RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

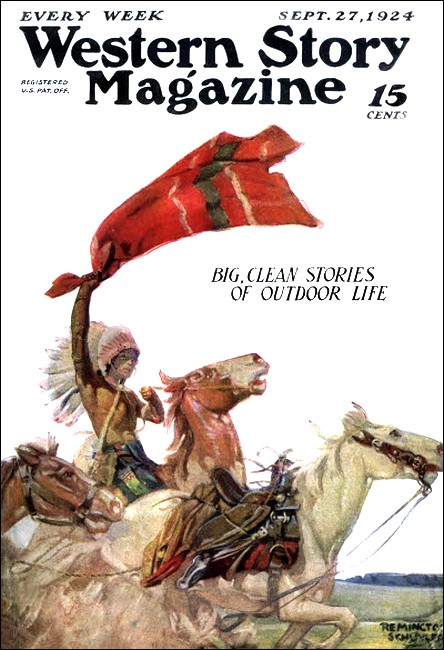

Western Story Magazine, 27 December 1924, with "Stubborn People"

OLD man Budd sat on the porch of his Burnt Creek store, watching the shimmering heat waves that rose out of the jack pine forest and trailed across the small sand-floored clearing. A lazy drone pervaded the air, broken by the snapping of myriad insects and the impalpable, shutter-like beat of the blazing atmosphere.

He had a habit of reflecting on life. Every act in a man's life, he reflected now, was affected by every other act. There was no beginning and no end. Just an everlasting onward march. Take Jim Hunter, for example.

Budd's impassive face lightened. "Think of the devil an' he's sure to pop up." From the north leg of the Bend-Klamath Road rode Jim Hunter, a tall and supple fellow who, even in the saddle, seemed unable to bend his shoulders.

"Stubborn as a mule," reflected Budd in admiration. He waited until Hunter had reached the porch and led the horse into an ineffectual patch of shade before vouchsafing welcome. "You'd save a lot of energy, young fella, if you'd just slouch in the saddle when you're ridin'. That's advice from a broken-down cowpuncher. This ain't no parade."

Hunter stepped up on the porch. The effect of his stature was heightened by the way he carried himself and the seasoned leanness of his body. The struggle on homestead land had definitely left its impression. With some men the abrasion of weather and work affects only a general hardening of features. In Jim Hunter it brought out the original tenacity of his nature and left decisive lines on the berry-colored face. A flash of humor widened his eyes.

"There's no use trying to save me trouble, Budd. Takes fire to burn a fool. I need some coffee and beans."

"Huh." The storekeeper hoisted himself from the chair and ambled into the dark building. "There's a letter. Mebbe you'll want it afore the beans."

Hunter took it with unrestrained eagerness. The gravity dropped from him like a mantle. It seemed he could not tear away the envelope quickly enough. Dave Budd, sharply watching, saw the young man's eyes race down the written page with actual avidity, but as quickly the face turned expressionless again. Presently he crumpled the page in his fist, scowling—so bitter and unforgiving a scowl that the storekeeper clucked his tongue and dumped the provisions on the counter softly.

"Anything else?" he asked.

"No! There isn't anything else," muttered Hunter. "There never is."

He stared out of the door upon the sun-scorched clearing. His mind was far from Burnt Creek.

"I mean in the line of grub," added Budd dryly.

That brought the young man back. "You old goat, quit reading my mind."

"I been called a lot of things in my time, but I pause at the term goat," grumbled the storekeeper. "I figger some day I'm a- goin' to quit tendin' store fer a bunch of sassy homesteaders. Take your grub and git."

Hunter stalked to the porch, dumped the grub in his saddlebags, and climbed into the saddle.

"If a man was in his right mind, he'd never come to this god- forsaken land."

"Road's plumb open. You ain't tied to that land. If you don't admire it, why'n't you just sashay out?"

"Same reason you've stuck to this dump for twenty-five years," retorted Hunter.

The two traded sober glances. Budd nodded. "Guess you're right, son. We're sort of spellbound. Gets in the blood, I reckon."

