RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

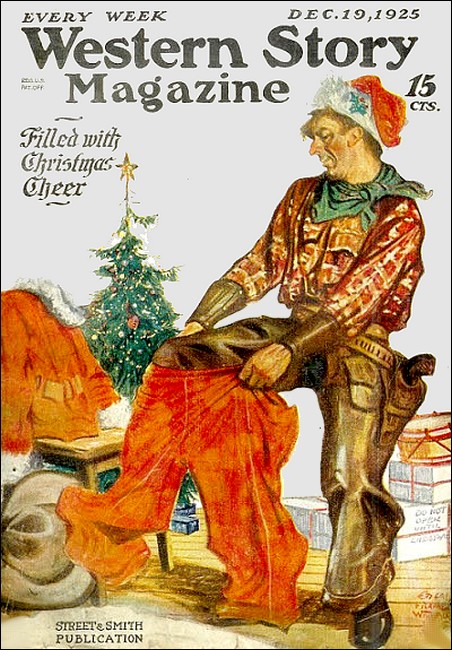

Western Story Magazine, 19 December 1925, with "Prairie Yule"

IT was Christmas once more. Old man Budd stared out at the snow-crusted jack pines and tried to find the Bend- Klamath Road. It was completely covered by the driving storm. It was good to be inside the store, hovering over the iron-jacket stove which showed red hot around the edges. A man had no business to be abroad in the pine flats and prairie of Central Oregon today. Budd toasted his huge body by the fire and tried to be thankful, yet he could not seem to get himself into the festive spirit. The holiday mood eluded him. It was pretty lonesome away out in this half way house to creation, he thought. As far as it being Christmas, well, he didn't find it different from any other day. The warped old boards of the store didn't keep out the wind any better. There wasn't any better draft in the chimney. The rats didn't seem to make any less noise in his garret.

"Spendin' Christmas alone," he muttered aloud. "Ain't it a sweet note for an old codger like me to be here without a soul to talk with? Dave Budd, it's the last Christmas you get stuck like this."

He stopped his soliloquy and made for the door. He had heard the distressful clatter of the mail stage's horn. When he got to the porch, he saw young Slim Bullit abandon the stage in the middle of the road and waddle toward shelter. Budd pulled him up to the porch and into the house. "Slim, ain't you got no better sense than to drive on a day like this?"

The young fellow slid out of his mittens. "Say, it's cold! Budd, gimme a package of cigarettes. Got a cuppa coffee handy? You darn tootin', I'm making the drive today! Say, that bus is plumb loaded to the guards with Christmas presents, and I gotta get 'em through."

"Christmas," snorted Budd. "Reminds me how old I'm get-tin'." He poured out a cup of inky-looking coffee and passed it to the young driver. "Was a time when I liked to be alone. 'Tain't the same now. Need company."

The driver downed the cup of coffee and became convulsive. "Gosh, what you put in that stuff, lye or blue vitriol? Shore is gonna keep me warm. Well, gotta hit the skids now. Long ways to Klamath."

"Durn fool," said Budd. "Stay here until the storm stops. It's plumb dangerous this a-way."

"Nope. U.S. mail has gotta go." He dived out into the whirling snow and ran for his motorized mail stage. He cranked it up and jumped inside. Budd saw the wheels skid, buck the rapidly forming drift, and the mail stage go down the road, swaying drunkenly from side to side. In a moment he was out of sight.

It made Budd all the more restless. He tramped around the stove, and the boards creaked dismally under his heavy frame. "Dang it! Old hermit Budd. Christmas and nuthin' but yore own ugly mug to look at."

Of a sudden he cruised behind the counter and picked up a well-worn notebook wherein was listed the charge account of nearly every homesteader within a range of fifty miles. Budd liked to call these people his flock; he knew everyone well enough to give them fatherly advice. He shared their troubles.

In good seasons he collected his bills. In bad years he asked for nothing and extended their credit far down into the red margin. He thumbed the pages over, critically casting up the individual bills.

