RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

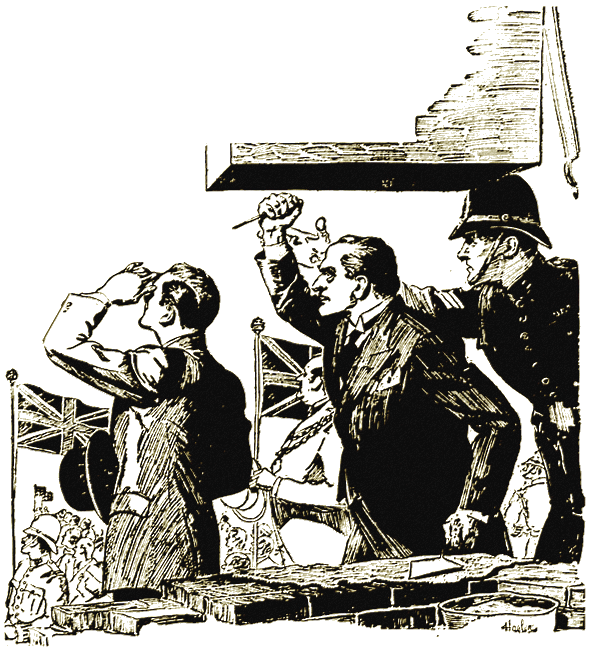

The blow never fell.

A wife's hunch helps her policeman hus-

band uncover a surprising murder plot.

VIVA RICHARDS had one of her hunches about the Royal Visit to Tudor Green, and, as usual, she managed to infect her policeman-husband with her own foreboding. No one could understand the secret of her influence over him. Besides being an Oxford Boxing Blue, he had a trained mind, while she was small, nervy and as full of superstitions as an old wife.

But for all that, she had her big husband by the short hairs.

It was grilling weather towards the end of August, so that he was glad to get off the baked pavements of High street into the cool of his home. Viva—looking like a high school girl in her tight dark-blue frock, with white collar and cuffs, had tea waiting for him on the daisied lawn at the back of the cottage.

She flew at him, kissed him, rescued the dish of plums from the wasps, poured him out a cup of tea and then looked at him with dark, tragic eyes.

"Bread and butter always tastes of grass out-of-doors." she said mournfully. She added in the same breath, "Hugo, I'm so unhappy about the Royal Visit."

P.C. Richards groaned, for he was sick of the subject. He considered that the residents of Tudor Green had swollen heads and had lost their sense of proportion over the civic honor. Besides, the affair was only small beer—a rushed visit of under half-an-hour. The prince was actually scheduled to fulfill an important engagement at a large industrial city, but with unselfish good nature had consented to break his Journey to lay the foundation stone of the new hospital.

"I'm unhappy, too," Richards informed his wife. "I have to be on duty. But I can't see why you're mourning."

"Because—Hugo. I know there's going to be a terrible tragedy."

He ran his finger uneasily round the inside of his collar, as though it had suddenly grown unbearably tight. Although he always laughed at Viva's presentiments, he had noticed that there was usually a logical origin in a tangible fact behind her tangled fancies and intuitions.

"What makes you think that, infant?" he asked.

"I'm not sure. One can never be certain, for warnings are such shadowy things. But I think it's this burglary at Sir Anthony Kite's."

He laughed indulgently, for it was obvious that, this time, she had strayed too far from any connecting sequence.

"It's queer," she went on. "I feel It must be leading up to something." Then her voice changed to professional interest. "Do you expect to make an arrest?" she asked.

"No, to you. There's not a clue. And the stolen notes are all old ones, so we can't trace their numbers."

BOTH he and his superior—Sergeant Belcher—were

annoyed by the affair, for burglaries were practically unknown in

Tudor Green, while the special circumstances made it appear an

outrage. Sir Anthony Kite, who was a well known London ear

specialist, had retired to live in the little old-world town.

but, owing to his persistent interest in his profession, he saw

local patients at his private residence, besides giving his

services to the hospital and clinic.

It was really a gesture of benevolence to the community, so that he was both bewildered and hurt when he came downstairs, on the preceding morning, to find that his study had been entered, through the French window.