HUNTER turned his horse to the road. In a moment he had

disappeared through the jack pines. Budd settled in his chair

after securing a fresh cigar and reverted to his original line of

thought. Jim Hunter now had been a homesteader three years and

wore the same hard-bitten look that they all carried. It was

partly the result of fighting the land, but it wasn't wholly so.

Jim had come from Portland with the same tight lips and the same

stubborn carriage of body. Three years had done a great deal in

seasoning and tempering the body and wearing away all softness.

The essentials remained untouched. Regularly he came to Burnt

Creek for supplies and mail. Regularly he received a letter in

the same feminine handwriting, which he opened always with a

brightening of face and crumpled later with a scowl that seemed

to cover hurt pride and forlorn hope. Those letters, evidently,

demanded something he would not give, for he never sent an answer

through Budd's little post office.

The storekeeper reluctantly left the chair and wandered back to his kitchen. The sun blazed up in the sky, intolerably scorching. Budd viewed an empty pitcher and set to work at making a supply of lemonade against the greater heat of the long afternoon. A few beans, some hard bread, and a dish of canned peaches served for dinner. Then, with a fresh cigar and the lemonade at hand, he settled himself in the sultry shade. All things in Dave Budd's philosophy came to those who waited—provided the waiting was mixed with a little judicious assistance.

THE afternoon was not to be lonely. He had just started

on the lemonade when the sputter of the Bend-Klamath stage motor

reached him. The vehicle swayed out of the forest, climbed the

ruts of the road, skidded perilously amid a shower of sand, and

brought a boiling radiator nose to nose with the porch. The

driver had a passenger this trip. A woman it was, veiled against

the dirt and sun. Teddy Hanson climbed away from the wheel and

helped her to the porch.

"Aw," he said, "now what's the good of stoppin' at a horrible hole like this, ma'am? Gosh, think how lonely I'll be all the way to Klamath."

"Flattery," said the girl. She drew back the veil, and Budd, greatly puzzled by this visit, found himself looking at an extremely pretty mouth and a pair of hazel eyes that could, when they pleased, be very friendly. Some shade of dark hair strayed pleasantly down a white temple. "Is this Mister Budd?" she asked.

"That's him," growled out the driver. "There's a lot of circumferance, you see. He gets it sittin' on the porch of this so-called store."

"I wouldn't listen to such slander," replied Budd. "It's the heat makes him that way. But I mistrust you've got to the wrong place. Ain't hardly anything here you could stop off for. It must be Klamath you mean." He could not help noting that it was not the friendly eyes nor the pretty mouth which most attracted him, as it was a firm little chin with the dab of freckle on it and an Irish nose. She'll be wantin' her own way, he silently prophesied.

"No," she answered. "It's Burnt Creek."

Teddy Hanson boosted the girl's trunk onto the porch, obviously disinclined to leave. She settled the matter by paying him. "Thank you." The inflection was as much as a dismissal. Teddy shot a glance of envy toward Budd and climbed into his seat.

"It's a wonder you wouldn't fix the road in front of your shack," he shouted above the clatter of the engine.

"That sand flea can burrow where it won't climb," retorted Budd. A cloud of sand shot from the wheels and, when the dust settled, the stage was gone.

"I dunno how that thing sticks together," he said. "It drinks sand an' runs on grasshoppers. They's a hundred dollars' worth of bailin' wire in it." He saw that she had lost spirit and was staring wistfully at the road. "What'd you say you were after, ma'am?"

"They told me in Bend that you'd help me. I I...I'm looking for a homestead here."

"A homestead, ma'am?"

"Never mind how I look!" she cried. "And don't try to argue me out of it! I've argued all the way from Portland, and it's settled. If you won't help me, I'll have to get someone else. I want a homestead near Burnt Creek."

"Why near Burnt Creek, ma'am?"

"For...for reasons."

THERE was metal in her. She wore clothes that stamped her

as a refined city woman, and her hands and clear skin were plain

enough witnesses that she had never trafficked much with spade

and bucket. Still, Budd did not make the mistake of arguing. He

saw her determined little chin with the dab of a freckle on it.