Billy Dentler, now, had made a great fight and nearly cleared off his obligations. On the next page was Mary Cappell's rendering—a list rather long. She was fighting it alone. Old man Budd sighed. I give her credit fer a lot of gumption, but I wish she didn't have so much vinegar in her tone when she talks to me. Fact was, adversity had only raised this middle- aged woman's temper. It had been only a careless word with the jovial Budd, but in consequence Miss Mary Cappell had given him a piece of her mind. The only human being within fifty miles that wouldn't speak to an old codger of a storekeeper. Budd, mourning, perused the pages. The gal's got too much false pride.

He dropped the book and stared in heavy disfavor at the row upon row of canned goods that ran in serried ranks along the shelves. That stuff ain't no good up there. Ought to be in people's stomachs. I reckon right now there's families out there in the cussed wind an' snow who'd feel a mite more cheerful for a can of pork an' beans. Jest snowed under an' facin' a fair to middlin' New Year.

THE bright idea struck him like a falling roof. Budd was

not a man given to bright ideas; his thoughts moved usually in a

sort of elephantine majesty. So it was only the more dazzling and

brilliant to have this bright and happy scheme spring full born

into being. By Jeeminy! If that young sliver of a Bullit can

buck snow, so can I! Santy Claus Budd! Well, by golly! He

lost his moroseness in a moment. He forged around the stove two

or three times, chuckling and slapping his sides in a kind of

glee. Santy Claus Budd! Guess I'm fat enough to make two er

three Saint Nicks.

Yes, sir, it was a wonderful scheme. Just pile a lot of that truck in the buggy and start out to visit some of the snowbound people on the prairie playing Santa Claus. Put a little cheer into a darkening Christmas Day. Transfer those gaudy-colored cans to where they'd be of more use. Perhaps he would find someone on the long road who needed company as badly as he needed it. Trade misery, he reflected happily.

He got busy right away. Taking out several empty boxes, he began to pack into them a shrewd assortment of stuff. Tomatoes and beans—the homesteader's mainstay—apricots and peaches, spuds, tobacco for the men, and—rummaging through the glass jars on the counter—horehound and peppermint candies for the women and kids. The further he progressed on this philanthropic chore, the merrier did he turn. By and by he had four or five boxes well loaded. He stared at them with a childish glee, then went out to the barn to hitch the buggy.

"You pore hoss," he commiserated. "Ain't no kind of Christmas for you. But you'll shore like yore oats when you git home."

He drove to the front and packed in the boxes. By now the spirit of the thing was infusing him with all sorts of ideas. "Old Santy Claus Budd," he murmured. "Got to have some jinglin' bells, that's certain." So he went back to the barn, fished out three old cowbells, and tied them together. Then another, more sentimental, emotion moved him. He took the axe and fought his way to the edge of the jack pines. Somewhere in the white and blinding mist he found a little tree, standing no higher than his waist, a scrubby, runty little seedling, to be sure, yet with its green branches symmetrically tapering from bottom to top. He cut it down and lugged it to the buggy.

He had the tree. It was something more important than canned goods or jingling bells—symbol of peace and good will, of Christmas and a thousand intertwined memories. Under its spell Budd made one more trip to the store, this time for two tallow candles. Then he wrapped and tied a blanket around his horse's body, pulled up his own fur collar, and tightly wound the robe about his feet. "Git along, Toby. Gosh, this is goin' to be a rip-snortin' Christmas!"

He turned off from the Bend-Klamath Road and climbed over the hummocks and the drifts of the road that led through the jack pines to the prairie beyond. The horse tugged at his burden, slipped, and stumbled. The wind whistled through the forest, fretted at the buggy, and whirled down the ice-edged pellets of snow. Budd did not mind. He was thinking of his youth in a far- away Pennsylvania town. The sleigh bells would be echoing pleasantly up and down the roads now, and the church bells would be tolling. It reminded him, vaguely, of a carol he had as a boy sung under the neighboring windows. He cleared his rusty throat and tried a bar:

Christmas time, happy time...

"No, you danged fool, don't try to sing. It ain't yore strong point."

AFTER a half hour's travel he found himself beyond the

pines. Through the white mist he saw a light cheerfully winking

out of Billy Dentler's house. A well-filled house, that one: the

Dentlers were young, but they had a brood of four. Budd chuckled

and drove right up to the door. He pulled out the cowbells and

shook them with his heavy arm.

They made a great dingle-dongle. To this jovial man's uncritical ears they created a sweet, harmonious music. A set of dogs ran around the house and howled. The door opened, and the family stood there, looking at him.

