RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

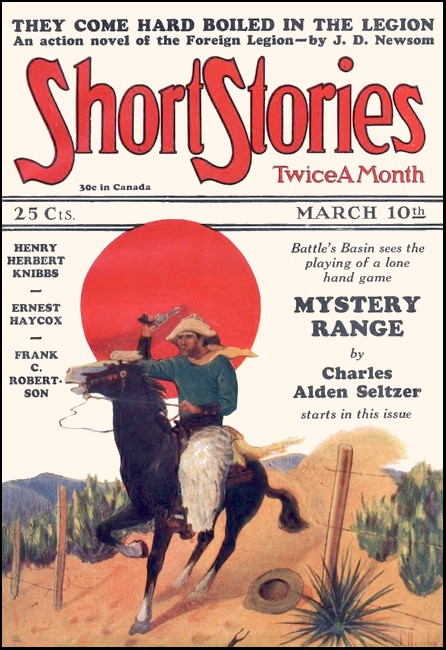

Short Stories, 10 March 1928, with "Bound South"

Drifting south, lonely cowboy Joe bumped into Canyon—and Canyon, all agreed, was one bad town to bump. But in an hour Joe rustled two meals, saved a ranch, found a friend and drifted south again.

THE day promised to be fine as Joe Breedlove mounted and swung out of Prairieville. He had breakfasted well, there was money in his belt, and a sound animal carried him. It was late October; rose flame spread all along the eastern rim and the air was clear, thin and sparkling, Down in the brakes the trees glowed yellow and crimson. The ridges, wet by a recent rain, showed a verdant tinge. It was a morning to make a man heady with the surge of his blood and the expansion of his spirits.

Even so, Joe Breedlove rode off in a pensive state of mind. He had seen an old and chosen friend married the day before. Married and settled on a ranch. And, while rejoicing at his comrade's luck, he saw the ringer of destiny point him out henceforth as a lone rider, a solitary wanderer. Hereafter he would sit beside the night fire alone, watch the distant stars alone. Once he would not have minded, for early youth has a way of being self-sufficient. Joe, going along his thirties, felt the need of friends. It was the way he was built.

He rode with a smile on his lean face, the smile of a man who looked at the world with shrewd and tolerant eyes, of one who loved life but was never for a moment fooled by it. That, as a matter of fact, was the substance of Joe Breedlove; his was the nature to make allowances for all frail and mortal things, asking in return very little for himself. He was quite tall and ridden down to hard, slender muscle. His features were broad, generous; and his hair, where it showed beneath the Stetson, had a silver color that made him seem older than he was.

Thus he rode onward, busied with his thoughts and with the signs about him. It was a rugged, barren land as it reached southward, and to the casual observer nothing much met the eye. But to Joe Breedlove, versed in the country, it was an unfolding story. Here a lobo crossed the trail, his pads broad' and plain in the dust. Alongside were the flanking print of accompanying pilot coyotes. Twenty yards to the left he caught a flash of coiled orange and black under a sage bush. High overhead and farther along a buzzard wheeled in a steady circle, the sign it had sighted carrion on the ground. Joe watched the bird as he traveled, a kind of impersonal curiosity in his mind. But he would presently have forgotten it had he not quite of a sudden arrived at a wide flurry of hoof-prints cutting athwart the trail. A cavalcade of men, traveling fast, had come out of the left ridge not long before and aimed straight for the rugged land farther west.

Breedlove studied these prints at some length, a kind of soft chuckle in his throat. "Six-eight men in a hell-bent hurry. Now what you suppose? Minions o' the law or gents escapin' the wrath o' justice? Not that it makes any difference, but it might be profitable to know."

He didn't know this country, but stray report indicated it was somewhat tough. Down at the southern end of the valley there was a town called Canyon and the name of it was a byword as much as five hundred miles northward where men in jest often said, "I'm goin' to kill me a sheriff some day an' go to Canyon." The theory rightly or wrongly being that this act was a necessary qualification to citizenship in the place.

JOE BREEDLOVE lifted his eyes again to the buzzard which by now had dropped lower and traversed a narrower circle. He wasn't certain, but he thought dust still hung over the cavalcade's trail in the west. Again the chuckle welled up. He swung his horse to the left, aiming at the buzzard's mark. "They say trouble comes to a fella that's got trouble in his heart. Well, pony, we're as pure of conscience as the driftin' snow. Nev'less we ain't goin' no place so lessee what's over there. It might be interestin'."

