RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

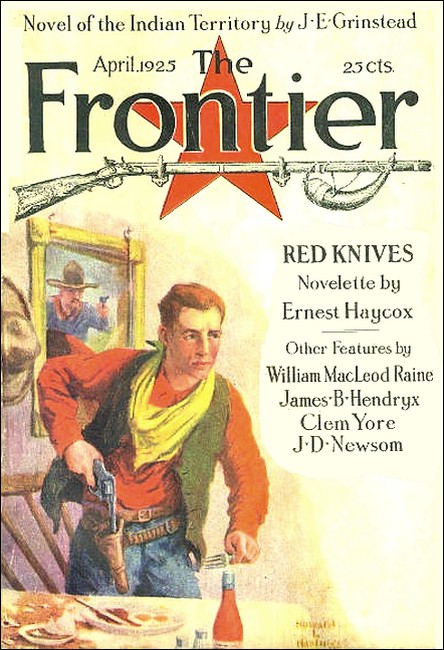

The Frontier, April 1925, with "Red Knives"

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK was making his last camp on the Ohio, and the four weary companies of buckskin militia stretched their legs at the end of a hard day. The flame of the squad fires illumined the dark water of the river and outlined the thicket of the unknown back country, while the men drowsed before the grateful heat, sitting cross-legged. A monotone of talk broke the rustle of the wind and the lap of the water. A sentry emerged from the woods for a moment to survey the clearing and plunged out of sight.

"Jet Bonnett, dum ye, whar's thet twist of 'baccy I guv ye yeste'day?" a throaty voice called from one fire to the other. "I'm done fer a thaw, danged if I ain't, now." A milder voice answered, and the peaceful drone went on. Near the foot of the encampment some Tennessean chanted softly the Seminole corn ritual.

By the fires came a tall, lean man who stopped momentarily at each blaze to scan its circle of men. The light revealed a tanned, aristocratic face marked above all else with lines of arrogance and sullen humor which seemed to intensify with each fire the man inspected. At last, near the end of the line, he found the object of his search and broke into an impatient exclamation.

"Cheves!"

"Yes?" A figure rose to sitting posture.

"Why don't you stay by your own fire? Been trailin' you like a puppy dog. Clark wants to see you right off."

A chuckle swept the circle, and a massive-shouldered, bearded fellow gravely rebuked the messenger.

"'Pears like you ain't been doin' nawthin' but grouse this hull trip. Kind of spilin' fer fight. Ef I was Cheves, clanged if I moughtn't risk a fall with ye, Danny Parmenter."

Cheves rose and came from the fire. "Thanks," he said, walking toward the head of the camp.

Parmenter shifted his feet, cast a swift glance of anger at the bearded fellow, and hurried after his man. Striding up the roughly formed street, they appeared typical sons of the Old Dominion who in that year of 1778, during the Revolutionary War, had cast their lot in the newer country west of the Blue Ridge. Both showed lean and wiry frames beneath the buckskin, and both possessed the sensitive features and proud carriage of native Virginians. Cheves was the more solidly built. He swung along with the gliding step of an experienced woodsman, while his bronzed face, molded by hard adventure, lacked any line of petty spite.

In the darkness between fires Parmenter began to grumble again. "General sends for you pretty often! Seems like you stand mighty close to him. Policy for you to make up, eh? Sending me out to fetch you like an Indian trailer! Damn but that's fine! There's some things I can't stand in a man, Cheves, an' toadyin' is one of them! Lickspittle!"

"Wouldn't get so steamed up. Ain't to help you," Cheves drawled in response to this irritable attack.

"Don't you use that patronizin' way on me!" Parmenter turned, furious. "All I been doin' lately, seems like, is flunkyin' between you and Clark. I didn't join for that, and I won't stand it any longer." He stopped and pulled at Cheves's jacket. "Put up your fists and we'll have it out."

But Cheves broke away in a gust of impatience. "Don't be a fool! You've been an idiot ever since we left Wheeling. If Clark had sent me to look for you, I'd have done it and kept my mouth shut. Take what comes to you."