"Old Santy Claus Budd come to roost!" bellowed the dispenser of good will. "I left the sleigh home! One of the reindeer got a spavin comin' over the moon, and I had to put Toby in the harness. Jest as well, jest as well! Here's some-thin', folks, to keep the stomach full and the blood warm! Ain't it wonderful weather?"

He cruised into the house, a great hulk of a man covered with snow, and bringing with him a heartiness and a kindliness as big as all the prairie. His round, paunchy face was whipped as red as Saint Nick's himself, and his eyes were beaming when he slid the precious sticks of horehound into the chubby, clutching fingers of the children. They shouted in glee. Mrs. Dentler cried and kissed him, while the bronzed young fellow who bore the brunt of the struggle in the battle for land and shelter pounded Budd on the back. "Take off your coat, draw up to the fire. Just in time for supper."

"Santy Claus stay fer supper?" cried Budd. "No, sir, I can't. Got to reach a heap of folks before the bag runs out. Shucks, folks, you're plumb too happy for an old-timer like me to come in. Christmas is jest for the family to enjoy." He backed out and tucked himself into the lap robe. "Go along, Toby. Ain't it a great Christmas?"

SO in turn he dispensed his gifts along the widely

separated line of homesteaders' shanties on the prairie—the

Christoffersons, Ralph and Grace Olmstead, Nick Carteret, the

Hunters, Jim and Mary, Pete Farrell and his houseful of folks,

the Tabors, the Simpsons, and Old Man Cruze. One by one he flung

the empty boxes in the snow. The little supply of horehound

dwindled to two sticks, and only a few cans of food rattled in

the bottom of the buggy. But the pine Christmas tree still stuck

its tip in the back of his neck, and the candles nestled in his

pocket. He had found no place yet to put that tree where it was

really needed. "All them houses were plumb sufficient to

themselves," he muttered a little sadly. "Man an' wife and kids.

A little to eat, and a fire to warm by. What more can anybody

ask? Of course, they all wanted me to stay. But somewhere in

these parts they ought to be some one who's plumb lonesome like

me. Christmas tree, shore looks like I'll have to pack you back

to the store an' set you up in the kitchen."

The road made a right-angle turn. Toby, the ever faithful, turned sharply in the snow. The buggy dropped perilously on one side and struck the bottom of an old irrigation ditch. "Up an' comin', hoss," said Budd. "Pull out like a good boy." The horse pulled. The right wheel cramped suddenly. There was a splintering of wood and a crash. The wheel buckled under, and the body of the buggy canted on its side.

Budd slid unceremoniously to the ground, heaved himself up, and looked at the wreckage. There had been a deep, narrow furrow in that ditch which, covered by the snow, had pinched the wheel as it swung outward; a little strain on the hub, added to Budd's two hundred and twenty-five pounds of bulk, did the rest. The storekeeper brushed the snow from his shoulders and looked around. It was growing quite dark, and the force of the storm, though not stronger, made a greater impression on the man and beast alike. Cruze's place was three miles back. The next and nearest place...

Budd's face was rueful. "Toby, hoss, if my eyes ain't wrong that leetle light off to the right is Miz Mary Cappell's light. And, gosh, she don't like us for sour apples."

It was a fact. Ever since Budd's last unfortunate remark to Mary Cappell—some good-natured, brusque sentence, no doubt—that lady had made it more than plain that she cared less than nothing for his company. Still, the situation was not promising. Out in the open prairie a bitter wind bit into the flesh like needles. There was a useless buggy and a long journey back to Old Man Cruze's. Budd sighed in resignation and unhitched the horse. Reckon this is goin' to be unpleasant but necessary.

HE gathered up the last of the Christmas gifts in a box

and urged the horse onward. Then he stopped, dropped the reins,

and went back. Darned if I leave this tree after leggin' it

plumb from home. So he hoisted it on his shoulder and again

aimed for Mary Cappell's.

He left the patient horse and advanced to the door. It took just a little reflection to knock on that door. He heard a plain "Come in," sighed again, and pushed open the portal.

"Miz Cappell, I'm shore sorry to intrude. Busted my buggy. My hoss and I'd certainly appreciate shelter."

