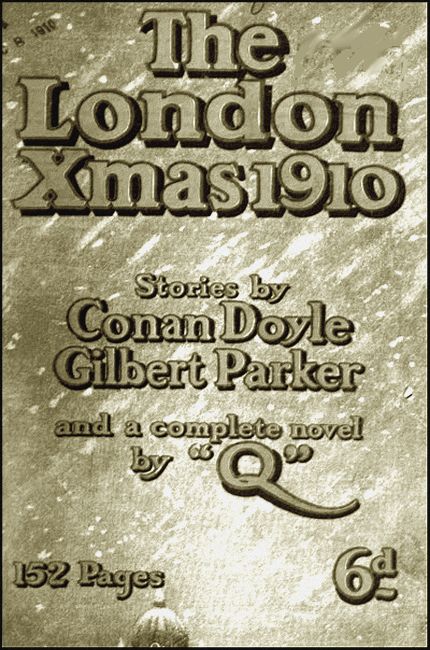

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

The London Magazine, December 1910, with "Thumbs Down!"

CHESTNUTS were going strong—both before and round the fire. As the nuts on the bars frizzled and popped, hoary jokes were brought out again and aired. A jovial-faced man propounded the old teaser of "The Lady—or the Tiger?" When he paused for breath, his hearers rushed into the breach, each ready with a positive answer to the Riddle of the Two Doors. Their host laughed derisively.

"You youngsters are all mighty cocksure. Prehistoric—all of you. I'm listening to your rubbish with respect, for the reason that at least one half of you might be right. But the one man, whose opinion I'd like to hear, sits glum. Come on, Drake, which did he meet? Lady or tiger? Don't be afraid! It won't let you down. Angels' feet have been pounding in everywhere."

He winked jovially at the pretty girls he loved to collect round him.

Drake drew further back into the shadow. He was a long, lean man, with puckered eyes. To make up for his narrow girth, he possessed a world-wide reputation.

"Without prejudice," he said. "I don't care a hang which it was. The fellow sounds rather like a grafter. Anyway, he's comfortably dead now, whichever way he went out. But it makes me think of a similar cases in which I happened to—My eye! What a fool I am!"

He rushed in with a vengeance. The circle round the fire would take no denial.

"Well, stoke up with the chestnuts, then," snapped Drake, "for it's Lombard-street to a China orange you won't swallow my yarn. It happened just after I'd returned home from Henshaw's expedition into Central Africa. I came back to find myself very seedy—eye trouble—and what was worse, a marked man. Lumps of Henshaw's well-earned fame had come pelting on to me. As a matter of fact, he did everything off his own bat. I simply went with him and did the cooking—records and all! Oh, shut up! Very well, then. Do your own talking!"

"Go on, Simon! Don't be a coward!" said a gentle-faced woman in the corner. She was Drake's wife and, incidentally, a great talker.

The famous man obeyed instantly.

VERY soon, I got fed up with strangers, and was only too thankful to accept an invitation to stay with some people I knew fairly well. Oddly enough, at the very start of my entering the house, an incident occurred which was significant and which was the keynote of the visit. No sooner was my foot inside the door, than a heavy bag of flour tilted down on to my head. A practical joke! I entered the house with white hair, and I left it with my hair white for good, as you see it now, from the same cause.

I won't pretend that I enjoyed the first few days of my stay. I had been away so long that I couldn't catch on to the new spirit that had crept into society. The Groves were a specially nice family, and the house-party, on the whole, consisted of a thoroughly good set. But the entire lot was infected with a craze for idiotic ragging. It didn't appeal to me. I was used to brainless frivolity—used to meet it in chunks among the monkeys and natives. And I was used to danger. Old Henshaw saw to that. But this particular blend of dangerous joking that animated the antics of the house-party gave me a positive pain. It was simply fierce. I got on to the subject with a very decent fellow—Derby by name—who was also staying in the house. He liked the tone as little as I.

"Dora Groves brought it back after her visit to Beecham Towers," he said, "and her people froze on to it, because they think it's the hall-mark of the Smart Set. They've done nothing sensible since. Rag, rag, rag—from dawn to dewy eve. And the idiots don't know where to stop. There'll be serious trouble before they're through."

"I'll put an end to it," I said. My own confidences make me smile. I'll say straight away, I was a humbler man afterwards. I couldn't tackle my host and hostess—but I got hold of Dora and let her have the great guns of my wrath.

"Look here, Dora," I said straight. "You were the jolliest little kid in creation when I left home, and you're tho jolliest big one now." But I lied, for there was staying at the house then the very nicest girl, of whom more hereafter.

"Frankly," I went on, "these idiotic monkey tricks aren't worthy of you, Dora. They're dangerous, they're brainless, they're discourteous. They're dead against the spirit of hospitality, for which your family is famous. Do make a stand against them, like the dear, brave girl you are. The rest will follow your lead."

