RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

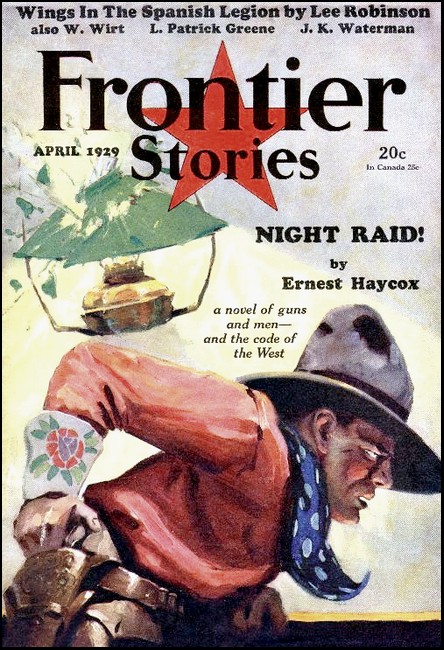

Short Stories, April 1929, with "Night Raid"

"Mind your own business" was the Golden Rule of the rangeland—the code to which big Joe Breedlove and salty Indigo Bowers clung through thick and thin. Just once did they violate it—but when they did, pistol-fog rolled like night-mist across the Elkhorn range, and the roar of guns was like summer thunder

IGHT had come again, a soft desert night that damped the intolerable heat of day. In another half-hour the small campfire gleaming on the edge of the gravelly creek would be a grateful barrier against the sharp, still cold. Overhead swung the infinite canopy of heaven, its metal-blue expanse shimmering with stars; far and low on the horizon the moon hung at a crazy angle, a thin-edged crescent that gave no light. A thousand miles of desert and mountain marched to this solitary outpost of man and seemed to stop, while the bark and whine of distant coyotes and the murmuring of the creek alone broke the spell of silence. Sage smell was in the air; the smell of bacon

and coffee had not yet quite gone. Two horses browsed beyond the rim of light, picketed. Blankets were down, and upon them stretched two weary travelers who had ridden a good many leagues in search of rest and surcease from the carping cares of men. Indigo Bowers and Joe Breedlove camped again.

No two individuals could possibly have been more dissimilar. Indigo was short and thin; his pointed, saturnine face was homely beyond description. And as he sat humped over, staring into the flames, it appeared that he thought of all the sorrows and all the troubles the universe bequeathed its mortals. No ray of cheer broke the set pessimism of lips, no trace of humor leavened his faded blue eyes. Life, it appeared, was just one dirty trick after another. Which is to say that Indigo Bowers was in his usual frame of mind and in his usual state of health.

Joe Breedlove, on the other hand, was a tall and muscular man. The firelight gleamed along his corn-yellow hair and snapped in his hazel eyes. He was looking up—up to the stars, his body relaxed and his face mirroring the perfect serenity that was so much a part of him. Joe made friends easily, and once made these friends clove to him forever; there was a mellowness about him, a whimsicality that tempered all his acts and all his words. The world, according to Joe, was the only world available, therefore why fret?

HE DROPPED his attention to the gloomy Indigo, fine wrinkles sprang around his temples. "Providence," said he in a voice that plucked the strings of melody, "sure thought about man's comfort when it created night an' shadows. Me, I like shadows. It's all the same as takin' a bath after a hard day's work."

Indigo emitted a rasping sound of dissent and his cigarette drooped from a corner of his thin lips. "Yeah? There you go again with that doggone romantic imagination o' yours. Seems to me Providence made night because it's ashamed o' the ant-hill it created down here. Did you ever see anything more forlorn an' useless as the country we been ridin' through lately? I'm so cussed full o' sand I grate every time I move. I'm scorched like a kernel o' popcorn. Been lookin' at sagebrush an' distance so long I got a perpetual headache."

"Well," admitted Joe, mildly reluctant, "it's a mite sparse at that, but it's sure fine grazin' land for cows."

"A cow don't know no better," argued Indigo. "Personal, I don't like this land. A self-respectin' buzzard wouldn't lay an egg in it. How long we been on this so-called journey o' rest anyhow?"

"Six weeks barrin' two days," said Joe.

"Yeah, an' how much rest have we got?" Indigo grew querulous. "It's funny how folks pick on us. Nothin' but trouble, nothin' but scraps. If ever we back-track we sure will have to pick another route. Six towns in a row is layin' for our hides. Rest—huh!"

"I'm a man o' peace," drawled Joe "I don't like to fight. If you didn't pack a temper full o' poison "

Indigo stilled his partner with a gesture of a skinny arm and raised his somber countenance against the night. His nostrils dilated slightly, like a hound keening the wind. "They's trouble somewhere out there. I know it. Sounds to me like them coyotes is japin' us. I wish folks wouldn't pick on me."

Joe met this with a skeptical lift of eyebrows. His partner was like a bantam rooster strutting around the arena. Indigo's past life consisted of successive chapters of violence. He claimed he wanted to be left alone yet it was always noticeable that when in the proximity of a fight he grew strangely restless. It only took one small word of invitation to bring him into the tangled affairs of other people. Many men had been deceived by Indigo's wisp of a frame; when he moved, he moved like dynamite, leaving destruction in his wake. And no amount of logic ever could convince him that he was other than a mild and inoffensive creature who had been unjustly picked on. He stirred on his blanket, the washed-out blue eyes darting around the rim of light.

"Just the same, they's somethin' goin' on around here I don't like."

OE BREEDLOVE never moved, yet there was a slight tightening of his big frame. A sage-bush rustled out beyond. Something stirred, the gravelly ground marked a body passing across the darkness, and the horses became uneasy. Both partners became unnaturally still. Out of the shadows marched a rawboned man with the russet beard of Judas and eyes that were brilliant black; a burly creature coated with dust and a general flavor about him that augured a shattering of the commandments. He squatted by the fire looking swiftly from partner to partner. "Howdy, gents!"

"Huh," grunted Indigo, visibly annoyed. The fellow's approach violated all etiquette. Indigo believed in etiquette on the range.

"Nice evenin'," stated Joe Breedlove, mildly. "Stir up the fire."

"I ain't cold," said the newcomer and relapsed to a full silence.

It was up to him to announce himself and the partners waited, each staring into the flames. Joe Breedlove appeared to be in a deep and profound study; the placid benevolence of his face never changed. It was otherwise with Indigo and with each passing moment he grew more and more restive until it seemed he was about to suffer an acute attack of indigestion. Then there was another sound beyond the fire's rim and a second newcomer hitched into the light and squatted by the blaze; he was built like a pole and his jaw was nearly as long as that of a horse. Once more the partners were inspected in a swift and sidling manner.

"Howdy, gents."

"The same," murmured Joe and casually draped himself in a manner that left his right arm free to swing. Indigo muttered and morosely held his peace. A moment later he flung up his head to find three other strangers marching out of the night. One by one they dropped to their haunches, none of them bothering to pass a greeting. Indigo looked across the flames to his partner, and Joe's left lid fluttered. The five visitors were as grave as redmen; the one who owned the russet beard looked around the circle and announced succinctly, "It's them all right"

"Yeah, I reckon," observed the gentleman with the horse jaw.

"You'll excuse the manner o' droppin' in," said the red-bearded gentleman to Joe and Indigo, with just a trace of deference in his words. "But we wasn't shore it was you boys. Elbow Jim is the only one which ever saw yuh an' he's laid up in town with a lot o' concussions where a hoss kicked him. I guess he's out of it for some days. Anyhow we sorter hung back an' watched yuh sashayin' acrost the country today. Elbow Jim said it'd be a big man an' a leetle man, so's we waits to get a good look."

It never took much to soothe Indigo's feelings. A sort of an apology had been offered and he accepted it with magnificent forbearance. "That's all right—that's plumb natchral."

"Well," went on the one with the red beard, "it was Elbow Jim's idea to write an' ask yuh to come down here. He had a lot o*' confidence in you boys. Mebbe he told yuh all about it in the letter?"

Here was a situation. Indigo, never a great hand at deception, kept still. But Joe waved an arm. "I reckon he didn't say much. A letter, you know, is sorter public."

"That's right," agreed the red-bearded one. "Elbow'd be pretty secret. Well, it was his idea. But since he ain't here to unravel it I guess we'll have to go on without him. Me, I'm Bo Annixter. He's—" pointing to the fellow with the horse jaw, "Shirtsleeve Smith." And Bo Annixter went around the circle, calling names. The partners gravely nodded.

"The point is," proceeded this red-bearded Annixter, "we're plumb able to rustle our own critters, but lately the county's sorter tightened up. They got a sher'ff who's watchin' the railroad. We had a gent who took our stuff an' got it to market for us. Well, he quit—scared out. Reckon he's made all the money he wants so he's figgerin' to be an honest gent from now on. Which leaves us up a tree."