He made a strange sight, standing on the threshold, covered with snow, and a face that was cherry red; one big arm cuddled the box of provisions, the Christmas tree slung over his shoulder. The woman had some reason for the silence she maintained during the first awkward moments of his entry. Had Budd been a sensitive man he would have felt it more keenly than the storm. The plain truth is that he had his attention on other things.

He saw Mary Cappell pretty clearly at that particular time, a medium-sized woman not far beyond the forty milestone, still carrying the rather even and good-looking features of her youth. She had elected to battle this country alone and, not being particularly successful, had nailed down her guns, summoned her pride, and gone on short rations rather than run up a bigger grocery bill at Budd's. The single room of the tar-papered homesteader's house was as cozy as it was possible to make it. There were chintz curtains on the windows and cupboards, magazine pictures on the walls, and little paper doilies on the two tables. But—and this was the object of Budd's shrewd glance—there was mighty little oil in the dimmed lamp, not much wood in the wood box, and a scant row of sacks and cans in the cupboard.

"What did you say, Miz Cappell," ventured Budd by way of gentle reminder that he had asked for admission.

"I don't suppose I could refuse you in such weather," said Mary Cappell in no kindly tone. She held herself tightly together and her head high.

Budd was not so dense as to miss the undercurrent of that remark. He promptly turned around. "Oh, no, Miz Cappell, I ain't wishin' to intrude on nobody. I'll jest mosey back to Old Man Cruze's."

"Oh, stop that nonsense," she answered impatiently. "Of course you'll stay. I'd be heartless to drive a dog out in this weather. Put down all that stuff and take off your coat. And, if you don't mind, leave the shrubbery outside."

Budd went out into the night, grinning to himself. Wasn't she a tart creature, though? All the courage in the world, but much too much of false pride. This, he communed, leading the horse to the barn, was going to be a plumb interestin' evening. He took off the harness, sought vainly for a little hay, and returned to the house. The lamp wick, he noticed, was turned higher, and she had just filled the stove with wood.

"Are you hungry?" she asked. Budd, thinking again of those bare shelves, hastily said, "No." His big frame was really in need of fuel. He dragged a chair to the fire and hovered over it.

"Awful cold evenin', ain't it?" he ventured.

"Yes," answered Mary Cappell tersely. There the conversation lagged. The wind whined around the corners of the shack, and the fire glowed in the grate. Time passed heavily laden with silence. The woman was most determinedly looking at the walls. Budd, leaning far over, repressed a grin. His eyes beamed.

"Ma'am," he said hesitantly, "I been playin' a leetle game tonight. Santy Claus you might call it. Been comin' down the road with a few presents for all the people I know hereabouts. Jest a leetle Christmas present for the folks. I'd take it mighty kindly, Miz Cappell, if you'd accept what's in that box as the season's offerin's from old man Budd."

She bounced out of her chair, and her eyes sparkled with ire. "Mister Budd, you don't have to remind me I owe you money! When I am able, I shall pay you every red cent, with interest. Meanwhile, it's...it's insulting of you to come here and hint about it!"

It took Budd full in the sails. His mouth gaped. "Why...!" Then the natural dignity of the man came to the surface. "Now, ma'am, you don't really think that," he said gently. "I'd be a pore sort to come around collectin' bills at Christmas time...or even hinting."

She was not to be appeased that easily, although the edge had gone from her anger. "I know I owe you money. Don't worry, you'll get it."

"Wish you'd stop thinkin' about money on a night like this," he said plaintively. "I ain't. Shucks, ma'am, every man, jack, and baby owes me money in these parts. Part of the gamble of homesteadin'. You don't owe me nothin' compared to some. I ain't worryin'. My store's open to all, any time, all the time, regardless. People got to live."

"Nevertheless," she said, "I know what you're thinking. You're thinking a woman is foolish for trying to homestead alone. I know you think it. You as much as said so the last time I came to your store. A very cruel, uncalled-for remark. I had thought you my best friend. That showed me otherwise. I'll teach you people different before I'm through with this prairie!"

"Never said you was foolish," Budd stoutly asserted. "You as much as said so. A very cruel remark."

Budd searched his memory. What remark had he made? Soon he was grinning like a Cheshire cat. The woman stormed at him. "Are you laughing at me?"

"Haw! No, ma'am, not at you. Was it the thing I said about it bein' a scandalous waste for a woman to be single when there was plenty of eligible men around?"