They strode on, but soon Cheves spoke again. "I don't know what you came on this expedition for...but I'm mighty tired of being ragged. I don't want any more of it. We can't get along, so just keep away from me. I'd have killed you long ago if it wasn't for a reason."

"You needn't use her for an excuse," Parmenter sneered. "I don't hide behind her skirt. I'm not afraid of you!" An incredible harshness, a vitriolic bitterness tainted his next words. "You don't win all the good things in this world. You didn't get her! She's seen through you. Hear that? She's mine...promised to me!"

"All right." Weariness filled Cheves's voice. "All right. Lower your voice, man. If she's promised you, then be satisfied. Now shut up."

The other subsided, yet for a man who had conquered a rival he seemed to lack any trace of generosity. His success appeared only to have sharpened his hatred, and he would have continued the quarrel had they not arrived at the largest fire. Around it were four men—Clark and three captains of the party, Helms, Harrod, and Bowman. Clark was broiling a chunk of deer meat over the coals while the other officers shared a faded and creased map in which they found great interest.

"Here he is," grunted Parmenter.

"You want me, sir?" asked Cheves. The discipline between men and officers in this brigade was of the rudest sort. No officer commanded, save by the downright merit within him, and no man followed unless urged by confidence and respect. The tall Virginian stood at attention only because he held a full measure of loyalty to the stern figure in front. It was a good soldier honoring a good soldier.

"All right, Parmenter. Won't need you any more." Clark nodded.

Parmenter's mouth cursed. He scowled at Cheves and flung himself away.

Clark shrugged a burly shoulder. "That lad's spoiling fast," he commented. "Here, Helms, you finish this meat for me. Sit down, Cheves."

Captain Bowman glanced toward the rear. Directly back of them the water maples and osier bunched to form a thick bit of wood, with the underbrush winding around the tree trunks. Clark caught his captain's eye and nodded.

"I know," he agreed. "Trees have ears, but this is as safe a place as we'll ever find. Hand me the map, Bowman.

"Now, Cheves, the brigade is leaving the river at this point. Can't go down the Ohio farther without some British ranger or French voyageur seein' us. Soon as they did, immediately Kaskaskia would be warned...which would ruin my surprise party. I've decided to cut straight across country from here. It's five days' march. Hope to take the enemy completely off guard.

"But capturin' Kaskaskia's only a part of the campaign. I'm plannin' other things...and I've got to know what Hamilton is doing in Detroit. Last I heard he was to bring some companies of regulars down to Vincennes as a part of the reinforcements to this country. They may be on the way now. I've got to know. And I've got to know what he plans to do this fall and winter. He's been distributing red-handled scalping knives right and left. But how many tribes has he got under his thumb? How many war parties will go out this fall? How many men are in the Detroit garrison? And are the French habitants contented or rebellious? A lot depends on that last, Cheves. And, most important, how many rangers are in the whole lake region? They stir up more danger than anybody else. You see what the job is, Cheves?" He leaned forward and tapped the Virginian's knee. "I want you to go to Detroit and find out these things."

"Yes, sir," said Cheves.

"Good!" Clark leaned back. "Now look at this map. Take a good impression of it in your mind. It's all we know of the trail between here and Detroit. This was Croghan's route in 1765 when the Kickapoos and Mascoutines carried him off to Fort Ouiatanon. It's seventy-five miles from here north to Vincennes. Two hundred and fifty to the bend of the Wabash that's by the Twigtwee villages. After that, I don't know. You'll be forced to stay off the Wabash most of the time, and you'll have to circle Vincennes and Ouiatanon. After that you'll be in Ottawa and Twigtwee country along the Maumee. Beyond these are the Pottawotomies and the Wyandotes, and they're the worst Indians on the border."

At this remark Harrod, veteran of a thousand Kentucky fights, raised his voice. "There ain't a friendly or neutral Injun the hull way," he declared. "Travel light an' fast. Don't light many fires or shoot much game."

"When you get to Detroit, play the part of an independent trader and use your head," Clark advised. "That's why I picked you. Find out what I've got to know and come right back. Pull out tonight. Tell the boys you're off on a small scouting party."

