivid checked silk frock. "I got this from Paris—well, never mind how!"

Mrs. Pomeroy threw her a curious glance. She adopted a swift change of tactics.

"Well, now I look at it, I can see it for myself. There's a bit of sauce. Heal style—all of them—and in good condition. But, tell you the truth, I'm overstocked as it is. The Hall's gone into mourning and I took away all their colours yesterday. But I could offer you a good price for underclothing."

"Righto!"

A spot of colour burned in Ginger's face as Jitta opened the lower drawers of the wardrobe and feverishly raked out their contents. "Plenty here. But, I warn you, no lump sum. Every blessed thing is to be sold separate, even if it's only odd pence."

Mrs. Pomeroy grimaced as Jitta produced a slip of paper and pencil. Both women knew that the threepences and sixpences would add up to a higher total than any direct offer.

"You seem to be having a wholesale clearout," she remarked. "You'll want another trousseau to make up. Are you thinking of a second honeymoon?"

Jitta did not respond to her wink. She looked at her under insolent lids.

"I'll tell you one thing. Nothing under a fiver's any good to me. Will you give two shillings for this?"

"Funny, eh? Give you fivepence."

Ginger did not hear her wrangling. Her heart was singing with joy. Like one who had dwelt long in a cellar, she saw the door open to a vista of light.

There was no longer any doubt that Jitta was selling all she possessed. It could mean only one thing. She was going away for good.

Everyone had predicted that the Scudamore marriage would end that way, but Ginger had credited Jitta with too much selfish prudence to burn her boats. She knew that Dan would never take proceedings against her. She had trained him too well. Poor bluff, beaten Dan kept flying the banner of his wife's loyalty as though to salve the pride he had once possessed.

He admitted—speaking with Jitta's voice—that since he was not man enough to provide a smart woman with more than a bare living, he could not grudge her the amusements which other men were able to offer her. It was natural for women to want small presents and visits to the cinema.

But, while he affected to see nothing, Ginger had seen his eyes, blaze like fire between his sandy lashes; she had noticed the involuntary, clenching of his fists.

To-day, her fear would be laid to rest for ever. The end really was in sight. When things had seemed at their blackest the worst had turned to the best.

Ginger turned unwarily on to her back. In the rapture, she scarcely felt the torture of her racked muscles. She did not worry about the ethics or morality; to her, Jitta was merely about to do openly what she had done in secret. And the prisoners would be free.

They had often talked, in secret, of the day when they would sail into the sun and begin the new life of freedom. For that end they had saved, even though the goal was obscured. They had planned to join Ginger's lover in California. He was already working his small prune plantation.

Dan often talked wistfully of a man's life in the open, with aching muscles and plenty of sweat. Ginger, too, had her private, dream of running a restaurant, with home-made fare and black-and-orange checked tablecloths. She suddenly gurgled as she looked at Jitta's tense face. There was rich humour in the situation; while Jitta was scraping together the halfpence, Ginger was lying upon a small fortune.

While she was helpless, it was any one's—for the taking.

"What's Ginger smiling about?" asked Mrs. Pomeroy. It seemed to Ginger that she towered above her bed, like a steamer over a small boat when boarded from the open sea.

"I'm thinking of my boy in California. Summer there? It's nice to think of the sun."

"To be sure. This house always stinks of blue mould."

The mill house was certainly damp, it was responsible for Ginger's rheumatism, but the rent was low. It lay below the level of the road and was built beside the stream which flowed between towering banks. Fallen leaves lay around it in sodden piles and the gorge was choked with the thin blue smoke of mist. Altogether, an ideal place wherein to think of the sun.

"It's not fit for pigs to live in," declared Jitta wrathfully. "But he won't move."

She never referred to Dan by his name.

"If your good man could afford a better house," said Mrs. Pomeroy soothingly, "I am sure be would. But you can't blink facts. The Scudamores have always been noted for their bad luck."

The words fell with a chill on Ginger's heart. It was true. The family was on the down-grade. Nothing good ever came their way. They dreamed—but to wake. She tried to shake off her depression, by picturing Dan's homecoming that evening. She imagined the dawn of incredulous joy in his eyes. They would search the paper for the first sailing; Ginger intended to go on that ship, even if she had to be carried on board. Together, they would open the pillow and recount their hoard.