"The country," opined Indigo, "ain't what it used to be."

"Now you said somethin'," agreed Bo Annixter. His black eyes stabbed Indigo and passed on to Joe, leaving Indigo dubious. This fellow with the red foliage looked mighty tough and so did the other four rustlers. Doggoned tough.

"That's why Elbow wrote you boys. We figgered we'd rustle the cows an' run 'em to the county line. There's where you'd take 'em an' fog 'em to yore hangout. Elbow said yuh allus had a place to sell."

"Well—" murmured Indigo and waved his arm vaguely.

"Sure—sure," interposed Annixter hastily. "We ain't askin' nothin' about yore location. Jus' take 'em an' get rid of 'em. We split fifty-fifty. That's fair enough, ain't it?"

"That's downright handsome," agreed Indigo, almost with enthusiasm.

"It ain't everybody we'd trust like that," said Annixter. "But Elbow said you was four-square gents. So that goes with us."

"Our word," declared Indigo, rearing up, "is good as gov'ment security."

LL the while Joe Breedlove had maintained silence. Indigo, meeting his partner's attention, was suddenly aware that he talked too much.

And, upon a second observation of the five rustlers—seeing them sitting around so watchfully, and seeing the firelight slant across their hard jowls—he decided he had played the situation a little too far.

"It's like this," went on Bo Annixter, turning to Joe Breedlove. There was something about the golden-haired man that always attracted attention and respect. Inevitably he was looked upon as the leader of the pair; perhaps it was his smile, or the lazy way he carried himself, or the unbroken serenity of his countenance—at any rate when men dealt with the partners they soon came to ignore Indigo. Ordinarily Indigo would have resented such a thing, he would have risen upon his haunches and launched his defiance. But with Joe trailing beside him it was different; deep down in his heart Indigo admitted Joe to be the better head. Which was saying much for Indigo.

"It's like this," repeated Annixter. "They's the Elkhorn outfit five miles from here. Old man Stovall runs it. They's only five hands on the place. We ain't ever touched it, but now's the time. Part o' their summer range is right near the county line an' they ain't but one hand ridin' thataway. See? Shucks, it's easy. All clear?"

Joe's head bobbed slightly, whereupon Indigo began to worry. He depended always on Joe to get them out of trouble—and here was Joe drifting into stormy waters.

"Fine," said Aunixter, and slapped his thigh. "Then we might as well get at it tonight."

Indigo bent forward to poke the fire and in so doing got a chance to look well at his partner. Joe appeared never so placid as now. By and by he stirred.

"How far is that Elkhorn ranch-house?" he asked, mildly.

"Five miles due south."

More silence on Joe's part. And this very silence plainly increased Annixter's respect. "Of course," said the man, "mebbe it ain't very big potatoes for you boys. Elbow says yuh handle consid'ble beef. Still, they's a neat profit. If yuh want, yuh can sit right on the county line an' we'll rustle 'em to yuh."

Joe squared his shoulders. "I guess not tonight. My partner and me always like to look a layout over before we do business."

"Shucks, it's pie," protested Annixter, evidently not liking the delay.

"Shore," agreed Joe. "But it's a rule of ours. Never pays to make a pass in the dark. That's why we're still free gents."

Annixter silently debated; the rest of the rustlers waited. There was something so taciturn and so calmly confident about them that Indigo, as hardy a gentleman as he was, grew nervous. The sooner he and Joe were out of this the better. "Yeah," said he in a dry voice, "it's a habit o' ours."

"All right then," agreed Annixter. "We'll sleep on it. Run over t'morra an' look. We'll do it that evenin'."

The rustlers rose and went back into the darkness. Saddle gear jingled, horses moved into view; and presently the whole five were back with their blankets, bedding down for the night. Indigo, scratching his head, felt the sweat trickle down his cheek. And it made him mad. The fire died and the camp slumbered, though Indigo's rest was broken by the memory of Annixter's beady eyes.

T DAWN the partners were up and away, leaving to Annixter and the other four the assurance that they would be back at the same rendezvous around noon. Joe was profoundly buried in one of his meditative spells and Indigo kept the silence for a good quarter of a mile, or until he looked back and saw the rustlers streaming across the land in another direction. Then he could hold himself no longer.

"Who started this doggone deception, anyhow?" he demanded.

"I'd be obliged for the information myself," said Joe, rousing. His mild glance fell upon Indigo with more than a passing interest. Indigo rose to his dignity.

"Don't look at me like that. I didn't tell 'em we was the gents they wanted to meet. Well, not exactly. Why didn't you speak up an' say it was all a mistake?"

"Why didn't you?" countered Joe, rolling himself a cigarette and studying the horizon with a far off gaze.

"I thought about it," admitted Indigo, "but judgin' from appearances it looked to me as if the news might've irritated 'em some."

"That was my conclusion likewise," agreed Joe. "And what's the use of disturbin' folks' feelin's?"

"Well," summed up Indigo, "we're supposed to be a couple of high-class rustlers from the county to the north. Must be awful high-class, the way they trust us. An' we're supposed to be friends to this jasper Elbow Jim who's laid up with a belted coco. What gets me is how quick they figgered we was somebody we ain't. Awful careless."

"I sorter suspect," put in Joe, "that we camped on the spot the two parties was to meet. Indigo, wouldn't it be real interestin' if them two real rustlers should arrive about now, or if this gent Elbow Jim should appear on the scene?"

"I dunno," muttered Indigo in apparent despair, "why people should pick on us so. I don't see nothin' interestin' about said eventualities. All I see is a lot o' trouble. Told you so last night."

Indigo observed that Joe had a tight and familiar look upon his face. It meant profound thought and Indigo felt the chill of anticipation. It couldn't be that this easygoing partner of his— No, Joe never horned into a strange game. Still, as a kind of feeler, he put forth a general statement. "The farther we ride an' the quicker we ride the sooner we'll be out o' this mess."

"That sounds sensible," murmured Joe, still engrossed in his thoughts.

Indigo was vaguely disappointed. "Mebbe we should stop at the next town an' tell the sheriff." But in a moment he answered that for himself. "No, it wouldn't be none of our business, wouldn't it? Same as spyin'. But, say, how about droppin' into this Elkhorn outfit an' passin' a hint?"

"That ain't much different from tellin' the hounds o' the law, is it ? Why butt into somebody else's affairs? It's their game, not ours."

Indigo rode in moody silence for a mile before muttering, "I guess it's none of our business."

Joe had no answer for that. Indigo studied his partner surreptitiously and couldn't quite get a perverse idea out of his head that the smiling and debonair Joe was still on the rack of indecision. At the end of another ten minutes he repeated his remark. "I guess it's none of our business."

"That's right," declared Joe, as if he'd come to a decision. "We ride."

"Oh, hell!" snorted Indigo

Joe grinned at his partner. "I thought you was tryin' to avoid any more trouble?"

"Well, but look at it," grunted Indigo. "It seems sorter stinkin' mean to me. There's that old gent who prob'ly don't deserve no misfortune. There's all them nice beeves—Joe, it don't seem right."

"Yeah, and there's all that trouble to fiddle your feet in," countered Joe. "Why don't you speak the real reason?"

Indigo refused to answer. He proceeded with a kind of smouldering excitement in his eyes and a feeling that his partner was wholly unreasonable and entirely too cautious. He knew as well as any man of the range could know that the first law was to mind his own business and not to tamper with another's quarrels unless definitely asked. Still, it seemed to him a bet was being overlooked.

P FROM the distance rose a ranch-house surrounded by corrals and outbuildings and a scattering of cotton-woods. Joe studied the scene between half closed eyes.

"I guess," said he with admirable casualness, "we'd better drop in an' get fresh water, hadn't we ?"

Indigo nodded, still resentful. They rode toward the house and presently reined in before the porch. Over the doorway spread an immense set of elkhorns. On the porch posts someone had imprinted the brand of the outfit with a hot iron—a miniature elkhorn. There was an ancient settee beside the door and in it reclined a man of about sixty with dead white hair and a florid face. He seemed quite hale and hearty, though a buffalo robe was thrown across his knees. Seeing the two partners he raised his hand by way of greeting. "Light and rest, boys."

"Why, thanks," replied Joe, eyes lingering a moment on the elkhorn brand, "but we're just passin' through. We'd trouble you, though, to show us the water. Canteens dry."

The man raised his voice, calling. "Oh, Julie!" Then he apologized. "I'd get up if I wasn't dead from the waist down. My girl will take care of you. Come from the north, eh?"

"Yeah," said Joe, only half hearing him. A girl stood in the doorway; a girl in her twenties with auburn hair and a rounding, supple body. The porch was shaded, yet it seemed to Joe Breedlove that the sunlight dwelt on her face. Gray eyes met and smiled at him.