She was another of those stubborn people...such as made good in

this country. They never knew when they were licked.

"Why, sure, I'll help you, ma'am," he agreed affably. "Most everybody comes to me sooner or later, around here leastwise. But it's powerful hot right now. Come in an' have some lemonade."

It was a great deal later, when the courtesies were dispensed with and the subject of land well talked over, that Budd thought of the Hazen place. "I been thinkin'," he said, spoiling a new cigar, "that you'll be all by yourself. It's a hard life any way you take it an', if you could get near other folks, it'd be a great boost. I've located durn near every other family in these parts, an' it strikes me there's a nice section about an hour's ride from here, adjoinin' Jim Hunter's place."

Her head came up of a sudden, and a sparkle of triumph set her blue eyes to shining. "That's the place I want!" she cried.

It staggered Budd. "Why, ma'am, how do you know? Mebbe you wouldn't like it at all. Better wait till you see it."

"I do know! Is there a house on it?"

"Ordinarily the government don't furnish houses," said Budd with the suggestion of dryness. "But it so happens old man Hazen took this up an' got plumb discouraged. He went to Bend. You can take up the rights fer next to nothin'. I'll see about that. There's a house, well, an' barn on it." She sprang from the chair. "Mister Budd, can't we go right over and move in now? I want to get started."

Her face was tinted with a pink excitement and her mouth, which Budd decided was about as kissable a one as he had ever seen, was puckered in determination. She was finding a great satisfaction in something. The puzzled storekeeper watched her. "Why, I reckon you could, but..."

"But!" she exclaimed. "That's the only word I've heard lately! I don't want to hear any more of it. I want you to help me file the necessary things and help me move. Whatever it's worth, I'll pay you. But you've got to help. Can't we start right now?"

The storekeeper found things moving too fast, and he promptly vetoed the suggestion.

"We ain't goin' no place at two o'clock in the afternoon. Why, ma'am, people don't travel through them jack pines this time of day unless it's powerful necessary. Terrible hot. 'Bout four- thirty we'll start. Meanwhile, we'll be collectin' some grub an' tools."

She seemed to acquire more and more energy. The delay fretted her, and she moved restlessly around the store, choosing what she needed from the shelves. There were sundry implements of which she knew nothing at all, and Budd explained them. She listened quite carefully, a wry expression now and then tempering the determination. Budd was compelled to admire the way in which she accepted his picture of homestead life. None too rosy did he paint that picture, either. He wanted recruits for the land, but he wanted them to be disillusioned before they started residence. Once she stopped him.

"You're trying to discourage me," she said.

"Huh. I been here in this country twenty-five years, an' I'm tellin' you as straight as I can. The land grows on them as can stand it. For the rest, it kills or drives out."

"It won't scare me. What others do, I can do."

He silently applauded. "You can go out an' live on the place without hindrance while I sort of fix up things with Hazen an' the land office. You can go to Bend later."

THE sun blazed downward, and after four o'clock Budd

ventured from the store, hitched his buggy, loaded on the trunk

and duffel, and began the journey through the jack pines with his

passenger. He watched her from his heavy-lidded eyes, waiting for

some sign of weakness. In the dwarf forest the heat scorched

them, and the sand rose out of the road and cascaded from the

branches. It was a dismal entrance to a hard land. However, if

the girl felt any discouragement, she kept it well to herself,

hands folded in her lap and sitting erect in the swaying seat. So

Budd turned to casual topics, directing her attention in his

kindly way to the things she must do and expect.

"Ma'am," he said finally, "if I ain't too personal, just what makes you do this?"

It struck tinder. He saw a spark flash. "Because I want to show him...people...that I'm no butterfly! That's why! And I will do it!"

There was, then, a man involved. Budd, seeing partial light, moved away from the subject. They drove in silence while the rutted highway wound slowly through the heart of the pines, passed sundry trails, and came at last to a vast open plain over which the sun shed a blood-colored glow.