But it was no good. She had grown vaguely uneasy whenever she thought of the pillow. It seemed like courting bad luck.

Her eyes persisted in following, Mrs. Pomeroy. There was no doubt that she was a terrific personality. She commanded the situation, in spite of Jitta's dominant nature.

She shook her head at every appeal to examine Jitta's discarded wardrobe. "I wouldn't give the thing house room. But I could do with old boots and shoes—or gentlemen's clothes."

Ginger read her expression when Jitta retuned from her room burdened with her entire stock of footgear. If she wanted confirmation of her own suspicion, it was plainly written on Mrs Pomeroy's face as she looked at Jitta. It bore grudged envy for one who had the courage to quit dull domesticity for lurid adventure, blended with the contempt of the respectable matron towards the woman who throws her cap over the windmill.

"Heels run-over. Soles thin as brown paper."

While she haggled over the shoes, she kept throwing appraising glances towards the piles on the bed. They were not lost on Ginger. Jitta had shown her cards. She was obviously desperate for money to buy new finery for her venture. It was Mrs. Pomeroy's cue to ask for anything else that was saleable, so that, at the end, she could obtain the lot for a song.

While she bought the shoes for starvation prices, her wandering eyes made Ginger feel uneasy. This woman was ruthless where her pocket was concerned. Jitta, too, was reckless, and would not care how she despoiled the nest she was leaving for ever. And Ginger could not raise a finger in her defence.

She realized her own helplessness when the women began to laugh at Dan's suit. In striking contrast to Jitta's stock, he had but one to spare—a sporting affair, of shepherd's plaid. It was ancient to the last degree, but poor, shabby Dan always invested his clothes with his own air of breeding. Pockets may be empty, but an unbroken line of yeoman ancestry will tell.

The empty suit looked grotesque and moth-eaten as dangled in Mrs. Pomeroy's clutch.

"About fit for a scarecrow," she sniggered. "A man with a smart wife didn't ought to let himself run to seed."

"I give you my word," broke in Jitta passionately, "that there've been times when that I've pretended not to see him in the street, I've been so ashamed."

Ginger writhed as she listened: her hot blood boiled. Had she been able to rise, she would have flown at them like a little tiger-cat.

"And you fancy a swell dresser, eh?" Mrs. Pomeroy the smiled archly. "Well, there's as good fish, you know. Between you an me and the bed-post, is it true that stripes are the fashion, this season?"

"That so?" Jitta bright yawned ostentatiously in her face.

Ginger swallowed her rage. Temper could do Dan no good, and it only weakened her. In addition, it had given her a terrifying insight into the fury of elemental passion.

But that old fear was stilled. Before Dan came home, Jitta would have gone away with Tiger Morgan—the manager of the local cinema. Ginger had recognised the allusion to his taste in suitings. Her elation, however, had now entirety left her. She felt vaguely worried and apprehensive. Mrs. Pomeroy seemed no longer a genial, well-preserved woman, but a harpy, with avid claws outstretched to by pounce on all and she fancied.

As she watched her, Ginger fell a prey to a terrible fear. They would sell her pillow.

She tried to shake off the morbid fancy. Even the family ill-luck had its limits, she could not conceive a cruelty which had raised them to the heights, only to dash them down in ruin.

She began to pray fervently that the wardrobe woman would leave the house. Her petition was not granted. Mrs. Pomeroy had not bought sufficient to half fill one of her hampers.

Jitta—biting her lip over the low total on her paper—walked desperately towards the bed.

"Have a heart, Mrs. Pom. I tell you, I simply haven't a bean. I never get anything from him. Come on. I'll take a lump sum."

"Right."

Mrs. Pomeroy laughed.

"Ten bob for the lot."

"Ten? Well—I'm—They'd fetch more for rags."

"Try! The rag-and-bone man will be round next week."

Jitta could not wait for him. Mrs. Pomeroy knew that. She smiled, although the fruit had not fallen when she shook the tree.

"I've a party coming to-night," she observed, "that's going to be married—and not too soon, either. Now, what have you got to spare in the household line? Any old carpets?"

Ginger held her breath as Jitta shook her head. It was like the children's game of "hunt the thimble," where the seeker is guided by cries of "hot" and "cold."

"Rugs? Curtains? Tablecloths?" Mrs Pomeroy was still cold. "Counterpanes? Eiderdowns?"