"Julie," said the man, "take the boys' canteens an' fill 'em like a good girl."

Joe slid from the saddle, removing his hat. He collected the two canteens and passed them to the girl as if it were a ceremony. "Hate to trouble you, ma'am," he murmured, and again his voice plucked the strings of melody. Out of the saddle he made a fine showing, tall and muscular and self contained; a mature man who looked as if he loved life, who plainly had been through the world and seen it in many moods and yet could be whimsical and untouched by malice. The girl threw up her chin to study him, half grave, half smiling; just a trace of color came to her cheeks, then she retreated.

"Better stay to chuck," advised the elder man.

"It would be a command any other time," was Joe's courteous answer. "But we're just a mite rushed. Your range, I take it—your brand."

The man's chest filled. "You bet. Henry Stovall's Elkhorn ranch. Ask anybody in town about the name or the brand and see what they tell you. When I come here I used to ride herd on the Crow warriors. Long time ago. I've hired an' fired a thousand men—half of which is long dead. Now look. Four punchers and a foreman, a girl worth all of 'em and a paralyzed old duck better dead. But I bet I live to be ninety. Ain't that the way?"

"Who knows what the hole card is?" drawled Joe. "But it's tough not to be able to fork a horse."

Stovall's hands moved. "I'm a cattleman. Been one all my life. Be one after I die unless they make me shear sheep down in perdition. Does it hurt, not havin' a horse? I reckon yore man enough to know the answer to that."

"Well, you can still smell the wind," was Joe's grave answer, "an' hear the beaver-tails bellerin' out in the brakes. That's somethin'."

ROUND the corner of the house rolled a young man with dust on his chubby face. He was hatless, and jet-black hair curled around his head. Responsibility seemed to rest heavily on his mind, for he was very grave and he studied the partners with a quick, measured glance. Joe, who was a good hand at judging his own kind, decided that this chap was competent even if he wasn't much beyond voting age; and he returned the short nod with an amicable jerk of his own head.

"That calico is busted to work," said the youngster, to Stovall. "But he won't never be worth a whole lot."

"Let it lay," replied Stovall. "You boys are all a little heavy-handed with the ridin' stock. Takes an old-timer to deal with the cayuses." He turned his attention toward the parners again. "I could use some experienced hands. Want a job?"

"What for?" interposed the young man with just a trace of belligerence. "Ain't we got enough men already, considerin' everything?"

Stovall spoke soothingly. "All right, Slip. I know you're the foreman an' it's your place to hire an' fire. But I like old heads around me an' I ain't had none for a powerful long time. I'm repeatin'—there's a job for both you boys."

The girl came out with the canteens, in time to hear her father offer the partners work. A kind of alertness crossed her face, a touch of expectancy. Joe took the canteens and entirely by accident his big paw brushed her white hand. Thus they returned steady inspections until Joe dropped his head, smiling. "I'm obliged," said he and moved to his pony. Slip, the foreman, was still young enough not to be able to conceal jealousy; his lips tightened, he was not far removed from sullenness.

Joe climbed to the saddle; his eyes looked to the spreading elkhorns and again to the girl. "Thank you kindly, sir. But we've already got employment. We'll be ridin'."

The foreman disappeared back of the house. Joe and Indigo rode off. A hundred yards removed the tall partner turned in the saddle and raised his hand as a farewell. The girl still stood on the porch and her arm came up in reply.

All this while Indigo had said nothing. In company he seldom spoke, he always felt ill at ease and willing to have the more polished Joe take care of the amenities. But he missed nothing, he thoroughly inventoried the ranch and its state of prosperity in the few moments they had been by the porch. And he also had observed the glance the girl bestowed upon Joe. Well, many men admired Joe—and some women. How could it be otherwise? He turned to his partner and discovered that Joe was studying him quite soberly.

"News to me we had a job," grunted Indigo.

"I guess—" began Joe, and thereupon stopped. The youthful foreman came spurring toward them. The partners halted and waited till he came up.

"Didn't aim to be unsociable back there," he explained, still a little surly. "But the old man is losin' his grip. Think's he's better off than he really is. Always wants to hire somebody. You savvy, I guess."

"Sho'," murmured Joe.

NDIGO got the idea these two fellows were sparring with each other; the foreman was measuring Joe and Joe in turn seemed to be reading the foreman. The silence was broken by the youth. "See any tracks north of here?"

'What kind of tracks?" drawled Joe.

"I'd guess you know what kind of tracks I'm meanin'," replied the foreman significantly.

"We're only strangers passin' through," observed Joe in a curiously soft voice.

"Then you wouldn't know what's goin' on in this county," said the foreman. With no more parley he wheeled and rode off. The partners went on until the ranch buildings were lost below the undulating ground. Then, as if both were animated by the same idea, they came to a stop.

"Well, Indigo."

"Well?"

"You know blamed well we can't go an' squeal to the sher'ff," said Joe with a trace of impatience. "We ain't built that way."

"Didn't say we was, did I?"

"An' it'd be the same if we tried to tell those folks at the ranch, wouldn't it? We don' play double."

"You say it," grunted Indigo, not able to fathom his partner's intentions.

"I guess we better sashay back to the beetle-faced gents an' see this through."

"Yeah?" snorted Indigo. "So we should turn rustlers. Then what?"

"Well, if they rustle the critters in the dark and turn 'em over to us, we can throw the stock right back on the Elkhorn range can't we? Nobody's the wiser for the time bein'. Then we pull stakes and get out of this country. By then the real pair o' rustlers from the north will show up an' Annixter's gang will realize they've spilled the beans. They'll shy off from poachin' on Elkhorn again, figgerin' the ranch will be warned. And meanwhile the Elkhorn riders'll see all them tracks on their territory an' keep strict watch. Don't it work out? Nobody's hurt by the transaction an' we won't be squealin'. Leaves our conscience plumb clean."

The distinction was somewhat too fine for Indigo's forthright soul. He said as much, adding, "Supposin' the real pair is on deck when we go back? Or supposin' this gent Elbow Jim has showed up?"

"All we need is today an' tonight. It's a gamble we got to take."

"I dunno why it is you always got to do things the hard way," muttered Indigo. "Always got to embroider an' hemstitch till we're up to our neck in the soup."

"Great Caesar, wasn't you the fellow who wanted trouble a minute ago?" inquired Joe.

"In moderation," was Indigo's reply. "I want a run for my money. This is jus' foolish. Nothin' but calamity can come of it."

"Well, then, we'll keep headin' south an' forget it," decided Joe.

"Oh, hell, didn't I say I was willin'?" snapped Indigo. "Let's go. But jus' remember we're turnin' illegal. Don't forget it none. Mebbe we got good intentions but when we're caught nobody's goin' to know it. I don't see nothin' but sorrow. Well, if we got to do it, then we got to. Come on."

They described a wide circle in the prairie and struck north toward the rendezvous with Annixter and his rustlers. Joe Breedlove was as serene and benevolent as the winds of May; Indigo's pale blue eyes took on a certain narrowed fixity. The both of them were riding into action and each accepted the fact with characteristic expressions.

HEN the partners, thoughtful and somewhat wary, reached the meeting place by the creek, Annixter's gang had not yet returned, and for this breathing spell both Joe and Indigo were thankful. The sun stood at its high mark; being normal men they were hungry, so they boiled a little coffee, fried some bacon and rummaged cold biscuits out of their rolls. After that they smoked in the shade of the cotton-woods, seeming drowsy yet not for an instant relaxing from a constant scrutiny of the horizon. They meant, above all else, to see the rustlers approaching in time enough to count noses. The sun slid west and the, afternoon droned along.

"The beetle-eyed jasper," muttered Indigo, "said we didn't have to do any actual rustlin'. Said we could wait on the county line an' he'd bring the critters to us. Sounds reasonable to me."

"That won't work," argued Joe. "We've got to know where they get said cows else we won't know where to take 'em back."

"Was you aimin' to set each brute in its identical tracks?" questioned Indigo, scornfully. "Joe, I never mistrust yore abilities, but I shore do know you've got an awful habit o' addin' a lot o' unnecessary fancy work to an ordinary chore."

"The closer we stay to those fellows from now to midnight the safer we'll be," returned Joe. "We got a responsibility and we might as well see it through proper."

"Yeah, you're always hell for proper," grumbled Indigo. "Wish I had more cartridges."

"Dust off to the east," announced Joe.

The partners rose up in unison and stationed themselves at no great distance from the waiting horses. The dust cloud grew, and presently riders spurred through it into sight. Indigo squinted long and carefully.

"One more thing," murmured Joe, the words tightening, "in case of trouble and in case it's each fellow for himself, hit for those bluffs toward the northeast there."