"Purty, ain't it?" asked Budd, wistful pride in his voice. "See yonder house? That'll be your nearest neighbor, Jim Hunter. A mighty fine boy. You'll do well to know Jim."

"H'm."

"Yes, sir. Jim's the stubborn kind. Hard as nails an' never says much, but that's the only breed who'll survive this country. He'll help you."

The buggy turned off the road and went bumping over the flat land. They passed a corner fence and in time drew up at the door of Hunter's house. Budd called out: "Hey, Jim."

The girl seemed to become very still, and the storekeeper, turning, found a flutter of excitement again in her eyes. Jim walked from his place, stooping slightly to pass the upper sill.

"You're goin' to have a neighbor, Jim. I'm locatin' her on the next place. You'll kinda watch..."

He got no further and found himself thrust completely out of the picture. Hunter strode toward the buggy, the soberness quite gone from his face.

"Why, Mary, what on earth...?"

"Don't make any mistake," she broke in. "I've come for that apology."

Budd raised a hand to a sorely puzzled head. The girl was sitting like a statue, her fingers interlaced in her lap, her chin held a little higher than usual, the delicate pink spreading slowly. The excitement was gone. Budd had the idea that it was suppressed only by an effort. Hunter stopped dead. "What?"

"I said I've come for that apology, Jim."

"Now why," he said angrily, "did you come all the way out to this hot and dusty place? Budd, you ought to have more sense."

"I asked him to bring me." She stamped a foot against the buggy floor. "Jim Hunter, don't you boss me. The time's past for that. I'm going to make you take back what you said that time if it takes me ten years! If writing letters won't do it, then I'll try farming. You might at least have answered my letters out of courtesy."

"What's all this foolishness about her living on the next place?" demanded Hunter, turning on Budd with a scowl. "Have you lost your mind? Great Scott, a woman can't fight this desert, and you of all men ought to know it!"

Budd made an ineffectual gesture with his hand. There had been no preliminary warning to all this. The girl's mouth was puckered together, and she seemed on the point of crying from sheer anger. Budd was about to mention the former Grace Lewis when Mary burst out: "Oh, if I were a man, I'd make you apologize right now! You can't bully me, Jim Hunter! I'll not stand for it, you hear? And I'll show you if I'm a butterfly! Go on, Mister Budd."

The storekeeper was only too glad to escape. The end of the reins smartly thwacked the horse's rump, and they bumped over the uneven ground toward the Hazen place a quarter mile on. Budd threw a quick glance behind him and saw Jim Hunter rooted in the same spot, arms akimbo, face furrowed. If he knew anything about it, Budd reflected, there was a young man who would soon wish a strong interview.

He discretely held his peace and, when they reached the house, began the job of packing the trunk and various tools and utensils inside. When he had finished, he found the girl seated on the trunk, surveying the walls with plain dismay. Truly, it was a sight to discourage a mortal woman. A bachelor originally had lived here, a bachelor who had found the job of keeping up externals too great, let alone the niceties of housekeeping. The floor was littered with dirt; the walls and ceilings were bare and unpleasant. A stove was half dismantled. A chair and table were overturned and partly broken. A bunk had once stood against a wall but now had parted company from itself.

"Well," said the girl, taking off her jacket, "the first thing's to sweep."

The storekeeper was ready to shout. Spunk! She had more of it than a dozen men. Heretofore he had nourished misgivings, but now he moved solidly to her support. Those nice clothes and white hands didn't mean anything.

"Yes, ma'am," he agreed. "We need a new deal. You just take a bucket and go out back fer some water in the well. Meanwhile I'll tackle the broom, it bein' a dirty job."

Broom and water, hammer and nails, elbow grease and much talk—by these means and two or three hours' time Budd and the girl transformed the place into a passable shelter. There had been some wood left. Budd built a fire and cooked a meal while the girl added a touch here and there to the bare walls. It was after dark when Budd climbed into his buggy and started for home.

"Well, I reckon you're dog tired. It's easy to sleep out here. An' that gun I give you will scare away most anything that walks or crawls. Ain't nothin' to be afeerd of, anyhow. In case anything should happen, you..."