To the left he traveled, threading gullies, climbing the ridge's side. Stony pockets lined the ridge, ringed here and there by stunted pines. As he came beneath the buzzard's arc he took great care not to appear stealthy, slowing the pony and whistling the mournful bars of some old song. Likewise he kept well up on the ridge where he might be seen, and although his glance absorbed everything he appeared to be half asleep in the saddle.

"Buzzards," he opined casually, "ain't nowise healthy animals, but they tell a lot." Then he straightened a little. He had arrived at another of the depressions. In its bottom was a dead paint horse, saddle and gear stripped from it. But it hadn't been dead long, and Joe Breedlove, looking across the rim to where the pines bunched together nodded his silvered head ever so slightly. He dropped into the depression and from the saddle read a plain, commonplace tale. The animal had broken its leg in a gopher hole and had been put away with a bullet. Breedlove raised his head to the pines and spoke aloud.

"If you got me covered up there, jes' forget it. I ain't after yore skelp. Plenty to do watchin' my own."

And he rolled himself a cigarette, waiting. Several moments passed. Then the brush rustled and a man came from concealment, sliding down the slope, gun in his fist. He was a thin, undersized bundle of nerves with a fiery, impatient face. It was far from a handsome face, yet it bore no apparent depravity or wickedness. Breedlove, placidly smoking, set the man down as just another of those bantams who were forever bridling at injustice. Apparently the fellow had a gambler's spirit, for after a cursory glance toward Breedlove he dropped his gun into the holster, shoved his hat back over a jet-black cowlick and began to swear in melodious, flowing syllables. Even a bullwhacker would have acknowledged the artistry, the complete adequacy of that cursing. Breedlove smiled in benevolent, approving interest.

"Some men," he remarked, "are shore born with the gift. Nothin' lubricates the soul like a little well-chosen profanity."

"Was yuh ever in Canyon?" asked the stranger in a high pitched voice.

"No," admitted Breedlove, "I'm from the north. But I was rapidly vergin' tords that point."

The small one made expressive gesture with his hands. "Stay away, stay away, brother. Ninevah an' Tyre—they don't compete. Nossir, they don't nowise com- pete with Canyon. A sink o' iniquity, a stinkin' hog waller, a condemned blotch o' scurvy on nature's benign countenance." He looked at Breedlove almost meekly. "Amigo, I ain't tongue-tied, but I'd shore have to improvise on the English langwidge to name an' classify that Siwash smellin', snake-belly crawlin', festerin' heap o' boards what—"

"Ample," interposed Breedlove. "Plumb ample. I would gather Canyon had done you some great wrong."

THE small man's voice had a way of breaking and rising to falsetto in anger or excitement. It squeaked now like a pair of rusty hinges. "Wrong? Did yuh say wrong, amigo? Huh, what it done to me was a-plenty!"

He kicked at the loose stones with his feet, adding somberly, "But I guess I did a few things m'self. Did yuh see a passel o' beetle-faced gents sashayin' acrost the landscape down yonder?"

"I saw tracks cuttin' westward about two miles."

The wiry one looked gloomily at his horse. "Uhuh. They're a-follerin' a dead trail I laid down. Me, I'd been out of this stagnatin' country, by now, if the paint hoss hadn't struck a hole an' sent me to hell and gone on my coco." He squatted down and laid a brown hand on the animal's neck. "He shore was a good hoss, too."

Something inside Breedlove grew warm and friendly. He announced, through a ring of smoke, "Name's Joe Breedlove. Bound south. Nothin' in p'ticular. Jes' a-travelin'."

"I dunno what they took me for," muttered the small one, rising on his haunches. "I was a-mindin' my own fool business, which ain't usual for me, but nev'less I was readin' my own hole cards. Thunder, but trouble jus' popped up like a gusher comin' in! Out goes the lights an' bang goes the furniture. Well, when a man ain't wanted he'd orter have sense enough to depart. Which was what I proceeded to do even if the dang' fools tried to impede my progress."

"Some towns is mos' unusually clannish thataway. It takes a can-opener to get in an' a crowbar to get out."