"Then," snapped Indigo, rising to his full five feet, five inches, "we'd better hit pronto. They was only five gents last night an' right now they's six. Bet it's that Elbow Jim jasper. What about it?"

Joe looked for himself. Six riders came along at a lope, side by side, rising and falling in unison. The partners swapped somber glances and moved toward their horses. Presently they were a-saddle, yet they tarried.

"No use runnin'," grunted Indigo. "I don't feel crooked enough to let a bunch o' mugs like them chase me."

"Make it two," murmured Joe. He had a small, set smile on his face; and as the party swung into the grove his arm hung free beside his gun. Indigo appeared to have another severe attack of indigestion; his homely, wizened features were twisted at odd angles and the light of battle flickered in his blue eyes, turning them to a queer shade of green. Annixter, foremost, flung up an arm and the group halted. The sixth man, both partners were quick to note, was a shackling gentleman with a fever and ague face. He sat crooked over as if he were saddle-galled, his clothes were wrinkled, and one side of his head was wrapped in a blue neck piece. Undeniably this was Elbow Jim. and Elbow Jim at the present moment looked toward the partners with a vacant, unknowing glance.

NNIXTER slid to the ground, speaking to Joe. "Elbow, the damned fool, wouldn't stay in his bunk. Had to come along. No use tellin' him anything, but he'll croak for it yet."

Joe was the picture of laziness. "Hello there, Elbow."

Elbow Jim seemed to be startled. He focussed his attention, much as a man might strive to see through a fog.

"Who are you?" he growled.

Annixter, shielded by his horse, tapped his head with a finger and winked at Breedlove.

"Shucks," protested Joe, still talking to Elbow, "don't you know yore old friends? Remember the time—"

"Who are you?" demanded Elbow. "What's all this foolishness about? I don't know yuh atall."

Annixter spoke up. "It's the boys you wrote to up north, Elbow. They come down, like you asked. We're all set now."

"No, we ain't set," contradicted Elbow Jim. "Never laid eyes on either party. It's a frame-up."

Elbow spoke with energy; the tone carried conviction. Annixter's head reared and his sparkling black eyes flashed from partner to partner, narrowing and hardening. The rest of the rustlers sat like ramrods in the saddles. Indigo, never a man to endure suspense any length of time, broke in angrily.

"What's the matter with you, anyhow? Ain't you got good sense?"

"What's yore monnickers?" asked Elbow craftily

"My name?" snorted Indigo. And by the way he weaved in the saddle, Joe knew his partner was about to fling down the gage of battle "If anybody around these premises wants to hear my name it'smdash;"

"Hold on," interrupted Joe. He leaned toward Elbow and spoke persuasively. "Now, Elbow, don't you remember the night in the Dollarhide Saloon?"

Joe had seen that saloon in the course of their trip southward. It happened to be in the town that was the seat of the county to the north—that county in which he and Indigo were supposed to do their rustling. And since Elbow Jim was a friend of these two unknown rustlers it stood to reason he must have met them on their own territory and possibly in that very saloon. It was a chance shot in the dark. Elbow obviously struggled with his reason. He had been badly battered on the head and most of his faculties jarred out of him. "Don't you remember that. Elbow?" repeated Joe, in the tone of one talking to a backward child.

Of a sudden Elbow dropped from his horse and walked away. "My God, what's all this? Am I bugs? My haid hurts."

There had been a faint trace of suspicion in Annixter's eyes, but this last moment seemed to dispel it. He came toward the partners, lowering his voice. "No wonder his coco hurts. They's a dent in it big enough to sink an aig. Reckon he's off the track for keeps. Ain't been talkin' straight since he got kicked."

"Looks some thinner to me," observed Joe with an air of considered judgment.

Annixter nodded, thinking of other things. "Well, how about it? See what you want to see this mornin'?"

"I reckon," agreed Joe. "Any time you say."

Annixter's shoulder's rose, his jaws closed like a trap. "Fine! It's three hours to dusk. We travel then."

N THAT gloaming hour when dusk marched out of the horizons and the cobalt shadows piled thicker over the land the party swung to horse and turned due east. They traveled silently and swiftly for a half mile, Annixter in the lead, Elbow Jim alongside. The injured rustler kept mumbling to himself, turning a puzzled eye on the partners. And finally he stopped, bringing the cavalcade to a halt with him. "I'm goin' back," he announced. "What for?" demanded Annixter, showing impatience. "Don't gum up the works, Elbow. We got business on hand an' it ain't like you to lag."

"I'm goin' back," repeated Elbow Jim stubbornly. "Seems like I remember I was to meet some fellows by the crick. It seems like I was."

"Why, you darned fool, here they are, right with us," reasoned Annixter.

But Elbow Jim shook his head. "They ain't the ones. Seems like I was to meet somebody." And without any more argument he left them and rode away. Annixter's head dropped, he stared at the ground for quite a spell. By and by he looked to the partners and in the interval it seemed as if he fought with his suspicions. Indigo's eyes, not visible to the rest of the party in the shadows, turned green again; Joe was relaxed and casual, though his attention never wavered from the leader.

"Maybe," he suggested, "I better go round him up."

"Let him mosey," decided Annixter. "He ain't much help anyhow." His hard glance measured Joe and fell away. "We ride."

They went on into the deepening night, hoofs drumming the ground. A small wind sprang up, the heat of day vanished. Once more the stars were out and the moon hung lifeless on the world's rim. Annixter kept a steady course into the east for an hour, then gradually veered south, checking the gait imperceptibly with the passing minutes. Joe judged that they were at a far corner of the Elkhorn range, traveling away from the ranch buildings all the while. It also seemed to him Annixter was circling toward his objective, not going in a straight line. Annixter, he decided, was a capable hombre and one who easily assumed authority. Certain it was the rest of the rustlers obeyed him without a murmur of dissent; a hard, unscrupulous fellow who would put a good front on anything he did. Joe's experience with lawless gentry was wide and varied; most of them were braggarts and bullies, with a courage that faded in a showdown. He rated Annixter as being of tougher grain. An inner warning bothered him; Annixter's bulky body made a formidable shadow in the darkness.

The leader grunted, and the group came to a halt. Annixter spoke in a rumbling undertone. "All right, Shirtsleeve."

Shirtsleeve Smith proceeded on alone. Annixter touched Joe's arm. "Ain't far now. When we round the brutes we hit direct north into them buttes. They's a pass thataway we go through. County line beyond. It's yore play then. I guess you know the country over there?"

"Yeah."

"How long will it take you boys to polish off the deal?"

Joe answered easily. "Three days."

Annixter seemed to be surprised. "That's pretty sudden."

"We do it sudden," responded Joe. "No use havin' illegal beef around you any longer'n necessary. It's the reason we're still out o' jail."

"Elbow thinks a lot o' you boys," said Annixter. Joe caught a trailing doubt in the words, but he forebore answering. Shirtsleeve Smith's shadow returned.

"All clear."

"We ride," grunted Annixter.

HEY traveled slower this time, the ponies'hoofs making a small and sibilant confusion in the sand. Within fifteen minutes they stopped again. Cattle ahead, cattle-smell in the air and the vague outline of their presence. Annixter spoke. "All right, Shirtsleeve—Red—Mac."

The indicated ones left the group and merged with the velvet pall. The warning in Joe's head grew clearer and more insistent. This Annixter party did things too competently. No fuss, no excitement. It was like a drill. Too smooth, too doggoned smooth. Probably Annixter had a lot of other plans concealed behind that red foliage—for instance, in case he decided there was trickery in the partners' presence. Running those critters back to their original range wasn't going to be half as easy as it seemed.

Cattle moved slowly. Annixter's voice was slightly brittle. "Go ahead, Buck."

The rustler remaining with Annixter rode away, heading toward the Elkhorn ranch buildings. "Allus keep a man on our tail to watch for trouble," murmured Annixter.

Joe feigned a hearty approval. "I shore like yore style, Annixter. Wish you was with us boys up north."

"It's an idea," grunted Annixter. The man was human enough to be flattered. "This country's gettin' washed out. They's a sher'ff who's hell on wheels. Elbow won't never be good no more. An' we're gettin' too prominent in the county. Said sher'ff was elected on a promise to clean us out an' the fool actually figgers to do it. Well, here we are."

Cattle moved by them at a shambling, uneasy pace. Soft oaths broke the night, and the slap of quirts. Annixter and the partners fell in behind. Joe assumed a sudden authority. "Lay on 'em now. We've got to mosey."

Annixter mildly protested. "What's the rush? This is easy."

"My style," replied Joe a little more crisply. "Didn't I say we worked fast?"