"I'm not asking him for any favors!"

He suppressed a grin and continued as if there had been no interruption. "In a few days I'll bring you a collie dog an' a hoss. Then you'll be fixed. Meanwhile you just set tight an' git organized. I'll see Hazen an' the land office. G'night."

He drove away, bent for the pines and Burnt Creek. But if he thought to avoid Jim Hunter, he was mistaken. The young man was camped outside his house, and Budd saw him move through the dark toward the buggy. The storekeeper sighed a little and came to a halt.

"All right," he acquiesced wearily. "Go on now an' say what's been burnin' you."

"Of all the old fools!" rasped out Jim Hunter. "You know very well she can't stay out here! It's impossible. What can a woman do? Here I work my head off and just break even. How do you expect her to get by? Just because she's bent on..."

"What should I have done?" asked Budd gently.

"Told her to go home, of course. Discourage her from such a crazy idea."

"Huh. No wonder you 'n' she quarreled. Don't you s'pose I did some arguin'? Huh? It was like talkin' to myself. If I hadn't brought her, she'd've up an' walked out on the darn desert by herself. Got to handle her another way. She's as stubborn as you."

Hunter groaned. "I know it. She's always been like that. If she gets her mind set, nothing short of an act of God can change it. But she can't stay!"

"I wouldn't be so durned certain," snapped out Budd. The late hour and the prior excitement had put him a little out of humor. "She seems plumb able to take care of herself. I've seen women get by on this desert. Grace Lewis did quite well for herself till she married a man just like her! A woman can beat a man all hollow fer endurin' things."

"It's not only that," broke in Hunter. "It's not safe. All sorts of queer ducks roam these places. A lone woman just invites trouble. There's Bottle-Nose Henderson, for example. Great Scott!"

Budd scratched his stubbled chin. He, too, had thought of Bottle-Nose. It was a prickling thought that remained in the rear of his head, vaguely disturbing. Yet here was Jim within a short distance of Mary. If she called for help, he'd be over in a jiffy. "Ain't nothin' to worry about. Giddap, Toby. You people fight it out atween you."

"There's not going to be any fight...or anything else!" bellowed Jim.

Budd had no answer for that, but a mile later, when the pines swallowed him, one small phrase came out of all the wonderment: "Son of a gun, just look what's happened to us today!" The peace—and the monotony—which had enfolded him during the last hot summer month was gone. Life was just one dog-goned problem after another. That's what made living endurable. "Giddap, Toby. We got to figger around this somehow. There's a couple plumb in love with each other an' wantin' to make up. But they'd die afore they'd admit it. Got to fix that."

HE found as the week went along that all ordinary

conciliatory means had no effect. The quarrel had gone too far,

endured too long. The battle had arrived at a stage of siege. It

worried him, for the robust storekeeper was not a man to stand by

and watch the tide carry his people downstream. Faith had made

him the prophet and leader of the homesteaders. He loved them and

fought for them, took an unreasoning interest in their small

affairs, argued with them, cursed them, and at the last word,

when it seemed they could no longer struggle against the eternal

hardships, gave his own time and money to keep the small flame of

courage in their hearts. They were all, Budd believed, in a

common brotherhood, striving for a common happiness, and every

sorrow and discouragement they suffered was sure to find its way

eventually to his own big heart.

He had no means of knowing the nature of the quarrel, but still he worked shrewdly to dispel it. The day after the girl had settled on the homestead, Budd saddled the gentlest horse of his lot and sent it over to her by Slivers Gilstrap, a passing cow hand.

"You tell her, Slivers, that I'll be over after a while with the necessary doodads, an' that she'd better ask Jim Hunter to fix that lock on the door."

LATE that night Slivers came back with blood in his eye.

"Say, you old galoot, what'd you go an' tell me to tell her that

for? Minute I says it she flies offn the handle an' says she

ain't askin' Jim fer nuthin'. I thought mebbe he'd insulted her

an', bein' a gentleman, offers to shoot him er hog tie him, er

anything. Dog-goned if she didn't larrup me, then."