"Uhuh," said the wiry one. He flashed a sidewise glance at Breedlove. There was something about this tall, serene man that inspired trust. It may have been the directness of his glance or it may have been the shrewd yet unsoured humor hovering in the corners of his broad mouth. At any rate, he invited confidence. The small one announced solemnly that it had been his aim and intent to hit for the Box U and find work with the beef roundup. Men, he added, called him "Indigo" Bowers.

Silence for a moment. Then Breedlove stretched forward his right hand and they shook. "All right, Indigo."

"All right, Joe."

The formalities were completed, a rough and ready partnership formed. Indigo studied the sweep of the valley through the trees. "What would you do," he inquired casually, "if a tin-horn sport insinuated yuh was holdin' more aces than the law required? Yuh a-knowin' all the time this gent had a sleeve full o' said aces an' was jus' tryin' to initiate a argument for private purposes?"

Breedlove studied the matter at full length, likewise watching the valley below. "I believe I'd enter some sorta protest to the management. Nobody's got a call to be ill-mannered."

Indigo seized upon this with a show of eagerness, as if it had justified his acts. "That's jus' exactly what I did. But I didn't kill the guy. Nossir, I aimed high an' to one side. If he died it was because of his own weak constitution an' none o' my fault. Why should they blame me because some gent went into an argument with impaired health?" Then his manner and tone changed. "You skin out of here, Joe. Them bloodhounds are back-trackin'. They'll reach here in no time."

Breedlove also had seen the dust cloud growing out of the west. He slipped from the saddle and motioned to Indigo. "Hop aboard. Skin out. When the storm's blown over come back."

"Hell, no," objected Indigo. "Those guys ain't civil."

"They don't know me from Adam," said Breedlove. "I'll say you ambushed me and took my horse. Hit over toward that broken top and I'll steer 'em north."

Indigo gave Breedlove one quick glance and swung up. "All right. But I'll have an eye on 'em. If I see you bein' led off in chains I'll turn this country to cinders."

"A soft answer," smiled Breedlove, "punctures many a bloated temper."

"Mebbe so," was Indigo's dubious reply. "I ain't never tried it" Then he was up the hollow and out of sight. Breedlove moved half along the slope, buried his gun beneath a flat rock and settled back to smoke in peace.

THE posse came upon him somewhat sooner than he had expected. In fact it was just three cigarettes later that he heard a rustling noise to his rear and an abrupt command to elevate his elbows. He complied, though not in silence.

"Pull in yore neck," he advised the unseen gentleman. "Can't a man study nature without interruption?"

Men dropped into the depression from various angles. Indigo Bowers had called them beetle-faced and it would have been difficult for Joe Breedlove to have improved on the term. Foremost among these pursuers was one who had a pair of excessively bowed props and a bull voice. He aimed a question at Breedlove in a conversational tone, yet the echo of it fled among the trees and filtered down toward the valley.

"Where's the leetle sawed-uff runt with the trouble-huntin' face?"

"I wish I knew," murmured Breedlove, rolling still another smoke. He jerked a hand to the north. "Last I saw he was foggin' up thataway. If you find him jes' kindly return my horse which he appropriated."

They were not to be easily convinced, these fellows. Breedlove saw it in the manner they studied him. "What brought you this way anyhow?" demanded the full voiced one.

"I come from Prairieville," explained Breedlove in a mild tone. "Saw a buzzard circlin' over here an' thought I'd investigate. I walks, myself into a trap."

"Well," ruminated another, "that ain't no lie. I saw that buzzard. Didn't I tell you, Ike? We should a' left that damn trail an' hit here first"

"Was the gent badly wanted?" asked Breedlove.

"He shot an' killed the best stud dealer in the county, brother. It ain't a thing to whistle off. No, it ain't. North, yuh say?"

"Uhuh."

They collected in a group and filed toward the top of the bowl. "Say," demanded Breedlove, "where's the nearest rancho? I got to get another horse.'

"Cloverleaf—three miles south." Then something seemed to strike the leader and he turned, bringing the whole crowd to a halt. "You don't seem very doggone put out about it. Looks like a trick to me."

"Shucks," grinned Breedlove, "all the snortin' an' pawin' in the world won't do no good. I ain't worryin' none. You boys'11 get that horse for me, and the gun likewise which he took. I'll collect 'em in Canyon tonight. Treat the horse gentle."