Apparently, the burglar had either been disturbed or in a panic, for he had roughly forced a drawer in the desk and grabbed its entire contents, which included private papers and records, besides treasury notes to the value of 52 pounds.

Viva noticed her husband's frown and changed the subject.

"Mrs. Greenwood-Gore has a Union Jack dress for the ceremony. Red, blue and white. It positively shouts loyalty. It sounds pretty grim, but she carries it off. She is so lovely."

She could afford to be generous in view of her husband's antipathy for the local beauty and social leader of Tudor Green.

"Why don't you like her, Hugo? She's always gracious to you." she reminded him.

"She's gracious enough to talk to me, but she rarely takes the trouble to listen to what I have to say. Because I'm a policeman, I suppose ... Well. I must toddle back to the station."

Viva walked with him to the front gate, where they lingered to get the effect of the decorations of High street. They were on a lavish scale and presented a regal spectacle of fluttering scarlet and gleaming gold.

Even as they admired them, a cloud passed before the sun, so that the bright colors were suddenly dimmed, while the gilded crowns turned dull, as though tarnished by the poisoned breath of anarchy.

Richards felt Viva's sudden shiver and knew that she was reading an omen of evil in the eclipse.

IN spite of the heat, he hurried back to his work.

Notwithstanding his common sense, he felt vaguely apprehensive,

as though he, too, had prescience of certain seemingly

disconnected events which were already beginning to fit

themselves Into a dark and abominable conspiracy.

When he reached the station, he found his superior officer, Sergeant Belcher, listening with the grim expression which betrayed opposition, to Col. Clarence Block ... The sergeant was not only a popular local sportsman, but a native of the place, and he instinctively distrusted a newcomer to the district.

Colonel Block suffered from that handicap, but, against precedent, he had forced his way to the top, through sheer pressure of wealth and a plus-personality. Consequently he had crashed the position of chairman of the reception committee, on the occasion of the Royal Visit, to the annoyance of the mayor, who was a dignified, silver-haired lawyer, of long pedigree.

The sergeant addressed Richards skeptical grin.

"Extra work for you, Richards. The colonel's got the wind up about this Royal Visit."

The support of Viva's presentiment came from such an unexpected quarter, that it stunned Richards to silence. He could only stare as Block began to explain.

"I've made myself personally responsible for the safety of His Highness, so I'm insisting on extra precautions. I've Just carried my meeting, in the teeth of strong opposition. Now I want the co-operation of the police."

"I can't see what there Is to worry about in a loyal little town like ours." objected the sergeant.

"Then you can't see further than your nose. Don't you realize that the prince is going to a big Industrial center, with a strong communist element? Of course, the police will concentrate on making that borough safe for him ... But if a mad dog escapes their roundup, if he has any sense, he will come to our little show, where he'll have the chance of a lifetime."

"Hum ... What do you propose?"

"I'm going to have all the Territorials on the ground, so as to crowd out the general public. And I'm going to limit strictly the number of those present in the enclosure, for the ceremony."

"All right for your friends, colonel, but rough on the townspeople who've spent their money on decorations."

"They can line the route. And you needn't talk of my friends. They'll soon be my enemies, for I'm going to boil down the list of invitations to the bone. But my back is broad and I'm used to taking hard knocks."

P.C. Richards looked at him. He noticed the strong featured face, the bull-neck, the aggressive lips, the dark blood-shot eyes, the coarse hairs which covered his hands—and decided that his claim to resistance was no idle boast.

The colonel continued to lay down the law.

"There is to be no broadcasting. No photographers and no pressmen, except the local rag. And no planes are to fly over the ground."

"Then you had better speak to your son, colonel."

Block scowled as he walked to the door.

"If that young cub of mine breaks the regulations." he said, "I'll make a point of being on the bench, to give him the maximum sentence."

The sergeant grinned at Richards as the door slammed, for the strained relations between Block and his only son was common knowledge.

"Too gentle for this world," he remarked. "The angels must be calling him. There's the telephone. Take the call, Richards, and if it's Sir Anthony again, I'm not to."

Richards grinned, for the ear specialist had been continually ringing up the station, to inquire if the police were on the track of his burglar. On this occasion, however, and to Richards' astonishment, he had some news for them.