Thereupon Budd went to Bend and rode back to the girl's place with filing papers, another sage move up his sleeve. But he had no chance to act upon it. Mary, dressed in some kind of old clothes and already freckled by the sun, met him with fire in her eyes.

"Mister Budd, I wish you'd go over and tell Jim Hunter I forbid him coming on my land! He's been here twice trying to browbeat me. You tell him I don't want but one thing from him, and that's an apology. Otherwise I'll use this pistol. I will!"

She flourished the heavy weapon in her hand, and the storekeeper, suppressing a chuckle, noted that she used both hands to raise it. It would have been disastrous to offer advice then.

"Mebbe," he gravely offered, "I'd better notify the sheriff to arrest him fer trespassin'."

"No, oh, no! I wouldn't do that. But you tell him what I said, will you?"

So Budd, inwardly chuckling, went to Hunter's place, only to be motioned away. "Get out of here, you old goat. I won't listen to any more of your ideas. You're the cause of all this."

"The most ungrateful thing in the world," opined the storekeeper, returning to Burnt Creek, "is mixin' in family troubles. Men've been killed fer less. But if I'm to be hung, I might as well be hung fer somethin' good. Patch that up somehow."

MAN and woman were crowded from his mind in the

succeeding weeks. Events in the sparse Central Oregon country

move with the same irregular frequency as elsewhere. Out of a

serene sky broke seven kinds of trouble into which Budd was

directly or indirectly drawn. For one thing, threshing season was

on full blast, and every able-bodied man gave his services. This

was communal law. Then the road commissioners in a frenzy of

economy—just before election—decided to leave

unimproved a more or less impassable stretch of the Bend-Klamath

Road. The storekeeper, being apprised of it, rode to town in a

fury and shocked those commissioners out of their economic

resolutions. He fought for his people and his land ruthlessly

and, being a power in his own right, won. Hardly had this

subsided when the shadow of Bottle-Nose Henderson fell across the

land.

Bottle-Nose was one of those derelicts for whom society has no honored place. In a more highly organized community he would have been sent to an asylum. Deschutes County tolerated him because he stuck to the open spaces and left people alone. But somewhere on this lone trail the last remaining fiber of reason snapped, and he reverted to the law of the jungle. He ran amuck, terrorizing the edges of the county, and sent unprotected families into gusts of fear. No one seem safe from his swift attack. The sheriff sent out a posse, and they traced his course southward toward the Burnt Creek region by three pilfered houses and several frightened women. This trail was all the posse found. Bottle-Nose had become elusive as well as a highly dangerous character.

It was from him that the storekeeper conceived what seemed to be a sound idea one late summer evening as he jogged homeward. Toby, plodding along in dignified weariness, was startled to feel his master shake as if from ague, something that passed as a chuckle issued from Budd's barrel-like chest.

"If I got caught, I'd sure be hamstrung," mused the storekeeper. "Would lose all my reputation if I got caught an' mebbe git a dose of lead poisonin'. But it certainly oughta bring results."

And results were all that mattered to Budd. At any rate the idea took possession of him. His chin fell forward, and Toby, unchecked, picked a faster pace toward Burnt Creek, viewing doubtless the measure of oats in the stall. A wise horse was Toby, but this time sentenced to a grievous disappointment. On reaching the store Budd went in and returned with his revolver.

"Giddap, Toby, we've got to hustle. Dog-gone it, quit your balkin'! I feed an' pamper you too much, that's what. Git now! Ain't to be fooled with."

After a short argument the sad Toby walked into the jack pines, bound for the desert. Leaving his horse to find the way, Budd relapsed into that reverie which years of solitude had acquainted him. Nor did he raise his head until the last dwarf pine was passed, and he stood against the gloom of the open land.

IT was near nine o'clock. The moon displayed a thin,

lifeless rind in the sky; the countless stars blinked down

without dispelling the shadows. Across the open ground winked two

lights, one from Jim Hunter's kitchen and the other from the

girl's house, both cheerfully beckoning. Budd clucked his tongue

and struck across the open, passed Hunter's place at a good

distance and, on arriving within a few yards of the Hazen house,

climbed out of his buggy.