IT WAS not so much the words he said, but the manner in which he issued them, soothingly, authoritatively. They disappeared over the bowl and in a moment he heard them riding away. Nor did he bother to rise and watch them immediately. Not until the sinking sun found him out and made that particular haven uncomfortably hot did he move. Casually, he strode upward and swept the little stand of pines. Satisfied, he sought another spot and waited until he heard hoofs drumming. Indigo swept into view riding the borrowed animal and leading another. Quite in silence as if this were only a minor detail of the day's chores, the two of them went about their business. Indigo saddled his new horse, tarried a moment to look at the dead animal and pressed his lips tightly together, avoiding Breedlove's eyes.

"Shore a good pony," he grumbled. "If this brute's half as saddlewise, I'm lucky."

Away they traveled, and it was a little curious the way the leadership seemed to fall quietly upon the tall, serene man's shoulders. Indigo merely said, "Now where, Joe?" and fell to meditation.

"When in doubt," reflected Breedlove, "lead for the stummick. We'll aim straight tords Canyon, I reckon. What's on yore mind?"

"Me? Oh, Im headin' for the Box U like I said an' get me a job. Where you go-in'?"

"Bound south," and there was a trailing note of lonesomeness in it. Indigo looked sharply at his new partner.

"Mebbe there'd be two jobs at the Box U," said he gruffly.

"I misdoubt I could put a mind to work right now. I'm an old horse, needin' some open range for a spell."

An interval of silence. The sun sank and the world for a time was ablaze on the western summits. Then a swirling blue dusk enveloped them and the autumn chill nipped their bones. Indigo seemed to be feeding on his injuries. He swore in lilting, honey syllables. "I'd shore like to level that town right down to the grass roots. Thunder, they's a lot of hog-fat hombres there which I'd like to send squealin' for shelter."

Breedlove chuckled. "Spunky cuss, ain't you?"

"Me? Say, Joe, it's shore funny how I ram my smeller into trouble. Allus been thataway. But I shore can't stand to have rannies pulled on me."

"Providence," mused Breedlove, "has a way o' takin' care o' all that."

"Providence has shorely been squattin' on me the las' two days," grunted Indigo.

"Well, Providence has got to sit an' rest sometimes," agreed Breedlove. "But she rises again. She rises an' the world shines bright."

"Now ain't that restful," murmured Indigo. There was irony in it but it was the kind of irony covering admiration.

Thereafter no more was said until the glimmering lights of a town met them. They had traversed a ridge, climbing higher and higher. The valley on their right puckered together and dived into the narrow recesses of a hill and in a little while they discovered themselves looking directly down on the house-tops of Canyon. Canyon the wayward and the headstrong. Joe Breedlove studied it, his chin resting on shirt front. Indigo stirred, saying with no great enthusiasm, "Well, amigo, I guess I'll strike east from here. Box U thataway, jus' acrost the State line."

"Ain't had nothin' to eat, have you?" interposed Breedlove. "No, shore not. You make a cold camp here while I go down an' rustle a little grub."

"Say, yuh can't walk them premises peaceable," objected Indigo. "They'd spot yuh. The posse is mebbe back by now. And I don't misdoubt but what the rancher I got this hoss offen has come in with his yarn. Yore gummed up with the same sheep dip I am now."

"Well, I don't believe the posse has got back. They seemed out for blood an' bent on ridin' till they found you. Anyhow, I don't owe this town money and I eat my supper regardless of any barrel-bellied star-toter. Should worst come to worst, I can talk 'em peaceable."

"Yuh got a lot to learn about Canyon," prophesied Indigo. "I'm waitin' here, then. Should I hear trouble, I'll fog after yuh."

"Trouble," philosophized Joe Breedlove, "is a delusion which only the wicked fear. Hang to your vest buttons, Indigo. Ill tote back some chuck."

He started down the trail but returned to dismount. "I'll leave the horse here. Safer if the sheriff, or whatever he is, should pop in." And he vanished in the shadows.

IT WAS a steep pitch and let him down quite abruptly to one end of the solitary street through the town and the canyon. It was like all other cowtowns in its essential features, yet, since it had its back to the hills it drew many queer characters, many fugitive characters into its confines. Breedlove noted them here and there as he marched straight upon the restaurant; noted, too, that although the evening was young, considerable noise drifted from the half dozen saloons on either side of the street.