She tossed her head contemptuously, and peppered me with small shot. She must have thought me a fine specimen of a long-lipped, weak-eyed kill-joy.

"I'm sorry if our fun has disturbed you," she said. "I should have thought a man of your reputation wouldn't have grumbled about a few jokes. But I'll tell the others, in future, not to try to score off you, as you think it dangerous!"

Off she went, with a cracker in her hand, and a second later the cracker went off—under the door of an invalid spinster. I tackled the lot of them in turn, with about equal success. They took their tone from Dora, as the eldest girl of the family, and she—in turn—was completely infatuated by a fellow of the name of Puffin Lake.

He was the ringleader of the rag. I don't want to do this man an injustice. At the same time, if I were to do him justice, you'd think I was infringing the law of slander. So I'll content myself by saying he was a virulent waster—too brainless to be vicious, too mischievous to be harmless. In a strait-waistcoat, or a monkey-house, he'd have been quite a decent fellow, and good company. I like to be fair.

I lasted out about four days of my visit, keeping a pretty stiff lip, considering my disgust. You can imagine, I was not exactly popular. In return for my gift of the cold shoulder, I got any amount of cool cheek. I did not meditate, however, making tracks for some other cover, when an incident took place which altered my views. I said something about a nice girl who was staying in the house. She will have to figure in this yarn again, so I will put a name to her—not her real one, for obvious reasons. I intend to call her "Silence."

The night in question there was an impromptu dance in the hall. It was the usual combination of a football scrum and a bargain-sale. During the lancers, in the middle of a ring, some fool loosed hands, and the whole lot went flying, like a bead necklace when the thread is snapped. The girl I called silence went spinning into space, made several cannons against different bits of furniture, and ended up with a mighty crack.

My rage was an eye-opener to me. I wanted to charge the lot like a rogue-elephant. I pounded over to help Silence, but directly I hauled her up, she collapsed. Her ankle was broken. After that, there was no stopping me. I let them have my unvarnished opinion of them, served up piping hot, and without trimmings.

"Look here," I said, only I put it stronger, I'm afraid, "fooling is fooling, I grant you, and no harm done. Tea-tray tobogganing and pillow-fights are capital sport, and only come rough on the carpets and pillows. I don't grudge you your greased-pig chase you had round the house, yesterday, for I grant that, at least, you were in congenial society. But, when it comes to a lady being injured, I say your conduct is not worthy of decent fellows—let alone gentlemen! You're about equal to the lowest set of apaches!"

There was a sort of stunned silence. Mrs. Groves, who is a sweet, fat-baby sort of person, bleated out something about "young folk being young folk." It was her idea of saving the situation. Old Man Groves stuck out his lip and snorted like a cross infant. I knew his sympathies were with me. He had been too badly hit, through his furniture, to approve the rag.

However, things went a trifle slower after that. We actually had a quiet evening the next night, when we bawled out songs from the musical plays. Puffin Lake also entertained us with animal imitations. I will admit—being a fair man—that his imitation of a monkey was pretty nearly perfect. Instinct, I suppose, which I maintain is a throw-back to some previous existence. As I watched his antics, my thoughts went back to steaming forests, and I saw again the creatures leaping and gibbering among the matted ropes of creepers overhead. I wondered how the girls could tolerate anything so lifelike, but to my amazement their enthusiasm was fierce. Not to put too fine a point to it, he possessed the dough.

So far, I'm afraid I must be boring you with this yarn. None of tho thrills I've promised you! Too much of the flour-bag! You're wondering where my whitened poll comes in. Sit tight! I'm coming to the other half, where the grin adds a pothook and turns to "grim." It's as difficult to divide the two bits of the yarn as to separate a snake into neck and tail.

It appeared that I had offended Dora over the dance episode. Her head did overtime tossing, so I arranged to go, after the fancy-dress ball, which was to take place a few days later. I never went to it, however, because of the events that took place the night before. With your leave, I'll hop right into that evening.

I was walking in the park, about 5 o'clock, in the company of Derby—the nice fellow I mentioned—and with Puffin Lake. No company about him! It was a nasty evening that reeked of rheumatism. The wind was whistling as shrilly as though it had its fingers between its teeth, and had a bite on, as well. Leaves lay about in rotting piles. The sky had a dirty look, as though the Fiend had trodden heavily on the mud below and spattered the sky with splashes.

Just as we were turning homewards, we met a couple of men. I recognised one of them immediately as being a keeper from the Zoo, which lay the other side of the park. He stopped, knowing me at once from the villainous woodcuts in the rags, which shows how closely they must resemble me. He told me that they were in a stew, as a gorilla—a recent purchase—had made its escape. They were trying to keep it dark, and were organising battues all over the park to trace the brute.