The pace increased; Annixter sidled off and was gone for some time, during which interval Indigo edged closer to his partner and started to speak. Joe interrupted with a quick phrase. "Neat work, ain't it Indigo? I like these boys' style." And Indigo, warned, held his tongue. A rider drew up to them, coming from some unexpected angle, and rode between, never saying a word. Annixter returned, also silent. The mass of shadow that was the rustled stock weaved uncertainly. Hoofs and horns clacked; the pound and shuffle of their gallop rose into the night.

"Shirtsleeve—drop back," snapped Annixter And the man riding between the partners faded and was lost. "We're leavin' a broad trail. But they was an Elkhorn rider makin' the circle this mornin' an' I doubt if he'll get around till late tomorrow. That's ample time for you boys?"

"Plenty," said Joe.

"We'll meet yuh four days from now at the crick," suggested Annixter. But Joe knew that was more of a request than a suggestion. Annixter seemed to grow more gruff as the night wore along; more distant.

"Agreed," was Joe's response.

FTER an hour the ground began to grow rougher and the outline of the broken country stood up before them. Annixter disappeared again. When he returned Joe felt the stock turning to another point of the compass. They dipped down and up several arroyos, they passed a clump of jackpines. On they hurried. The slope grew steeper, it turned rocky underfoot, the pace slackened and the horses began to breathe harder.

"The pass," said Annixter and for the third time rode off. The cattle were at a walk. High ground stretched on either side and the walls of a small canyon narrowed on them, pinching the whole procession to a long, trickling line. There were trees up this way, the breeze scoured against them, fresh and cold. Riders lagged and fell in behind. Then they were gong up a stiff grade—a grade that of a sudden dropped into a summit meadow. The trees marched out to them, surrounded them; a coyote barked, the party came to a halt.

"Your turn, I reckon," said Annixter, returning. "Down the far slope is the county line."

Joe took off his Stetson and dropped his watch into it. Then he lit a match and discovered it was even twelve. All this had taken longer than it seemed; dawn wasn't more than four hours removed—four hours in which to undo all that had been done. "All right," said he.

"Don't let this rough country fool yuh," warned Annixter. "Bear due north. Either way from that'll push yuh into a lot o' blind pockets. I'd go on straight to the line, but it's better we go back an' make a lot o' tracks leadin' another direction. One o' the gang, howsumever, will keep a lookout around these parts after daylight. If he sees anybody comin' afore yuh get far enough off he'll send up a smoke signal. Watch yore back trail for that."

"Good enough," murmured Joe. The rustlers had collected, waiting for Annixter to finish. The man tarried, saying nothing at all, yet bending close to Joe. Joe saw only a blur of Annixter's face; then the leader withdrew.

"Four days from tonight, at the creek," he called.

"That's right," agreed Joe. "Adios."

The rustlers dipped down the grade and presently the partners, listening carefully, lost the sound of them. Indigo sighed, as if he were pulling himself up by the roots. "Well, we got somethin' on our—"

Joe's arm touched him. "Easy, Indigo. Hold it a minute."

They waited five minutes longer, but nothing stirred the profound stillness of this night save the slight and uneasy movement of the stock. Joe stirred and spoke in a matter of fact voice, slightly louder that appeared necessary. "All right, now we've got to drive 'em hard as long as it's dark. Let's push 'em."

They pressed against the rear of the cattle. Indigo rode around to edge in the flanks Once more the momentum of the mass carried the small herd along the trail and across the level ground of the diminutive meadow. Under cover of this orderly confusion Joe closed upon Indigo and spoke just above a whisper. "Keep 'em going five-ten minutes, Indigo. I'm waitin' on the trail. Think somebody's apt to be followin' us."

E LEFT his horse at the side of the trail, back in the pines, and retraced his way afoot for a hundred yards. Here he stopped and waited. The noise of the cattle came to him as a muffled echo. Elsewhere was no movement save the slight scouring of the wind in the pine tops.

"Somethin' bothered that Annixter gent," he said to himself. "He's a shrewd duck. Think maybe he'd have a man track us till we got out o' the county, jus' to find if we was up to specifications."

He drew back a yard or so. A horse came up the slope, picking its way cautiously and with only the slight shuffle of its hoofs and the small abrasion of saddle leather to announce it. Well, there wasn't need for much caution; the noise of the herd would drown out this kind of pursuit. That fellow Annixter was nobody's fool, he took care of all bets. Joe's arm dropped toward his gun and he retreated still farther. The rider was muttering sibilantly to his animal. "Get along—get along. Don't yuh know cow-smell?" Man and beast were abreast of Joe. Joe tarried one more instant; then his tall body weaved across the space and came up somewhat behind the rider. His arms swept forward and all his strength snapped into them. The horse reared. Down out of the saddle came the rider, fighting. A bellow woke the echoes as he hit the ground. Joe struck him on the face with a driving blow and his gun touched the man's ribs. "Easy, brother. Make it easy." There was a quick turning and slashing of legs and arms, a subdued volley of oaths. Joe's gun barrel laid along the fellow's head and then resistance died. The herd, evidently, had stopped, for Joe couldn't make out their progress; but Indigo was coming back at the gallop.

"All right. Draw in, Indigo. I got a nibble. Bring me yore rope."

Indigo groped toward Joe. "He's out? Lessee his complexion, Joe. An' do yuh reckon the rest o' that gang heard the yelp he lets loose."

"Don't believe so. They left him behind to scout. I figger they're well on the way to the crick by now. Light a match."

Yellow light sputtered under the protection of Indigo's extended hat-brim and the flickering rays fell upon the horse-jawed Shirtsleeve Smith. Shirtsleeve was unconscious and unlovely. The light sputtered out; Indigo wasted no time with his lariat, nor did he waste gentleness as he looped and knotted the cord about the recumbent rustler. Joe started to untie the man's bandanna and fashion a gag but Indigo, catching on to the operation, interrupted. "Lem-me do that. You can palaver a whole lot better'n me, but when it comes to such chores as these here I'm the golden-haired lad. If yuh want to know the positive truth, Joe, that feller Annixter reminds me o' bad medicine."

"Make it two."

The partners boosted the still mentally absent Shirtsleeve Smith to his feet and carried him back through the pines to a spot that felt secluded from the open ground. Then.they retraced their way toward the herd. "Good thing them brutes is tired or they'd be scattered from hell to supper. Joe, I ain't no saint, but it gripes me to be an amachoor rustler. Tain't a matter of morals either. It's a matter o' legal impediments. To state the bald facts it's a matter o' a knot under one ear."

"We've got less than four hours, Indigo. Have to hustle this."

"Why not run 'em anywhere down into the flat country an' leave 'em. That's near enough ain't it?"

"Not by five miles it ain't, Indigo. Supposin' Annixter should be ridin' this way at daylight an' see 'em all ready to be pushed back up here out of sight. He'd do just that. And there'd be our good intentions shore shot to pieces."

Indigo grunted. "You're just doin' fancy work now an' you know it. Yuh just got an idea an' yuh won't let go."

"Put it like that," agreed Joe. "Let's mosey."

HEY circled the cows and milled them back upon the trail, traveling across the meadow and down the slope. Presently they were on level ground again, urging the brutes to a gallop. They had no exact idea as to where the main part of the Elkhorn herd ranged, but being old and experienced at night riding they did know the approximate direction and the approximate distance back along the route. About an hour and a half of this progress would bring them to a good enough destination. Another hour and a half would put them well out of the way—just as dawn arrived. Not exactly a comfortable margin, but still sufficient if they kept fogging on during the day.

Joe looked up to the dim stars and grinned wryly. Well, maybe Indigo was right. It was a stubborn idea, this of running the brutes back to where they originally had been. It needn't be so close, almost anywheres along here was really good enough. But Joe Breedlove, as mild and peaceable man as he was, had queer streaks of illogical sentiment in him. He loved, above all else, to put an adequate, and artistic end to his chores. Indigo, now, was more of a realist. When the small and wizened one got into a jackpot his method was to drive ahead and tap somebody on the coco. That was effective, but to Joe it wasn't satisfactory. Joe's method was to use his silver tongue; if that failed then he resorted to stratagem, tied his man and lectured the unfortunate on philosophy.

In the present case there happened to be another motive. Up among those stars was the face of a girl—the clear and rounding face of Julie Stovall with her auburn hair and her gray eyes. She had looked at him with favor, there had been something of understanding in the short, grave glance. It reminded Joe of earlier days, of a time when he was a stripling and his future seemed to be settled among quiet ways. Well, that had gone under the bridge. But though time softened and mellowed the disappointment, it only took such a woman's look to unlock Joe's treasure box of memories. And then Joe's smile became a little wry and the magnificent chivalry of the man flamed high. As tonight.