At the same moment he was inspecting his surroundings, others were inspecting him from odd corners. He was a cowpuncher in every muscle and gesture, yet a cowpuncher without a horse, a circumstance bound to attract curiosity. He felt this scrutiny and, as he slid to a stool and ordered a double order of steak, he understood the justness of Indigo's comment. Lawless Canyon might be; nevertheless the town seemed to scan its guests with something more than casual attention.

"Takes a can-opener to get in an' a crowbar to get out," he murmured much later when the weary and slightly acid lady of the establishment slid sundry platters toward him.

"What was that?" asked the lady, sharply.

"Merely remarkin' that this shore was a han'some piece of cow," he hastened to assure her. Such a thing as a napkin failed to exist but a month-old paper lay within reach and he took this, making a huge sandwich of the extra steak and several pieces of bread. He wrapped it well, noting the lady's furrowed brow upon him. "I'll be a long ways from here by breakfast," he explained.

She lifted one scornful shoulder. "Another gent hidin' out. Say, there's more men up in those hills than down here. What's your shyness?"

He winked expressively, laid a dollar on the counter and gathered his sandwich. Still she seemed unsatisfied. And when he had finished his meal and was about to go, he dropped his voice low. "Lady, breathe it to no livin' soul. I'm the man that struck Billy Patterson!"

"Kill him?" she asked, matter of fact.

He was out of the place, chuckling softly. It had been no more than a matter of five minutes, yet traffic on the street had increased. More horses were tethered on the racks, more noise floated from the saloons. He shook his head and headed out toward the top of the hill, not at all sorry to be quit of Canyon. Yet it was not to be so easy a retreat. Hard by the restaurant, in a particularly deep patch of darkness, a hand fell lightly on his arm and a woman's voice, moved by distress, spoke.

"I—I saw your face by the restaurant light. I know you are honest! I've got to have help!"

That stopped him as if a lariat had tightened around his shoulders. He could not see her, not even that lightly detaining hand. It didn't matter. Her voice decided him on the spot. So he stuffed the sandwich in his coat pocket and answered promptly. "Ma'am, it is done."

"My father is in the Blazing Star! They've got him at a poker table and they'll never let him go until they've broke him! I've waited and waited with the buckboard! Not a man will help! He's got all our cattle money! You'll get him for me? A heavy man with a white goatee and a white Stetson. The name is Henry Allen. If you'll only get him out of there—"

"It'll be the matter of a minute, ma'am."

Her answer was vehement. "You've got something to learn about Canyon."

"Education," he remarked gravely, "can never start too late. Wait here."

He walked leisurely toward the mentioned saloon, reflecting that twice that evening he had been told there was still something to learn of this town. And for all his apparent unconcern with the girl, he stood by the swinging doors and pondered a moment. "I'm a man of peace. Shore, shore. But where kind words fail " His fingers brushed the butt of his gun. "Where kind words fail, Providence and a little main strength must finish the job. Henry Allen, you old dodo duck, ain't there no sense in yore head?" With which he pushed through and stood in the brightly lighted bar-room.

FOR all the noise, the place was not crowded. A few were at the bar, a scattering number lounged around restlessly, and no more than a dozen played at the tables. Breedlove saw Henry Allen's white Stetson and goatee at once, pondering over cards. But he did not make the mistake of going directly to the man. First he filled his glass and drank, meanwhile eyeing the place with a mild interest. The table at which Allen sat held but three players and to Breedlove's shrewd mind it was evident one of those players stood as nothing much more than a dummy. Allen was the sheep they were fleecing and the third member, a professional gambler in every feature, seemed to be doing the job cautiously, painlessly. Breedlove deserted his glass, slid casually to the table and took an empty chair.

Sharper than a serpent's tooth is the bite of a man unwilling to be rescued. Allen raised his flushed, half-angry face to the newcomer. "Three-handed game, friend. Pick another table."

"Well, if I can't play I can look in," said Breedlove amiably. The gambler's impassive face swept the newcomer and there seemed to be a wisp of dry humor in the opaque eyes. Here was a man who new the ins and outs of the world, one who returned that glance with shrewd, tolerant eyes. They understood each other without saying so much as a syllable.