"My casebook has just been returned to me by post," he said in his dry, clearly articulated voice. "Apparently the perverted person who stole it has some muddled idea of making a gesture."

"But it's very satisfactory," remarked Richards heartily. "The loss of confidential documents must be the worst part to a professional man."

"I'm glad I've raised your spirits ... But my 52 pounds were not returned."

"I'll be round now to examine the postal wrapper."

"I have already done so. The only deduction from the postmark is that the criminal is spending my money in London."

P.C. Richards rang off, wiping his brow. His only consolation was that, at long last, he must go home to Viva.

WHEN he walked home, in the greenish dusk, he chose the back

way beside a small brown river; shaded with masonry, which flowed

through part of the town. Even here, his luck was out, for

instead of avoiding people, he ran into Mrs. Flora

Greenwood-Gore.

A flawless blonde—ageless and childless—she was the wife of an important man. Even the prejudiced Richards had to admit her beauty as he looked at her perfect complexion and violet eyes. He noticed that she was wearing a frock printed with poppies and cornflowers on a white ground, before she drew his attention to it.

"My royal reception dress. My husband says the colors are too daring."

"They've done more than dare. They've hit me in the eye," said Richards.

As she was not married to him, there was no reason for Mrs. Greenwood-Gore to smile at his joke. She went on talking in her habitual monologue.

"Oh. by the way, a man we knew in the Transvaal has just flown over to see me. I had to go out, so I sent him over to your wife, as he met her uncle at the Cape. I'll ring up when I get home and you can send him over ..."

She passed on, leaving Richards indignant with her autocratic management.

WHEN he reached the small, cream-washed building which held

all he loved most, the French windows of the drawing room were

open and the light fell on a patch of vivid green grass. As he

lingered, he could tell, by the halting sound of voices, that

both Viva and her visitor were finding it difficult to sustain a

conversation.

He plunged to the rescue, when Viva gratefully introduced him to the South African. He was a dried-up man with a nasal voice and no entertainment value, so that Richards was justified in not realizing his supreme importance in the development of future events.

There was nothing to tell him that had that especial man not called that evening, the course of history would have been changed.

To make amends for his first stiffness, he produced whisky, which presently unloosed the stranger's tongue. Even then, he was not a success, for he annoyed the Richards family by tactless praise of Mrs. Greenwood-Gore.

"Loveliest woman I've ever met. They were big people in Jo'burg, but she hadn't a scrap of side. Always the same to everyone. And she's not altered a bit. I do admire the way she puts it over."

"She certainly throws her weight about," said Viva coldly.

The stranger glanced at her quickly and then a change came over his expression. For the first time. Richards really understood what is meant by a poker face.

"Are you folks keen on flying?" he asked.

"Not me," replied Richards. "A policeman has to stand on his famous flat feet."

"Only way to get about. The drawback is the engine noise. You see, my job is in the cyanide works at Jo'burg, where the din is chronic. All the workers wear these."

He scooped out of his pocket a couple of curiously-shaped rubber plugs and tossed them down on the mantel shelf.

"Never without them. Always wear them flying ... Isn't that the phone?"

"I'll go," cried Viva joyously.

The South African's face lit up when she returned from the hall with her message.

"Mrs. Greenwood-Gore is waiting for you."

He was as eager to go as they to speed his parting. The instant he had gone. Richards dropped heavily down in his shabby varsity chair, which he had brought down from Oxford.

"The end of a perfect day." he sighed. Then he glanced at the mantelshelf and added. "That darned fool has left his gadgets behind. Well, he can fetch them himself. I'm not going to turn out again even to save the whole of the empire."

HIS ill temper and Viva's nerves were partly due to

atmospherics, for during the night, they were disturbed by a

flickering sky and the mutter of distant thunder. In the morning

it was pouring with rain and all day a succession of storms kept

rolling up over the hills.

As though the electric weather affected the general temper, the final meeting of the reception committee was an explosive affair. Colonel Block read out his revised list of those persons privileged to attend the ceremony, regardless of angry mutters of protests from those who were disappointed.

He was supported in his tactics by Admiral Stel—one of the oldest residents who was virulently anti-communist.