"I do!"

"Shucks, you needn't take that to heart. An old feller's joke."

"It didn't sound so to me. I'll show you whether a woman can win her way or not!"

Budd became stern. High time to pull in the reins. "See here, now, Mary Cappell, you an' me was gettin' along real handsome until you figgered I'd made that break. You're a plumb spirited woman and full of ginger. But you got too dang much false pride, an' it's high time someone told you. Got to take things as they come in this country. If you don't, all the pride'll be knocked from your body by old man Adversity. It's a tough struggle, an' you got to be a little meek about facin' the prairie. An' when people joke, you oughtn't turn up your nose 'cause it sounds a mite crude. We're all bed-rock hereabouts, all strugglin' to make things go. If we sound like we wasn't quite polite, it's our privilege. We don't get much chance to practice humor, an' mebbe we ain't so good at it. Now you be decent an' civil."

She was silent and, Budd saw forlornly, not altogether convinced. He got up from his chair, went to the door, and opened it enough to pull in the Christmas tree.

"What are you doing?" she asked.

He grinned a little apologetically.

"Carried this thing all the way from home, thinkin' I might find some place it'd come in handy. Got a hammer 'n' some nails?"

He tacked the base of the tree to the floor and pulled out the two candles. "I figgered we'd jest sort of light the tree up. Make it more like Christmas." Taking his pocketknife, he cut the candles in small lengths, dug out the wick and fashioned a point. He put all the pieces on the table and lighted them with a taper from the stove, Then, gravely performing a ceremony, he took the first candle to the tree. "Jest to remember folks we ought to remember. This one I'll put on the top where it'll burn plumb bright."

"And who is it for?"

He stared at it solemnly, unwinkingly. "Mary Budd...my wife...died when we was both pretty young."

"Oh." Then, after some time: "The next one will go right below it, Mister Budd."

He fastened it to the tip of the limb. There was, after all, a streak of delicacy in this great, bulky creature. He asked no questions, never attempted to pry. Standing back, he gave it the same solemn respect. "To someone," he said, "someone you loved."

"Yes," she answered quietly. "To someone."

He put three or four of the candles in his bear-like paw.

"That's for those we ought to remember. Makes us a little sad, mebbe, when we oughtn't to be sad. Christmas was made for people to enjoy. So I reckon we'll just stick these in roundabout for to light everything up." One by one he disposed of them. "Now," he said, "ain't that plumb pretty to look at?"

"If I've said things that were too harsh," she ventured, "I'm sorry. It's...it's hard on the nerves to live all alone."

"Haw, don't I know it?" He slapped his big hands together. "Ain't natcheral for people to live alone. Guess I'm a great, big, galumtious sort of fellow. Sometimes makes you think of a steam shovel, mebbe."

THEY stood rather close together, looking at the

glittering tree. The fire popped merrily in the hearth and a

warmth and comfort invaded Dave Budd's being. It was plumb nice

to be here. He felt at home, felt rested. The tree had done its

work after all. He had found one soul as lonely as his own.

Perhaps he had not turned the knob of the door tightly enough. A great gust of wind slatted on the roof and tore around the corners with a gasping sound. A finger of that wind rattled the door, gave it a huge push, and flung it open. The thing banged up against the wall with a sharp crack. It was so unexpected that the woman, nerves tight and uneasy from so much living alone, jumped quickly, turned, and found herself right squarely placed in Budd's arms.

He looked down at her in huge surprise. "Why, say, Mary, you're awful pretty now!" And, in the manner of gay blades the world over, he put his arms about her gently, stooped a little, and kissed her.

After all, she was a woman. The kiss seemed not unwelcome, for she made no move to draw her head away. Thus they stood, two middle-aged people embarked on romance, going about it somewhat stiffly, it is true, but nevertheless repeating the ancient story. Budd's hand was awkwardly hanging over her shoulder, and he had failed to meet her lips squarely. It made no difference. They stood still until the woman, shivering, drew away. "I'm cold, Dave."

He cruised across the room and slammed the door. "Mary, supposin' you open a can of these beans here and put on a leetle coffee. Come to think of it, I'm hungry as seven boiled owls. Christmas! Ain't this the greatest Christmas you ever had?"