As for Henry Allen, he was just another heavy-handed fool goaded to recklessness by his losses. What little he knew of this game of games—the element of timing, deception, false gestures, the ability to drift through bad hands and plunge with good ones—all this knowledge had deserted him. In the hands of the skillful professional he was a bull plunging at the red cloth. Perhaps he knew he was playing great odds against short ones, certainly he had torn more than one hand to pieces and called for a fresh deck. The litter of such was on the floor by him. Still he stumbled on, obsessed by that fever which forever leads to ruin.

Breedlove, sitting idle, grave as the sphinx, knew it would never do for him to attempt to persuade the man to give up and go back to his daughter. As well try to dam Shoshone Fails with his hands. The gambler's long, slim fingers dealt around the board swiftly and Breedlove's eyes watched them jealously between lowered lids. Crooked cards, naturally. But the professional hardly had need to be crooked to trim this blundering, stubborn Allen hombre. Now wasn't it a problem? Wryly, he remembered saying to the girl it would only be a moment.

Looking up and around he saw two or three stray characters leaning against the bar, paying particular attention to him, Their faces seemed vaguely familiar. Were they part of the posse or not? It seemed likely. A second glance sometime later revealed that one of these had left the saloon. The gambler's eyes had lifted toward them, fluttered, and dropped again.

"Devious," stated Joe Breedlove to himself. "Devious but plain. Should I make a move, where would I be? Yeah, where would I be?"

"Little ones, full up," droned the gambler and spread deuces on trays across the green cloth. Allen glowered at the hand, dropping a broken straight. Breedlove could hardly repress clucking his tongue. The fool had tried to bluff it out with the game running against him and the weight of the chips on the other side. What he didn't know about human nature was ample.

ALLEN'S own pile was down to a half a dozen blues. His purple face sagged and he threw the weight of his shoulders forward, resting on the table as if seeing bankruptcy in those fanwise pasteboards. He ran a shaking hand across his disheveled hair; the game faltered and the gambler's fingers were shoving a fresh pile across. "Luck changes around midnight, mister. A hundred more?"

Breedlove swept the room with a flashing gaze. Two big lamps behind the bar, one in the middle of the room. And that bull-voiced leader of the posse just sholdering through the doors. It looked for a moment as if Allen was going to back out and call it an evening. Breedlove's muscles hardened. But the gambler's voice was persuasive and Allen reached into his pocket, dragging out a pouch that clinked with the unmistakable sound of gold pieces as it struck the table. It was still a well-filled poke. "Why, I reckon—" began Allen, plucking at the draw-strings.

Breedlove's hand swept across the table, closing like a vise around that pouch. His mild voice entered the proceedings.

"Henry, if it was yore own money, I wouldn't say a word. Not a word, Henry. But seein's as I grubstaked you and got a sorter half interest, why I think I'd ought to be paid afore you go gamblin' any more."

Allen was half out of his chair, crimson and outraged. He had no gun or it would have been drawn, Breedlove was sure of that. "Why, you damn' meddlin' outlander, leggo my pouch or I'll—"

Breedlove showed a pained and steadfast face. "That's right! Treat me as a stranger to save yore own pride. I don't care about that, Henry. You been actin' queer to me ever since I got to town. Nev'less, I'm demandin' my share afore you lay another bet."

"Your share!" yelled Allen.

"Come outside, Henry," entreated Breedlove. "We'll talk it over alone."

The gambler had scarcely moved a muscle, yet a point of light flickered in those drab eyes. "Smooth, quite smooth," he said, very quietly to Breedlove. "But what's your game?"

"Keep out of it," warned Breedlove, slashing at him with the words. For the first time during the scene a deep and slumbering temper flared in him. It shuttered across the serene face and left it harsh, like so much granite. "Keep out of my play." Once more he turned to Allen. "Let's go outside Henry and talk this peaceable. I ain't goin' to make a fool of you or myself afore strangers. Come on."