The vicar arose to make a protest. "I am sure we all appreciate your difficulties and your courage in tackling them." he said to the colonel. "But there is one person who should be present. Surely you could squeeze in Miss Spenser?"

There was a hum of approval, for the little spinster was a devoted parish worker and a zealous member of the Primrose league.

"It would break her heart to be left out," continued the vicar. "She has all the portraits of the royal family in her parlor. The memory of the occasion would remain with her always. Besides, in view of her deafness, she is deprived of so much amusement."

He looked for support towards Flora Green wood-Gore, whose fair face wore its habitual expression—serene yet remote—as though she dwelt on another plane. When she smiled and bowed her head, the applause grew so vigorous that the colonel had to give way.

"All right, since you insist, she shall have her ticket. And while we're on the subject, I have a special announcement to make. There will be no admission without a ticket. It doesn't matter who the individual or what the circumstances."

"I second the measure," approved the mayor. "It would take time to check a list at the entrance. In view of the rush, everything must go off without a hitch."

Unfortunately, after the concession, the meeting was marred by another incident. The admiral who was so staunch a supporter of home interests that he had not left Tudor Green for years rose on his gouty feet.

"I have been informed." he said, "that the presentation silver trowel and mallet to be used at the ceremony were not supplied locally. In my opinion, it is scandalous to spend one penny of the rate-payers' subscriptions out of the town."

"It was considered necessary," explained the mayor soothingly, "to avoid suspicion of favoritism."

"In any case," interrupted Colonel Block, "the expense will be carried by me, as my contribution. I'm entitled to choose my own firm, aren't I? I don't truckle to local graft."

After that implicit insult, it took all the mayor's diplomacy to prevent the meeting from degenerating into a dog fight. At its conclusion, the colonel made a final arbitrary announcement.

"The invitations will not be sent by post. They must be applied for, personally, at my house. I shall initial them myself and hand them to the rightful persons."

MISS SPENSER lost no time in applying for her precious card.

She enjoyed the experience as a little social occasion, for she

met others who were at the colonel's imposing mansion on the same

errand. While they waited, they were invited into the dining room

for refreshments and the spirit of the house was hospitable and

friendly.

It was fortunate that she had a taste of pleasure, because within five minutes of leaving she was the victim of a disagreeable incident. She went home by the short cut, a paved passage running between the garden walls of some large houses. At its darkest part, a youth rushed past her, snatched her bag and ran off with it.

She went immediately to the police station, to report her loss.

"Luckily, there was only a little money in it," she told Sergeant Belcher. "A trifle over four shillings. But my card-case and latchkey were inside. I shall get the lock changed instantly, but I do hope my cards will not be used for an improper purpose."

Then she gave a cry of dismay.

"Oh dear, Oh dear. My card of admission was there too. I shan't get another. The colonel warned me not to lose it. He will be so angry with me."

"Did you get a view of the young man?" asked the sergeant.

"The merest glimpse as he rushed under the lamp. Of course I could not be certain, but I thought he looked like young Block. Only that is too ridiculous."

"Well," remarked the sergeant; after the distressed lady had gone, "it seems one of two things. Either the dictator is so annoyed at being crossed over Miss Spenser's ticket that he arranged to have it pinched—or else the son did it on his own. He's been left out of the show and he may be planning some fool revenge on his dad."

P.C. Richards went home in a disturbed frame of mind. He kept asking himself a question. Could there be any connection between the loss of Sir Anthony's 52 pounds and Miss Spenser's 52 pence?

If such were the case, there might indeed be some foundation for Viva's miserable hunch. But although he thought until he was stupid, the two thefts remained poles apart, and he could conjecture no point of fusion.

He did not tell Viva about the incident until the next morning. She made no comment, but he was dismayed to notice her pale face as she poured coffee.

P.C. Richards found the light duty, which was his lot at Tudor Green, an arduous test of endurance. Of course, he told himself that he was worried solely about his wife and he watched the clock—or rather, his wrist—until he was able to get back to the cottage.

He was glad to find his father-in-law, Dr. Buck, having tea with Viva. He was a brisk, sensible man, with a tight pink clean-shaven face, and he would certainly disclaim the responsibility for his temperamental daughter. On this occasion, however, his gossip; had done nothing to relieve her symptoms, for her small face was pinched with anxiety.