Naturally, our depression vanished on the spot. We were all as keen as mustard, and volunteered to help "in the hunt.

"Is he savage?" asked Lake.

"I wouldn't advise you to take liberties with him," answered the keeper. "Either he'd toss you up in the trees like a pancake, or make you into mincemeat."

"Sounds like a chef!" grinned Lake.

I'll do him the justice to admit that, contrary to my expectations, he did not show any fear, but capered with excitement at the sport. Very likely he hadn't the wit to understand danger. Derby also showed no signs of the white feather, although a dreary park, at shadow o clock, with a possible gigantic ape waiting to drop on one from a tree, is not a cheerful spot.

I'm free to confess that, of the three, I was the most afraid. This sounds odd. The keeper had stopped me purposely, feeling the hunt was in my line. In Africa, day after day, I used to cut my way through forests that supplied plenty of cover for a varied assortment of attacks. I suppose I got case-hardened, for I don't remember feeling especially scared. Yet in the middle of those few acres of park, with the lights from houses and villas twinkling in the distance, my heart was in my mouth the whole time.

It was the idea of the unconscious population that got on my nerves. I thought of sleeping babies in mail-carts, innocent youngsters, careless errand-boys, defenceless maiden ladies, feeble old men, any of whom might cross a lonely corner of the park at any moment to fall a victim to the great simian that lurked somewhere in the undergrowth.

I wanted to thrash every acre to the place until we had unearthed the brute, but we had to give in at last, so as not to be late for dinner. Unpunctuality was the only sin that good Old Man Groves could not forgive.

I went into the big house, full of light and bustle, with a queer, feeling of depression at the thought of the danger still at large in the darkness outside. The first thing I saw was the nice girl—Silence—lying on a couch. She gave me a smile when she saw me, and it flashed across me—a rough, chap who had tramped thousand of weary miles in his time—that it was a good thing to have a smile of welcome at the end. She—bless her—lying there helpless, stood for one of the things we'd fight to protect from all danger present and to come. I went up to dress, feeling the Adam's apple in my throat swelling to a football.

Half way down the corridor Lake sang out to me to come into his room. Spread out on his bed lay an ape's get-up, which he had just sent for from town. It was his costume for the ball. And he wanted my opinion. I think he was surprised at the warmth I bestowed upon his choice, for he wasn't used to giving my approval.

"You'll never look better again in your life," I assured him. "You'll make a thundering good-looking monkey."

He stood there, grinning under the electric light, his puffy pale face and little eyes reflected in the mirror.

"By Jove," he said, with a sudden flicker crossing his features. "What a rag it would be to put it on now and make the girls yell! They'd think it was the gorilla from the Zoo."

In an instant I had my paw round his arm. The gorilla's grip was nowhere in it with my clutch.

"D'you mean to say you've let on to them already about that?" I shouted. "More shame you, then! But I tell you what. You don't stir from this room until you promise not to play any infernal trick in this matter!"

He told me I was no gentleman, and I agreed with him so promptly that it took the wind out of his sails. He liked to have his opinions endorsed. In the end I had his word to abstain from fooling, and I admit I insulted him in my own mind, by wondering how much it was worth.

When I got to my own room, I found that I was in a bad way. I went straight to pieces. My eyes were throbbing as though they had engines inside their balls. I saw shapes stalking me from every corner. I clapped a cold sponge at the back of my neck, but it only ruined my collar. After tying a disreputable bow I turned to a drawer and took out a certain little shooting-friend of mine that has been with me in many a tight corner. Instinctively, I slipped it into my pocket. It made a shocking bulge, besides being incorrect, but at the very feel of it my depression and seediness vanished. Nothing like iron as a tonic for the system!

Dinner was a peaceful meal that night. Something was in the air that seemed hostile to the usual scrap. The servants got through their tasks with relieved faces. Personally, I felt the lull was unusually soothing as I chatted to the nice girl—Silence—who was wheeled in for the meal.

After dinner we all sat in the hall. It was a big, old-fashioned place, oak-panelled and low-ceiled. At one end was a great window, set above a sort of gallery. The house, I'm sorry to say, has long been swept away to make room for the villas and flats that are spreading over the place like fungus.

"Turn out the lights," commanded Dora, "and we'll sit in the dark and tell ghost-stories! That is," she added spitefully, "if Mr. Drake has no objection." Just before the lights were turned down I looked across at Dora. I noticed that she was sitting close to the door. By her side was Lake, and their heads were very close together.

The next minute—darkness

"Yes; talking does make one thirsty. Rather cold, isn't it? Anyway, I'll depart from my usual custom. Three fingers, please! Thanks!..."