The situation had drawn dangerously tight. The gambler seemed frozen in his chair. Every other man in the house was silent and by the bar the same three whom Breedlove had seen before, were standing with a tell-tale negligence. He heard the bull-voiced gentleman cruising slowly toward the table. There was dynamite in the Blazing Star; well he knew it. He had moved under poor conditions, yet it was the only way open to him. By usurping Allen's poke he had made it a quarrel solely between the elderly man and himself, a quarrel in which others could not legitimately come. At the same time he hoped Allen might catch on and might use it as an excuse to retreat. Once again he urged his point. "Le's go outside, Henry, I'll give it back then. Come on."

But Allen was not of the kind to make a good bargain of a bad one. He shook his fist at Breedlove. "Drop that pouch, you mangy cur! Somebody gimme a gun! Have I got to be held up in sight of the hull town? Gimme a gun!"

So the man was inviting others to share his quarrel. Breedlove, moving with deceptive slowness, rose and turned about, confronting the bull-voiced one. The man was a sheriff well enough; the star hung conspicuously from his vest. His oval face was aflame with suspicion.

"Seems every time I see yuh, friend, yore mixed up in difficulties. What you do-in' now?"

"Find my horse, Sheriff?" countered Breedlove.

HE TOOK a step backward. Nobody stood behind him now. He commanded a view of every soul within the place. Three lamps, two behind the bar and one to his left hand. Well, he could get the pair over the bar before anybody drew. Still, it wasn't just his fight. He had to get that cussed pigheaded loon safely from the scene.

"Yore horse?" boomed the sheriff. "Hell, I misdoubt yuh ever had a horse! Don't tell me yuh ain't in with that bantam rooster! Where's he holin' up now?" And then he saw Breedlove's gun. "Thought he'd took yore wee-pon? Oh, no, yuh don't git away with that yarn! Say, was yuh tryin' to stage a holdup under our smellers? Drop it, fella or I'm bearin' down on yuh!"

"Listen," began Breedlove, smiling his famous smile. All the benevolence and the charity of the universe beamed on his bronzed face, "Henry says he don't know me. Well, natcherlly he don't want to appear like a fella gamblin' off his friend's money—"

"You lie!" shouted Allen. "You lie! Pin him, Sheriff! It's a bold-faced holdup!"

"Drop it!" was the sheriff's brittle order. "Or—"

Well, now was the time if ever. The philosopher must become the man of action. Breedlove, still smiling gently, swept the whole group. His right arm for the instant remained immovable, but the fingers splayed out slightly and his head dropped a trifle. Allen was speaking rapidly and with increasing rage. The swinging doors burst wide open and a man popped through, hatless, excited.

"Say—say, you hombres! Git to hell outen here an' fog down to Minnick's deserted stable! It's afire! Wind suckin' the flame right tords town, too! Come on or we wunt have no roostin' spot!"

"Providence," murmured Breedlove lazily, and his smile grew less rigid. The sheriff swayed uneasily on his toes, but the rest of the onlookers hurled themselves toward the street, bowling over tables on their way out. A shooting scrape was not uncommon to Canyon, but a fire coming to a town of scant water and tinder-dry houses, touched them vitally either as a matter of entertainment or as a sterner enemy to be fought. So they fled and presently as the blood glow of the flames seeped through the foggy windows of the saloon there was left but the gambler, Henry Allen, the sheriff and Joe Breedlove. The sheriff, off guard, dropped back on his heels and turned his head ever so slightly. "Damn!" he grunted. Joe Breedlove was chuckling. Light glimmered along the barrel of his drawn gun. "Turn about, Sher'ff. Providence rises an' the world is filled with light." He captured the official's revolver and nodded at the gambler.

"This ain't yore quarrel, remember."

The gambler shrugged his shoulders. "Your pot, friend. Smooth, very smooth. I take off my hat to you."

"Tell this man—" pointing to Allen— "somethin' he ought to know."

"Why should I? Just another fool after easy money. Why should I?"

BUT Breedlove looked quite steadily at him, as one worldly wise man to another. "No, you ain't that kind. His daughter's been waitin' out there three hours for him to bring home the year's earnin's."

The gambler's face lost a little of calm. The stack of gold he had won from Allen was piled neatly behind his chips. He swept it up and thrust it at the older man, adding a few sharp, curt words. "You infernal idiot! Don't you know better than to play another man's game? If you ever come here again, I'll pluck every hair off your billygoat face!"

"Out the back door," said Breedlove. Allen, holding the returned money in one fist walked across the room with sagging steps. The sheriff never moved, but the gambler threw up an arm as Breedlove stood framed in the rear entrance. "Some day, come back," he called. "I could learn a trick from you."