"Have you heard about the admiral, Hugo?" she asked.

"No," replied Richards. "What about him?"

"He's fractured his leg. Daddy has just been called in to him. He fell down his front steps."

"Rather early in the day for that."

"No," said the doctor, "he was quite sober. The steps were greased. I nearly slipped on them myself."

"Who could have done it, Hugo?" asked Viva.

Richards tried to hide his uneasiness.

"Some silly practical joke," he declared. "But I'm off duty now and I want my tea..."

Although he refused to discuss the incident, he followed his father-in-law to the front gate.

"You might send over a bromide for Viva," he said. "She's got jim-jams."

"Even I have diagnosed them," remarked the doctor dryly. "I'll let you have a draught."

THE sedative did its work, for Viva had no warning dream to

relate on the following morning. The sun was shining from a clear

blue sky and she felt cheerfully normal. During the morning she

remembered that she had not even tried on the new frock which had

been bought for the ceremony. It required to be shortened, and

she grew so interested in her appearance that she had not time

for apprehension.

She was dressed and seated at luncheon table when Richards entered the room.

"Aren't you cutting it rather fine?" she asked

Then she noticed that he had made no comment on her new finery, although he was usually responsive.

"What's the matter?" she asked.

"Nothing," he replied with forced lightness. "Bad show for Flora Greenwood-Gore. That's all. She's going to miss the fun."

"You mean—she won't be at the ceremony? Why?"

"Got a telegram, early this morning, saying her mother was dying and asking her to come immediately. Her husband is away, so she wired him where she'd gone, before she left. He rang up the old folks to find out exactly what was wrong ... and nothing was."

He stopped speaking, and gazed at his wife in consternation. She sat motionless, her fork poised in the air, while she stared fixedly at him as though her wits had deserted her.

"What's the matter?" he asked sharply. "Say something, but don't look like that."

"Dear Brutus," she murmured.

"My dearest girl, it sounded like you said 'Brutus.' Or am I imagining things?"

"No, I said it. Hugo, don't you remember Barrie's play, where a lot of ill-assorted people were invited to a house, because they had something in common?"

"Yes. But—"

"Don't you see? Someone has prevented Miss Spenser, the admiral and now Mrs. Greenwood-Gore from coming to the ceremony. There's an object behind it—and I'm terribly afraid. What have those three people got in common? What?"

Although he was six feet of stodge, P.C. Richards felt himself beaten by his wife's hunch. He became conscious of something secret and diabolical creeping in the darkness, like a slow train of gunpowder eating its way to the explosion.

He glanced at the clock distractedly.

"If you are right." he said, "we've got to find it out in double quick time. We must be in our places in 15 minutes."

"I know. Think. Hugo."

"It beats me. I could find points of resemblance between the admiral and Miss Spenser. They are both elderly and rheumatic and amateur gardeners and Primrose leaguers and deaf. It's Mrs. Greenwood-Gore that's the complication. She has everything they haven't got."

The telephone bell began to ring, but he shook his head impatiently.

"Shut up," he muttered.

"Answer it," commanded Viva suddenly. "I feel it may be important."

Obediently, he took the receiver off the hook. He was strung up to a pitch of nerves when he wanted to swear at the sound of Mrs. Greenwood-Gore's voice at the end of the line. She was furious over her grievance and insisted on telling him what he already knew, In spite of his efforts to interrupt her.

"I've rung up the police station," she said, "but I can get no responsible person. They say the sergeant has left for the ceremony. So I appeal to you. You must find out who sent that telegram and prosecute the person."

"I'm not sure a practical joke is within our province," he told her.

"Thank you. Now I have your promise, I feel satisfied."

"I'm afraid you didn't hear. I said it's not within our scope—"

"I hope so, too. Goodby."

P.C. Richards rang off and stared at his wife as though he could not be believe his ears.

"Viva," he shouted. "I've got it. I now know what they have in common ... They are all deaf."

Viva shook her head.

"Not Mrs. Greenwood-Gore," she protested.

"But she is ... That South African chap—Yes, that's the idea."