Out of the darkness came a tremor of sound that was above and beyond the rumble of hoofs. Indigo had heard it too for he came in from a flank muttering.

"Hear that, Joe?"

Joe bent his head and listened. It vanished, then it came again, more strongly. Tndigo grumbled. "To the right of us. Listen, we're makin' enough noise to wake the dead."

"Let the brutes run on a ways," murmured Joe. "We'll stick here."

"I'd jus' as soon orphan them cows right now."

"Easy, Indigo. Sift to the left some. You'd think the whole county was out ridin' tonight." His voice trailed to a mere whisper. "Sift. They ain't far away."

The cattle galloped on a piece then, no longer pressed, broke the pace and split in twenty different directions. Joe Breedlove saw the compact shadow of them dissolve and disappear. They were all over the compass. He heard Indigo shift restlessly in the saddle. Elsewhere was the sound of somebody crcling and advancing. Elkhorn outfit—posse—rustlers? Joe didn't know, but any of the three possibilities spelled poison for him and Indigo. It was hell to be honest tonight, and it was hell to be crooked. However, the straying cows shielded them somewhat.

"Never get "em together again," he thought to himself. "Looks as if we leave 'em here and fog."

HE outline of horse and rider moved in. Behind was the clink of a bridle chain. There was more than one and they were quietly prospecting the area, quietly dragging back and forth. Joe felt a presence to his left hand and he drew himself up, his head sweeping from side to side. Best to freeze until these gents got tired and passed by. If it happened to be Annixter's party a little lead-slinging wouldn't hurt, but if it were either Elkhorn men or a posse the less gun play the better.

Indigo couldn't keep from stirring. Joe put out his arm to touch him in warning. At that moment Indigo's horse, smelling his own kind, elected to whinny. Suddenly riders drove toward the partners from all angles and there was a slapping and a jingling of gear and a challenging of voices.

"That's them! Bear down!"

Annixter's men!

"Out of this," muttered Joe, turning his horse. "Back to the buttes. Come on, Indigo, don't get reckless."

But Indigo had labored and sweated hard enough for his fun and now he meant to satisfy his ingrained instinct for trouble. Joe saw the little man rear in the stirrups; Indigo's cracked, falsetto tones sheered the nght in ribald defiance. "Yuh suckers, come an' collect!"

Annixter's voice, hard and crisp seemed to carry over their heads. "Draw off, Mac." And at that somebody at their rear spurred away. Then the tornado struck. Mushrooming points of light glowed, flat waves of sound spat in their faces. They were whip-sawed. Indigo's gun roared, the wizened one swayed in his saddle like a common drunk and he yelled again. "What smells around here? Polecats!" Joe, who fought more methodically sent a brace of bullets toward a gun-flash on his flank. Annixter shouldn't have more than four men, for Shirtsleeve Smith was tied and cached up in the pines. But in spite of that the rustler leader had found help somewhere; he could tell it from the revolver echoes. Must be six in the bunch. And they were whirling around like raiding Indians. Joe made up his mind on the spot.

"Come on, Indigo. Shells cost money an' dead is a long time."

They reined about and raced away. For a moment the volleying diminished; then they heard Annixter's gang in full pursuit. The protection of the buttes was about a half hour off, or less and the shadows were blacker—that piling up of shadows that came just before first dawn. The sharp wind struck their cheeks, the stars were dim. On they plunged.

It seemed to Joe that they gained distance. All firing ceased for a little while and there was only the pound of their own animals beneath them. But, some minutes later, Joe's ears caught the echo of the trailing rustlers again and for the next quarter hour the partners laid on their quirts with the knowledge they were but a scant hundred yards ahead of catastrophe. Presently they reached the rougher ground and Joe veered a little.

"Hear 'em, Indigo?"

"Nope."

"Neither do I. They ain't direct behind any more. Damn that Annixter gent. He's as slick as a boiled onion."

"Their hosses is about as tired as ours, Joe. An' they can't be exactly shore which direction we take."

"That ain't the answer," grunted Joe. "They got somethin' up their elbows."

"Well, there's the end o' a good deed which never got done," muttered Indigo. "I wasn't so cracked about this business o' foggin' them critters clear back. But now that them dudes have spoiled our little journey I'm all in favor o' seein' it clear through."

"We ain't finished yet," Joe replied. "We'll hole up in the timber an' think about it."

They struck the entrance to the pass, wound in and around the rugged slopes and arrived at the narrowing walls once more.

At that point disaster overtook them. Hemmed on either flank they were arrested by Aninxter's harsh and peremptory order rolling down from the fore. "You're boxed. Stop right there!"

"Not me!" cried Indigo and sank his spurs. The partners flung themselves onward. The defile rang like a forge, bullets whipped at them from front and rear. Joe felt the shock of Indigo's horse colliding against his own pony and the succeeding moment Indigo was calling up from the ground. "They plugged my brute, Joe. Go on. beat it!"

Annixter sang at them again. "Throw yore guns thisaway!"

Joe slid from the saddle and retreated to his partner. The rustlers pressed nearer from either direction, barely outlined in the dim morning's dusk. Well, they could make a fight of it yet, but what was the use of the extra killing? Annixter had only to draw back, post guards, and wait for daylight. Meanwhile here he and Indigo were, exposed to the crossfire. This was the end of one episode; tomorrow was another day.

"All right," he muttered, "we're through."

Indigo swore like a man in pain, but Joe touched his partner's arm, whispering. "Remember what we decided once, old-timer."

"Stop that parleyin'!" boomed Annixter. "Throw yore guns thisaway or we'll open up!"

The partners obeyed. Annixter's men crept along cautiously and in a moment Joe and Indigo were prisoners. Light wavered across the eastern horizon.

MMEDIATELY after the partners were disarmed and both tied into Joe's saddle, Annixter left a single man to guard them and withdrew down the slope a few yards to hold a parley. There seemed to be a division of opinion in the party, a heated contest between caution and recklessness in which the leader lost ground. At first nothing but the general sound of their talk reached Joe and Indigo, but as the discussion grew warmer they caught what went on.

"Daylight's about here," said Annixter. "They'll be an Elkhorn man ridin' circle. Why not wait till dark?"

"By which time said gent will see all them tracks an' then the whole danged ranch will be on the scout. If we git 'em, we got to git 'em now."

"They'll shore trail us then," argued Annixter.

"What of it ? Ain't these hills big enough to cache in till dark? Then we can slip the stuff on acrost the line."

"It's a big risk," grumbled Annixter. "Don't you boys reco'nize the fact we got to live in this section? You're out of it—we ain't."

"Risk either way. We come a hell of a long distance on Elbow's call an' we can't stew aroun' here for a week while the excitement simmers down. If we wait another day to git them brutes we're only lettin' them folks fix a nice trap. If we go round 'em up now we can chose our own country to fight in—if we got to fight."

"I don't like it," protested Annixter. After this followed a flurry of argument. Joe understood then the situation. The pair of real rustlers from the north had arrived and Annixter's party had fallen in with them. A silence came over the group, broken finally by the leader's reluctant assent "All right. We'll go do it. But I got to leave a man out there today to take care of the Elkhorn line rider. Can't have him discover tracks an' run for help before we git everything settled an' out o' the way."

"We'll hide the critters up in the timber ontil dark," said one of the northerners. "Then we fog back with 'em. Shucks, what you afraid of?"

"Talk's cheap and it don't buy no ribbons" muttered Annixter. He returned to the partners. "What'd you highbinders do with Shirtsleeve?"

"Up in the brush takin' a wink," drawled Joe.

Annixter accepted this with an ominous mildness. "It's the fool's own fault for not bein' more careful. Well, I give it to you boys for bein' slick. We'll count up the marbles later. Elbow, come here."

The figure of Elbow Jim appeared through the filmy shadows. "Yeah?"

"You tail these fellows back into where that big cedar is. An' don't have no lapse o' memory either."

"Don't worry," mumbled Elbow. "I ain't all finished."

Annixter retreated, the whole party rode down the trail. Elbow grunted at his prisoners "Mosey up. I may be crazy, but I know a face when I see it. Go 'long."

HE horse carrying both partners moved up the trail and back to the small meadow. It was light enough now to distinguish the beaten pathway and the occasional stumps and boulders.

"Turn left," said Elbow, and circled the partners' horse to swing it off the trail into a lesser and much overgrown trace. This led them through ever-thickening underbrush, down steep slopes and along miniature canyons. From the prairie this mass of buttes had not seemed large, but now that they were away from the open country everything took on greater proportions. It was a good place to hide in or be lost in. Apparently the pass cut across the most gentle part of the ridge, for the longer they traveled the more they climbed and twisted; once they had sight of a waterfall spraying against sheet-rock a hundred feet below. Then they were more thoroughly enmeshed in the pines and the clinging brush.