"Now, you gol-durned animal," he whispered, "stay put. When I come back, it'll be a-foggin'."

He took the revolver from the holster and, under the impulse of an unusual kind of excitement, drew the hammer part way back and turned the cylinder with a thumb. Ten feet away Toby and buggy dissolved into an indistinguishable blur. Budd took a mental line from his horse to both lights.

"Got to place that dog-goned critter," he murmured, advancing.

A heavy boot toe struck a projecting rock, and he balanced wildly, failed to right himself, and fell to the ground. The impact seemed to shake him loose in a dozen vital spots. An immense grunt escaped him that seemed as if it exploded in the air, but that was only imagination. He crawled painfully to his feet and went on until the light from the girl's kitchen window was quite clear. He could see inside the small room but failed to locate her.

"Gosh, I got to see where she is afore I shoot."

He angled aside to get a better sweep of the room. It occurred to him then that he was more or less in the position of a Peeping Tom, and a rod of ice smote his back. "Fer a nickel I'd quit this fool stunt," he said to himself. Then the light was eclipsed for a moment as the girl moved to the front of the room. "That'd be the corner the stove's in. She's safe." He raised the revolver and aimed at the window.

It was not the best idea in the world. Budd began to suspect that earlier in the evening. But his self-defense was adequate enough. Both the girl and the man were too obstinate to listen to reason, and summary methods had to be employed for their own good. They were just like two fighters who struggled long after the original injury had been dead and buried. Now the only thing a man could do with stubborn pride was blast it. What he meant to do was put a bullet through that window and shatter a pane of glass. That would give the girl a much-needed scare, sort of shake her confidence in her own strength. If, on hearing that shot, Jim Hunter didn't rush over to her house he, Dave Budd, would be greatly mistaken in his man. And if that threat of danger, always a welding influence, didn't change their relations, he'd be mighty disappointed. He brought the gun down on the bright window, taking care that the shot would break a pane and bury itself in the sill.

There was, of a sudden, a pad-pad of feet on the ground, an alarming rush of body that went past him, wheeled like a football player, and bore down. Budd's revolver arm fell. A low figure hurtled from the shadows, struck him amidships, closed about him, and knocked him over with the savageness of a hungry cinnamon bear. The storekeeper's teeth rattled. He bit his chin and choked in the sand. A rock struck his head and nearly put him to sleep. Quite instinctively he put up both huge arms—he had dropped the gun—and pushed his assailant off; but before he could take advantage the man had thrown himself back again. A fist smacked against his temple, and a familiar voice reached his half-buried ears.

"You sneaking coyote! Thought you'd raise the devil in another lonely house, eh? Thought you'd scare another woman half to death! I've been laying for you. Next time maybe you'll be more careful in sneaking up on a place. I'm just about going to kill you, you Bottle-Nose skunk!"

It was Jim Hunter on the warpath, mistaking him for Bottle- Nose Henderson. Budd's mind worked in circles, amid a confusion of blows, a ton of sand, and smarting eyes. He had to get out of here in a hurry, no mistake. It wouldn't do for Jim to discover his identity. Jim wouldn't consider him in any better light, wouldn't understand. He had overlooked the fact that the young man would patrol the girl's home after dark and, in patrolling, might see him. The thing now was to make an exit and call it a bad venture.

He stifled a groan of protest. It was a darned good thing Jim had never seen Bottle-Nose and noted the man's skinny shape. The storekeeper raised hands and feet, throwing Hunter back like a blanket, got up, and dashed toward Toby.

By golly, but this was a mess. Look where he'd got himself in trying to do a good deed!

Hunter was on him like a wild cat and down to earth they went, rolling, clawing, fighting, with no words at all to waste. Budd flung the lighter man off, got up again, ran a yard, and was pulled down. Somehow Jim's fists found their mark. Budd felt his nose ache with resentment. In turn he traded blows and heard them land solidly. There was a burly strength in the storekeeper's shoulder, a power which once in the older days had made him top hand of the county. Right now he spared none of it to get clear. But it didn't matter how many times he threw Hunter away, the man was back again, pinning him to earth like a clothes dummy. Each fall hurt the corpulent Dave Budd more than he cared to admit.