Well, to go on... Very soon we were in full blast. A pretty, dark girl, who looked rather hungry, started a spiritualistic story. She managed to hold our attention with a grip of which I should not have judged her capable, and we were hanging on her words when something stirred in the direction of the gallery. We all looked that way. You would have thought our eyes were all connected with one switch, the way they all turned together. I suppose our nerves were on the stretch from the story. We were keyed up and receptive. The air seemed to tingle and crackle as we waited for a tense moment. Tho whole of what followed happened almost in a brace of seconds, but it will take me much longer to tell. Against the dim square of the window something appeared like the outlines of a gigantic, squashed spider. A crouching form—huge, hairy, monstrous—shot through the frame, and, in one spring, landed almost on the rail of the balcony.

Everyone screamed. Panic was loose in a second, and hopping about like a drop of quicksilver. The groups in the hall broke up like the pieces of a kaleidoscope. One shake, and every one had left his place and was swarming towards the door. Only one person remained in tho deserted spot by the gallery. She had to stay because her foot put her out of the running. It was the nice girl Silence!

I rose to my feet with the rest. Instinctively my hand went to my pocket, and I was covering the crouching form up aloft. I wish I could move this tale along quicker. Remember, it is all passing at record rate. Then, shall I ever forget the concentrated horror of that moment! Two shrieks rang out:

"Shoot man, shoot!" shouted Derby. "The gorilla!" His voice was simply charged with command and conviction.

Almost simultaneously Dora cried out in an agony of appeal: "For God's sake, don't shoot! It's Puffin!"

Now, you, who sit here calmly, try and get inside me, as I stood there faced with the whole responsibility of action. You've been laughing over the old teaser—Which Door! The Lady or the Tiger? Put yourselves in my place as I stood there and grappled with the appalling problem of the man or the monkey? And remember the issues at stake. Mind, I had no time to think it out, to reason calmly, to decide dispassionately. No brainy Sherlock Holmes theory flickered across my brain. Everything had to be settled, as settled it was, between the flutter of a lash, the drawing of a breath, the pause before an ape's spring. Which stood there before me?

For the life of me I could not tell. Remember what I told you of my eye trouble. In the dim right it was impossible to distinguish any salient point of difference. In just the same way I was faced with the double poser. To whose appeal should I respond? Derby's or Dora's? Again I say, put yourselves in my place. Derby was a sensible fellow. He was keen—no fool. He yelled to me to kill the brute.

On the other hand, the whole affair was stamped with the brand of a practical joke. Dora had been sitting with Lake. She must have known if he had slipped from the room. She was possibly in his confidence. I remembered the contempt with which I had received his reluctant promise to abstain from fooling, also the faithfulness of his monkey imitations and the perfection of his masquerading costume. Added to this, Dora's voice was wrung with the agony of conviction as she screamed: "For God's sake, don't shoot!"

Very likely you will think I should have aimed low. I say No! You aim low to wing a man, but to disable a great ape is not to stop him but to infuriate him to madness.

There I stood, faced with the awful riddle. Man or Monkey? Monkey or man? If I fired I might have Lake's blood on my head. If I held my hand I thought of the helpless figure of Silence, lying in the path of the brute. But I do not believe it was then my hair turned white. A long time to tell what happened! A second. In my hand was life or death. Such a responsibility is too heavy for mortal powers. It is rightly in the gift of Higher Hands. But in that moment I accepted the charge. I decided.

Pray you may never know the agony of such a choice! I deliberately singled out a fellow creature for death. There was a chance either way. But I could not give Puffin Lake the benefit of the doubt, Just as he was in the midst of his fooling, I prepared to sling him into eternity, to appear before his Maker with the grin still on his lip. I firmly believe that it was in that instant that my hair turned white.

I sighted, fired—twice, thrice. There was an inhuman scream, a fierce choking struggle, and then we knew that whatever lay there in the gallery was dead. Some one turned up the lights. Why not before, you say. I repeat it was the work of two seconds. I, distraught and capering like a maniac, was the first to race up the steps to the gallery.

We found there, all crumpled up and distorted, the body of the gorilla. Derby had been right. At the sight I did a queer thing—when I was a tiny chap I took my tannings mute. Yet I sat down and cried like a baby, and then cried and cried again.

I believed that I embraced Puffin Lake like a brother. It is the most painful recollection of the lot. That's all. I came out of the house the next day with nothing to the good but a crop of white hair.

DRAKE stopped and rumpled his white poll.

"Did you get nothing else?" inquired a girl.

Drake shook his head.

"Nothing?" persisted the girl. Again he smiled. He was not to be drawn. He looked across at his wife. She was a very nice woman. At one time she must have been a very nice girl. But then, no one could ever call her Silence.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.