Breedlove smiled and closed the door. Never saying a word he pushed Allen down an alley and to the front street. Toward the east end of Canyon the stable roared in flames, lighting the street plainly. But the men running by had no time for him and he reached the girl and silently passed over the money pouch to her. "Keep this in yore own hands, ma'am. Even so, I think yore daddy won't fondle the pasteboards for a while."

She was quite fair and when he saw how her eyes glistened unaccountably he was forced to turn his head a little, hearing her words as from a great distance.

"Slim—I knew you were an honest man. I'm thanking you."

"I remember a girl that looked like you once," he murmured. "She was shore some lady." And then he had ducked back in the alley, traveling swiftly. He climbed well around Canyon and it was perhaps a half hour before he reached the top of the bluff again. He found Indigo lying flat on his stomach, head overhanging the town; and Indigo was grinning from ear to ear.

"Ain't it purty?" cooed the little man. "Oh, ain't that a fine sight? Nineveh an' Tyre—they don't compete. I wisht a spark would carry over an' make a real bonfire. Did yuh get a snack, Joe?"

Breedlove passed across the beefsteak sandwich and sat Indian-fashion while his partner ate. "All I'm needin' is a napkin now," sighed Indigo, "to make it a Roman feast. Amigo, we'd better pull freight afore they git time to think."

"It's my belief, likewise," said Joe. And they mounted and rode out of the aura of light, traveling upward and eastward until darkness cloaked them.

"Providence shore disposes of a lot o' things," murmured Breedlove.

"Providence—hell!" snorted Indigo. "I set that shebang afire. Knowed yuh was in trouble on account of the time yuh took. So I though I'd give 'em somethin' to diversify their minds." He snorted. "Providence! Huh!"

"Well, Providence an' a little personal aid, then," amended Breedlove, smiling in the shadows. But when they came to a forking of the trails the smile had disappeared. He drew up and sat silent. Both of them understood well enough that here was the parting, yet both of them seemed at loss for words.

"Bound south," muttered Breedlove, that trailing lonesomeness touching the words.

"Mebbe there'd be two jobs on the Box U," suggested Indigo gruffly.

"No, I'm an' old horse needin' pasture."

"Well, so long Joe."

"Good huntin', Indigo."

Another moment they tarried. Then darkness dropped between them like a curtain and they had only the sound of each other's horse striking the rocks along the way. In time that died and they were traveling their lone trails.

Breedlove rode leisurely, eyes fastened to the blue ceiling above. "Spunky cuss," he muttered. "I guess I must be gettin' old. Seems like the taste of things is a little flat nowadays."

PRESENTLY he left the pines to the rear and dropped sharply downward. Ahead rustled the waters of a river shallowing up at a ford. Across the way was another State. And southward there would be still more wide prairies and still more miles to travel alone. He pushed ahead, somber and meditative. "Indigo will be shakin' out his bed-roll tomorra' this time. Oh, well—"

There was a small echo directly ahead and as he pushed to the brink of the ford a shadow barred his path. A voice floated up. "Now who would that be, anyhow?"

Breedlove straightened. "Indigo? Thought you was a-goin' to the Box U?"

"Well—"a trifle angrily—"ain't I on the right trail, I want to know?"

"No, I guess you circled around the hill on the wrong trail."

Silence. A half-sheepish rejoinder.

"Shucks, so I musta. Well—"

Breedlove heard Indigo's horse breathing as if it had been put to a hard run. He smiled sweetly in the darkness, feeling immeasurably better. Still, he held his peace, knowing it to be a ticklish moment. Indigo spoke again, very fretful. "Well, wouldn't that singe the hairs on an asbestos cat? How could I have got off like that? Shore foolish."

"I've done it lots of times in unfamiliar country," reassured Breedlove gravely.

"Shore, that must be it Well—"

"I imagine they ought to be a right good campin' spot acrost this stream."

"Now, I believe there would be," said Indigo with alacrity. "Oh, hell, I ain't goin' to back track. Box U can wait."

"Mebbe some grazin' might help you, too," said Breedlove, the smile broadening.

"Lead on, Joe."

"Bound south," murmured Joe and pushed into the stream.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.