She was growing warm. Warmer.

"Dear me! No old sheets or blankets?"

Ginger could hardly breathe. It was but one step away from her treasure. She waited for the connecting thought which would bridge the gap.

"I'll see what sheets we have," said Jitta. "Making me work, aren't you?"

There was no spare linen at the Mill House. Mrs. Pomeroy turned down the corners of her mouth at the few ragged sheets.

"I can't make you an offer for this tripe. It's past turning sides to middle."

"More shame to him. He's never restocked since we were married," cried Jitta vehemently. "And Ginger's never sent home so much as a duster from the White Sales for all the money she makes."

"Ginger?" Mrs. Pomeroy's ears were pricked. "She can't, earn much."

"Oh, no," Jitta laughed scornfully. "She only takes pounds a week in tips. A girl who works in the same shop told me."

Ginger's face began to burn. She had no idea that Jitta knew of her earnings.

"Look at her blushing," said Mrs Pomeroy. "You mark my words, Ginger's got a stocking."

Ginger felt a real terror as the two women stared at her. As she lay there, a little palpitating heap of nerves, the blow fell.

Mrs. Pomeroy kicked aside the sheets.

"Got any pillows to spare?"

All the colour drained away from Ginger's face.

Jitta admired the polish of her nails.

"M'm. Yes. He always sleeps with two."

The throb of Ginger's heart was the a great engine. It raced and pulsed while Dan's pillow was fetched and examined. Her secret was still safe. But Mrs. Pomeroy was getting nearer every second. She was hot—burning—she was on fire. The pillow was brought in. She scratched her eyebrows in thought.

"Got another to make the pair?"

"Yes. How's this?"

Jitta jerked the pillow from under Ginger's head. Ginger felt the sweat, break out on her pale face. Carelessly Mrs. Pomeroy let £380 slip through her itching palms.

"No. Two small. I want a couple of squares for a baby's cot, but it's too big for that." She jerked her thumb in the direction of Jitta's pile. "I'll give you a pound for that lot." Jitta passed her hands over her polished shingle with a desperate movement.

"Thirty," she cried.

"Twenty-five."

"All right. But it's blood money."

Mrs. Pomeroy packed her hampers swiftly and dexterously.

"I'll take only the one and send a boy for the other this afternoon," she said, straightening herself.

"Don't do that!" said Jitta quickly. "There'll be no one here all day, for Ginger can't move. I'm going your way as far as the Red Lion. I'll take the other hamper and drop it there."

Mrs. Pomeroy opened her purse and took out three notes.

"Here you are. Three pound. But there's an odd fourpence owing to-night. I must have something for it.... This will do. I can use the feathers."

She picked up Ginger's pillow. Ginger choked back her scream. She knew that her only hope lay in silence. If she could only keep cool and not arouse suspicion, Dan would be able to get back the pillow from Mrs. Pomeroy that same evening. It was torture to lie still while Jitta dressed herself for her final departure. At last she came back to the room. Without a farewell glance at Ginger, she took up one of the hampers by its strap. Mrs. Pomeroy stopped her.

"No. Leave me that one. It's got the small pillow. It's just struck me that I've a party coming at four, about the baby's cot. There'll just be time to rip open the pillow and fill a couple of small squares."

"No! No!" Ginger's lips moved soundlessly. She tried to rise, but the room turned black. She fell back in a faint. Neither woman noticed her. Both had paused by the door, on which was the fur coat.

There was a rapid interchange of glances.

"Two pounds," breathed Mrs. Pomeroy. As Jitta nodded, she whisked the coat from its hanger.

"Best not let it be seen," whispered Jitta. "People know I sold it to her."

"Trust me. I'll sell it outside the neighbourhood."

Mrs. Pomeroy plumped noiselessly to her knees, and unstrapped a hamper. "Something'll have to come out. Here! I'll leave you this, for luck."

She dumped one of her bargains on the floor, and stuffed the fur coat in its place.

"There! So long, Ginger." Her farewell was cheery. But she did not glance at the silent figure on the bed.

Ginger heard the slam of the gate as she recovered consciousness. She felt empty, as though something had eaten away her heart.

Then—she remembered. Slowly she opened her eyes.

A ray of winter sun fell across the floor. It lit upon the object which had been discarded by Mrs. Pomeroy.

It was her pillow.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.