Dashing across to the mantelshelf Richards began to turn over the ornaments.

"Where are his gadgets?" he panted. She instantly picked up a vase, turned it upside down and shook out the plugs. "Why do you want them?" she asked.

"Because I want to make myself deaf. It seems to me that there's going to be a planned disturbance at the ceremony—probably some noise. That's why they've eliminated all the deaf people. They might not react to the distraction—whatever it is ... Well, they'll have me now."

"What will you do?"

"Just act on the spur of the moment. Come along. The car's outside."

Standing in the over-heated enclosure. Viva heard the cheers which were inaudible to her husband. He had motioned a constable to stand by him, but otherwise, he could only wait and watch.

THE great moment was at hand. The cheers grew louder as the

prince entered the enclosure. He was accompanied by the mayor and

mayoress, who had met the royal train at the station, and he wore

the rosebud which had been presented by their grandson.

Colonel Block—as chairman of the reception committee bowed himself forward with a few words of welcome, to superintend the laying of the foundation stone. There was no time for speeches and the short ceremony was soon over. Having done his part, the prince glanced at his watch and then smiled at the company, with his customary charm.

At that moment, there was an unexpected commotion. With a threatening snarl, which grew louder every second, an airplane swooped down out of the clouds and dived lower and lower over the ground, while the roar of its engine increased. Instantly, every head was turned in its direction while every face looked upwards.

There were two exceptions to the general company of sky-gazers. P.C. Richards heard a deadened noise, but the sound reached him a fractional period later than the rest of the crowd. It was in this interval that he, alone, saw what was about to happen.

Colonel Block whipped a knife out of the handle of the silver trowel, as though it were a sword-stick and poised it, ready to stab the prince in the back.

The blow never fell. While the company, including the prince, were still engrossed by the antics of the airman, who was flying in dangerously low circles. P.C. Richards and the other constable had gripped their prisoner and run him out of the enclosure, with the minimum of commotion.

The incident passed with such despatch that afterwards, no one could claim truthfully to be an eye-witness of the outrage ... The prince laughed and hurried back to his car. There was a second outburst of cheers along the return route to the station. Soon afterward he was back in the royal train, only conscious of an amusing break in the boredom of a municipal ceremony.

THAT evening, at the cottage, there was a festive meal, when

P.C. Richards returned—full of importance—after the

excitement of the proceedings at the police station.

"The Blocks," he explained to his wife, "are paid agents of the Wrecker gang, whose aim it is to upset the peace and security of the world. Father and son worked together, hand in glove. The feud was a dodge to throw dust in our eyes.

"Of course, they were going to be very well paid for bumping off a royalty. The son did all the active part. He stole Sir Anthony's casebook and Miss Spenser's bag and he greased the admiral's doorsteps. As you saw, he did the flying stunt for which his father was going to inflict a heavy penalty, according to plan."

"That was a smart idea," remarked Viva, "If you watch a crowd when a plane files low overhead, I defy you to find anyone who does not look up instinctively."

"Exactly. Block's part was to strike instantly in the confusion and then to slip the knife back, before the murder was spotted. When it was discovered, it would be difficult to associate him with the crime, as they all had an equal chance."

"But wouldn't the knife be traced to him, as he ordered the trowel?"

"He would probably take it away during the uproar. Remember, there were no brainy C.I.D. men present, to take command and order everyone to be searched and all that. I don't see why anyone would suspect the trowel. And if it were found, he would probably be able to prove delivery of an innocuous duplicate and swear to substitution on the part of persons known, in order to frame him."

"But when did you get on to the idea that Mrs. Greenwood-Gore was deaf?" asked Viva.

"When she began to guess at what I was saying on the telephone. I wonder why we never spotted it before that she was deaf. It explains why she goes on talking and never seems to listen. Sheer bluff. My own idea is that she is much older than anyone knows and like many beautiful women she can't stick the thought of age or infirmity. You remember how the South African talked about her putting over 'something.' That chap knew."

"Well, it's all very clever of you, darling." said Viva. "But don't forget Block had to steal Sir Anthony's casebook to find out all the cases of deafness in the district!"

"What of it?" asked her husband.

"Well—wasn't that my hunch?"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.