"I got to quit smokin'," he said to himself. "Wind ain't no good."

Toby, nearby, snorted. They rolled beneath his very feet, and he moved uneasily. Budd dragged himself and Hunter upward toward the buggy. "No you don't!" panted Jim. "Come back here." Budd, falling, had his face turned toward the girl's house, and he saw a shaft of light spring out of the opening doorway. Somebody stood on the threshold. He wondered if this was actually so or whether the little skyrockets in his head caused the illusion. He was soon enough put to rest about it; for a shrill, terrified scream shattered the air. Hunter's aggressiveness instantly ebbed, and a gasp broke from his hard-pressed lungs.

"What's that?"

Budd's mind attained an unprecedented nimbleness. Somebody had come across the desert from an opposite direction and gone into the house while they were fighting the silent battle. Bottle-Nose Henderson, then! The man was somewhere in the Burnt Creek region.

"Huh," he grunted, "I thought you were tryin' to put somethin' over on me. Thought you was Bottle-Nose. Been trailin' him all day. Leggo, you darned scorpion! This dog-goned darkness! I thought I had him pinned down."

Together they ran across the prairie and reached the open door. Hunter was the faster, and he made a single stride to the far corner where the girl, back to the wall, faced a thin, nondescript creature whose crimson, bulbous nose and slack mouth gave him a particularly vicious expression.

Hunter flung himself upon the man and threw him against the wall so hard as to make the small place shake from rafter to floor. Budd, near done up, was content to watch them fight. Hunter was a veritable wild cat. He beat down the invader's defense and, like a boy who has found pleasure in throwing things, swept his man across the room and slammed him against another wall, overturning a chair and table on the way.

IT was soon over. Bottle-Nose collapsed with a sigh of

defeat, slid to the floor, and whined for mercy. Jim Hunter

strode over to the girl, looking as one just emerged from a mob

attack. His shirt hung in ribbons about his gangling arms. There

were sundry cuts over his face, and his hair was ground with

sand. But nothing could conceal the flare in his eyes.

"Honey!" he cried. "I'll kill that skunk if he's hurt you!"

"Jimmy, what has happened?"

Budd turned his broad back and wryly moved his nose. There was a more or less incoherent explanation and questioning from both and out of it, unexpectedly, came: "Jimmy...I won't ask that apology if you don't want to give it."

"I'm a bum. I give it, Mary. I'm just a stubborn bum."

"You give it! Jimmy! I'll never ask another. And I take back everything."

A great and ponderous silence ensued, broken by the impatient Budd. "Here I trail this fella all day long and then you dog-gone wild cat...look what you done to me."

It was not a very strong story, but Jim Hunter was too preoccupied to pick flaws.

"I'll take Bottle-Nose back with me," continued Budd. "Say, just what was this quarrel about, anyway? Seein's I got so durned involved in it, might as well tell me."

"He called me a useless butterfly, and I had to show him I wasn't."

"Which was after she told me I couldn't do anything worth while."

"For gosh sake," stuttered the storekeeper. "Was that all?" It was certainly queer what small things set people at a tangent. Stubborn people, chiefly. But what great fighters they made. Just the kind to populate this sturdy, harsh land. He fell gloomily to another thought. "Suppose now you'll make up an' go back to town."

"Not on your life," declared Jim. "It's the only place I'm worth anything. Why, I'm happy here!"

"So'm I," added the girl. "That settles it."

Budd was forced to a rare smile and looked like the cat who had swallowed the canary.

"Well, I'm sure sorry my little peace efforts didn't work. Took Bottle-Nose to turn the trick. So long, folks."

It was later, entering the dark forest with his prisoner, that he lifted his face to the dim, star-scattered sky and gave thanks. Some day this country would blossom under the hands of these vigorous and clean-chosen people. Some day!