"Turn left," droned Elbow, and again rode in to press the partners' pony. They broke through what seemed a wall of trees and came out in a glade not more than fifteen feet across. Elbow stopped and got down. Daylight flooded down, dew sparkled on the grass.

"This," said Joe in genuine appreciation, "is shore pretty ain't it?"

"Nice place for a murder," was Indigo's gloomy response. "Say, fella, you goin' to keep us up on this barbecue platform much longer?"

Elbow circled the pair, looking out from under his shaggy brows with a sly shrewdness. "No tricks, no tricks on pore ol' Elbow. I may be cracked but it don't hurt my shootin' none."

"Tricks with what?" snorted Indigo. "I can't do nothin' but google my eyes."

Elbow came over and cut the ropes fastening the partners to the saddle. "Git down —march over an' sit agin that log. No—not so clos't together. Yuh might fiddle with t'other's wrist hobbles. Ol' Elbow's still got a lick of sense."

The partners with their hands tightly lashed behind them, sat against the designated log and held their peace. Elbow roamed the small glade impatiently, his head turning to odd angles and every now and then he murmured a garbled phrase to himself. Anything interested him, many objects puzzled him. Once he stooped to the ground and was thus hunched over for a matter of minutes. Then he came toward the partners and swept them with the same sly look they had observed before. The longer he watched the more uneasy he grew, until at last he spoke.

"I don't know you gents."

"Why of course you do," said Joe soothingly. "We've hoisted many a glass at the Dollarhide."

Elbow Jim wrinkled his nose and peered down it somberly. "Ol' Elbow's shore cracked. Once, by Gabriel, there wasn't a man in the county what was able to down me. This was my gang, yuh hear me? Bo Annixter's boss now. Oh, Bo's all right, but he couldn't hold a candle to me. Them dam' hosses.

"Remember the Dollarhide?" persisted Joe.

"I know what I know," mumbled Elbow Jim, and he looked very shrewd.

Joe studied the log casually. "I'm sorter uncomfortable here, Elbow. It's a poor way to treat an old friend like me. But of course you got orders from Annixter an' I reckon you got to obey 'em "

"Once I didn't," was Elbow Jim's quick reply. "But I'm out of it now. Yuh don't know Annixter like me. When he's got the bulge he keeps it. I'm kinder sorry for you gents. How'd you git in this scrape?"

He seemed to have lucid moments, moments in which he understood what had taken place. Then quite of a sudden his mind went off the track and he was both puzzled and sly, forgetting what he had said the instant previously. Joe went on. "I'm sittin' on a rock. Got any objections if I move over a little."

"Jus' so's yuh don't git nearer the skinny feller," agreed Elbow Jim.

OE moved himself in a series of crow-hopping jumps, back—all the while touching the log.

Indigo's semi-closed eyes flickered with a baleful green light and he utilized Elbow's averted attention to do something with his pinioned hands. Joe's progress put the partners farther apart and made it more difficult for Elbow to keep them within the range of a single glance; nor did Elbow notice that when Joe stopped and leaned on the log he had his back directly against an out-thrust knot with a splintered edge. Joe timed this well. Elbow moved around the glade with a sorry jaded expression on his battered face. The man was in bad shape; fresh blood caked the bandanna on his head.

Joe's body went rigid with effort and his arms snapped powerfully and fell limp as Elbow faced the partners again. "Yuh dunno Annixter. What he's got he keeps. Who're you boys? I'm cracked all right, but I know what I know."

After that he resumed his moody tramping, head swinging with his feet, gun dangling loosely in his fist. The morning wore along, the sun marched upward in the sky, the glade was flooded with a bright hot light. The partners seemed to accept their situation, attempting no more talk; but in those odd intervals when Elbow's attention left them Joe's arms bent outward, twisted and flexed. Beads of sweat crusted his forehead, stolidness touched his eyes—a sure sign that Joe was torturing himself

It was more than an hour—nearer two hours since they had been captured—when they heard a voice sounding far through the trees. Elbow turned his back to the partners and cocked his head. Indigo stirred and looked warningly to Joe; the latter nodded grimly.

"Elbow," he purred, "be a good gent an' roll me a cigareet. Seems like you'd ought to treat an old friend like me better'n this."

Elbow holstered his gun. "I been in the Dollarhide all right." He holstered his gun and went searching for tobacco and papers. Brush rustled nearer, somebody swore Elbow rolled the cigarette with a tantalizing slowness, so slowly that Indigo began to squirm restlessly and Joe struggled to keep a serene countenance. Elbow shambled across the space, the cigarette between outstretched thumb and forefinger. "No monkey business," he warned Joe. "I ain't to be took in nobody's camp. Open yore mouth."

He was within a yard of Joe. The latter tilted his shoulders forward, he had his feet crossed beneath him. As Elbow took the next step Indigo suddenly called out, "Say, Elbow, what's this over here "

The trick was about to work. Elbow swung. Yet the spring Joe was on the point of making, never materialized; the impulse, swiftly checked, almost carried him over on his face and thus he sat as Shirtsleeve Smith smashed into the glade, raging like a madman.

"Elbow, yuh passed within a foot o' me— an' there was I, stuffed like a turkey! Couldn't talk, couldn't move! I aim to bust somebody's ribs. There yuh be, daggone yore hides! Whicher one manhandled me?—whicher one o' yuh gents stuffed all that grass in my gullet? I got a notion to fill yuh full o' pine needles."

"Good mornin', Shirtsleeve," drawled Joe. "Hope you slep' well. How far was you aimin' to trail us last night?"

Shirtsleeve advanced, the horse-jawed countenance crimped in lines of malevolence. "How'd you know I was trailin'?"

"Always been able to smell a skunk," was Joe's deliberate answer.

"Here's where I drum a tune on yore ribs!" snorted Shirtsleeve, and stood directly over Joe.

NDIGO made a noise that was indescribably contemptuous. It

pricked Shirtsleeve Smith's vanity as a pin might explode a balloon.

He swung toward the small partner, ready to blast him with profanity. Elbow Jim gurgled, but it was then loo late. Joe's arms and hands shot out in front of him and his body sunfished through the air, striking Shirtsleeve as a battering ram. Shirtsleeve's angular framework was too loosely coupled to absorb the impact; every joint in the man snapped, his head flew back and he bent double. Joe's fists struck Shirtsleeve's lantern face twice and the man pitched over. Elbow Jim's gun wavered uncertainly, trying to catch a clear target of Joe. Once more Indigo, who hadn't yet moved, served a useful purpose by yelling at Elbow and thus diverting the injured rustler's attention. It was, however, hardly needed. Joe—the man of leisure, the slow-talking, serene appearing man of the world —exploded like a box of dynamite. Shirtsleeve never had a chance. He was down before he understood what happened; he struggled a little and was battered again. Joe heaved him up and made a shield of him; Joe whipped the gun from the prostrate one's holster and drew a bead on Elbow.

"Drop that piece, Elbow!"

"I got orders "

"Drop it you crazy loon or yore dead as yesterday!"

The summons cracked over Elbow's head, making him flinch. There he stood, a sorry and troubled figure, fighting off the deadly mists in his brain. He knew he was licked, he knew that for him the days of usefulness were over and that never again would he stand as an equal among other men. Henceforth he would be a chore boy, a half-caste creature to be pitied or laughed at or kicked about; always he would be plagued by that curtain which darkened the brightest day and cut him off from his own past, rising only for an instant—an instant in which, as now, he saw the horror of his case and the utter futility of living.

In this flickering instant of self-knowledge Elbow Jim looked on down the alley of time and found nothing there for him. There was a grain to Elbow, there was pride. Why should he, who had commanded men now sink to the level of a camp dog ? One thing he could do. He could carve his own epitaph and let men know that he was master of himself to the very end. So he turned and for a small space looked into the muzzle of Joe Breedlove's gun.

"Drop it," repeated Joe.

Elbow shrugged his shoulders and passed a glance to the still roped Indigo. He could kill Indigo, but if he did the other partner's leveled gun would crash into him before he turned his own weapon inward. And Elbow didn't wish it to be that way. Very slowly the gun in his fist veered and rose. He heard Joe Breedlove's last brittle injunction. And that was the final word that reached him from any mortal. He sent a bullet into his own tortured brain and fell.

"Well, by—" shouted Indigo, startled out of his calm.

Joe's revolver fell and a clucking noise passed his lips. Joe loved his fellow creatures and the sight of this moved him tremendously. "The pore devil—the pore old fella. Well, that's best." He flung up his head, hearing fresh sounds beyond the glade. The main body of rustlers were returning; that shot had warned them and it was only a matter of minutes. "Hustle over here. Indigo!"

Indigo rose and galloped toward his partner. Joe unraveled the knot holding indigo's wrists and transferred the rope to Shirtsleeve's arms. The fellow was not entirely out but there wasn't any resistance in him. Once more he was a stuffed turkey. Indigo ran over, got the dead Elbow's gun and belt, and collected the horses.

"Them boys will think we killed Elbow," said Indigo, "which impression I hate to have 'em get. This Shirtsleeve guy ain't out of the hop enough to understand."

"Let it ride. Damn the luck, we could've had the drop on that party if they hadn't heard said shot. Now they'll watch for trouble. We've got to sift."

HEY swung up on horses and started through the narrow exit—the same route by which they had come. The rustlers were not in sight but the sound they made indicated an uncomfortable nearness.

"It won't do," muttered Joe. "We've got to make our own trail. Come on."

They turned, recrossed the glade and forced a way through the brush. It was slow, nervous work; within a few minutes Annixter's booming echoes announced the discovery of what had happened. Hard on this came the leader's harsh order. "Spread an' foller. They don't get away, hear it? Knock 'em out o' the saddles! Bring down the hosses. Shouldn't of left Elbow in charge, but I didn't—Shirtsleeve, yuh yella mongrel I got a notion to ride my hoss over yuh! Come on!"

"The boy's full of business," said Joe. "Well, he can't buck this brush any faster'n we do."

"No, but he sounds powerful mean," grumbled Indigo, "and he knows this country a heap better'n us. I'm for makin' a stand on the premises."

They put the worst of the brush behind and arrived at a deer trace dodging along the uneven earth. Joe went before and jockeyed his horse into a respectable run. Overhanging boughs whipped them severely. "How about bitin' back?" persisted Indigo.

The rustlers were in full pursuit; it sounded like a stampede. "What for?" queried Joe. "All we can do is argue an' run some more. I'm awful tired of this deal. My idea is to shuffle the cards again. If we stick here we're liable to be boxed an' licked. Then when it gets dark they'll sashay the stock on over the hump—and what've we got to show for all this sulphur an' brimstone, presumin' such to happen?"

The trace dwindled to nothing, leaving them high and dry in the brush. Once again they bucked through it. The rustlers, taking advantage of the same deer trace, closed the interval. Annixter's violent shout trembled on their ears. "Mac, strike toward the draw! They're headin' for it!"

Indigo grunted. "That's advertisin' for us to stay away from said draw. Well, doggonit, this was yore bright idee in the first place. So get another idee quick or we stop an' argue. I hate to run—it blights my morals scandalous!"

The brush gave way to a more or less open stand of pines; across this they swept. Beyond was a burn with charred snags trooping side by side. On they went, the rustlers seeming to slacken the pace. "Well," decided Joe, "I hate to think of 'em gettin' away with Elkhorn's cows, knowin' what we know. Guess we better swallow some pride an' ride for help."

"Which was my recommend in the beginnin'," jeered Indigo. "It's a hell of a time to be thinkin' of it now. How d'yuh suppose we get outa this wilderness without bein' sniped at?"

The ground began to wrinkle and grow rugged. Ahead they had a vista of lava rock bereft of any kind of foliage. Acres of it, where black pinnacles reared and fell into deep pits. And beyond that at some undetermined distance the ridges dropped into the prairie. The partners had seen the bluffs descending sharply to level ground while riding across country the day before and thus they knew what lay ahead. Heat-haze rested on the horizon; three hundred yards farther brought them to a draw sloping down into the prairie. Joe drew rein. He had made up his mind.

"Somebody's got to go down thataway and hit for the Elkhorn. Somebody's got to stay behind and entertain these gents a few minutes."

"That," declared Indigo with alacrity, "is my job." The wizened face flared with the only emotion it was capable of expressing, a grim and embattled pleasure; those washed blue eyes flickered, changing to an emerald green. "You travel. I'll stop 'em long enough to let yuh get a good start. Then I'll work back into the rocks an' pick my teeth."

"Pick lead from yore ears, you mean," muttered Joe. "They'll try to rub you out." His hand ripped at the buckle of his gun-belt; he flung the belt and revolver across Indigo's saddle. "You need this too."

"How about you?" protested Indigo.

"I'm runnin', not fightin'," was Joe's answer.

OR an instant the partners studied each other. It was one of the few times in their joint career they had separated during trouble and it left both uneasy. Together they made a formidable, efficient machine. Asunder they were lost, like man and wife divorced. Yet there was nothing either could say at such a juncture for they were not made to say pretty sentiments. So Joe shrugged his shoulders and turned into the draw. "Be good, kid. I'll hustle back."

"Uhuh," grunted Indigo, watching his partner go. "Don't rush. I'll say I earned this fun an' they ain't no use cuttin' it short."

Joe dipped around a point of brush and was lost save for the clatter made by his pony's hoofs. And that scarce had died when Indigo flung himself into the draw and crawled up the far side. Here was a fine breastwork of rock. Back of him were other equally-good shelters in case he had to retreat. He jumped from the saddle, shying his horse into an adjacent pit, and settled to his haunches.

Annixter's men raised a great noise as they came. The chase had grown so hot that it made them careless for they plunged out of the concealing undergrowth and through the straggling pines with no side survey, no flanking forays. Annixter's eyes were pinned to the fugitive tracks; up to the edge of the draw they swept and halted. Annixter stood in his stirrups, looking down the draw; his arm made a semi-circular gesture and the rest of the riders closed toward him. There were six of them besides Annixter, and Indigo, raising his gun, admitted he had at last matched himself against superior odds. For Indigo that was a tremendous concession.

"One set of tracks goes down there," said Shirtsleeve Smith, indicating the draw. "Other gent has hit for the lava rock."

"Prob'ly jus' to throw us off," snapped Annixter. "They're both foggin' for open country, you bet. Back to Elkhorn, the dam' spies. Come on. If they reach help we might as well quit business."

"Don't be in no rush," sang out Indigo and placed a bullet just short of Annixter's horse. The distance made accurate revolver work out of the question, but all Indigo cared about right at present was to announce himself and keep the party occupied. The compact formation around Annixter was scattered instantly, as if a bomb had fallen in the center. Dust rose, men streamed back, spreading out. Annixter's voice rose again, though not loud enough for the intrenched Indigo to make out just what the man was saying. It didn't matter, however, for the small one's glittering green eyes saw them charge through the trees and momentarily disappear in the direction of the draw's head. That was clear enough; they meant to flank and surround him.

Indigo muttered wrathfully, "why don't they fight in the open?" and took steps to remove himself from the immediate area. The horse was no good to him out here where a yard of level ground ended in a forty yard crater or an immense monolith. Regretfully he left the pony and struck straight on toward the end of the ridge. "When a man's got to take to his own locomotion," he soliloquized, "the situation ain't bright. Anyhow, Joe's clear an' safe."

NDIGO stood behind a rock shelf and watched a row of sombreros bob toward him, over on his left hand, a hundred yards away. The outlaws had deserted their horses likewise, which for a brief spell gave him the audacious idea of slipping across the draw and stealing the animals. He counted the hats and immediately decided not to be foolish; there were only five in pursuit. Evidently Annixter held a man in reserve—perhaps sent him on Joe's trail. Anyhow, it wasn't wise to buck into uncertainty. So he retreated again, keeping well out of sight. Once a burst of shots broke the silence and the lead slugs spattered an adjacent lava formation. Indigo derisively wrinkled his nose and made an insulting noise. They didn't know exactly where he was, therefore they prospected. But Indigo had cut his wisdom teeth in trouble and he wasn't to be tricked like that.

He crawled up and he slid down; he rolled over, he rested and he traveled again. The sun bit into the back of his neck and the lava rock was as sharp as broken glass. He began to sweat and at that point he realized he was going to be intolerably thirsty before this day's work was ended. Right there Indigo's wrath exploded sulphurically and all the rustlers' ancestors suffered blighting comparisons. Indigo was a man who could endure all sorts of hardship and privation willingly and cheerfully, provided he did it of his own accord. But the fact was, right now, he was being driven by a collection of mangy, louse-infested, mutton-eaters and it hurt his pride to think they were the cause of all this misery. He very nearly rose up from his concealment and challenged them. Some divine angel saved Indigo from his own impulse that time, or perhaps long association with Joe Breedlove had instilled a little caution in him. He kept on. And the farther he went the narrower the ridge became. Nothing was to be seen of the rustlers. Ominous quiet held the flickering heat haze. Twenty yards brought him to the end of his trail. He climbed the side of another huge bowl, hooked his chin over the rim and found himself staring down a matter of four hundred feet to the prairie floor. It wasn't a sheer drop, but it was abrupt enough to bar Indigo from going farther. "A centipede would shore bust his laigs goin' down that," he grunted. "Here's where we fort up."