The wind threw a sudden puff of air into the clearing; the fire blazed higher and veered sidewise. At the same moment the distinct snapping of a twig came from behind them. Bowman whirled as though bitten by a snake, and the lines of his face turned suddenly savage.

"I knew it!" he ripped out.

"Maybe it's the wind," suggested Helms.

"Wind doesn't crack twigs with that sound," said Clark, shaking his head. "Stay fast, Bowman. Don't shoot. Won't do to scare up excitement now. But there's spies in this outfit! I've known it since we left Wheeling. I think that slew-nosed Sartaine is one of them."

"Wish I could ketch him at it," muttered Bowman.

"Get your outfit," continued Clark to Cheves. "Travel fast. When you return, I'll be at Kaskaskia, or I won't be alive." The slate-gray eyes caught fire, and the stubborn, long-jawed face lightened to the flare of his ambition. "Good luck!"

Cheves strode down the line of fires. Half way Parmenter intercepted him.

"What's up?" he growled.

"Nothin'," said Cheves, speaking loudly enough for the adjoining group to hear. "Just goin' on a little scoutin' trip."

Parmenter's eyes sought the other man's face and slowly the blood crept into them and his mouth curled back after the fashion of a vicious horse. "Damn you!" he breathed, "I'll not stand that!" and before Cheves could jerk away a flat palm had struck him on the cheek with a report loud enough for all men at the nearby fire to hear.

It dazed Cheves for a bit. After that, he moved forward. "I've stood plenty," he said. "You've picked a fight."

He moved into action quietly. A straight-armed jab threw Parmenter's head back, and before he could parry another blow caught him on the temple. But Cheves left an opening, and Parmenter's fist found it, leaving a crimson streak.

Both fought in silence, with their whole hearts. There was no avoiding punishment. Each tried to batter the other into submission. Parmenter's grimaced face mirrored quite plainly his purpose to injure or maim without scruple. Cheves caught him on the mouth, and he grinned through the hurt of it—grinned and seemed to slip, twisting his body, raising a knee and driving it full into his opponent's stomach. Cheves saw it barely in time, jumped sidewise like a cat, and took the blow on his hip. That trick thoroughly warmed him. A wild anger sent him forward, taking punishment unheeded and battering down Parmenter's guard weakly to his hips. With a kind of sob the latter met the final blow on the chin and slid to earth like a dummy relieved of props.

Cheves stood over him, angrier and angrier. "When will you learn to fight fair? Next time we fight, bucko, I'll kill you! I'm tired of using my fists, too. Remember that."

Parmenter raised his head, wiping away the blood, immeasurable rage in his eyes.

"All right," he answered, almost in a monotone. "I'll take that challenge. Anything goes, my friend."

Cheves turned on his heel and went the length of the clearing to get his equipment. Around the waist of his hunting shirt went the leather belt holding shot pouch, powder horn, game bag, provision pouch, and hunting knife. Last of all he picked up the long-barreled gun and his broad-brimmed hat.

"I'm off for a little cruise," he said. "Dan, you take care of the blanket. I can't pack it." He turned away from the fire and strode along the edge of the brush to the opening of a deer run. At this point he stopped to survey the clearing. Clark was busy with his venison, and the captains studied at the ancient map, but farther down the clearing a more sinister sight caught his eye. Parmenter had gone to his fire. A short compact figure slid out of the dark and gestured to him. The two met on the edge of the light and, as the second man turned, the Virginian saw him to be the slew-nosed Sartaine. Both turned from the clearing and disappeared.

Cheves squared himself and plunged through the brush. His only guides were the North Star, hanging over his right shoulder, and a mental picture of Croghan's map.

IT was Dan Fellows, wrapping Cheves's blanket around him

for extra comfort, who explained the sudden quarrel to his

companions. "Me now, I've watched them two families...Cheves and

Parmenter...since a boy. They've allus fought. Once in a while a

black 'un breaks out in the Parmenter strain. This Danny's like

that."

"You-all know 'em?" The circle paid him attention.

"Yep." The speaker crushed some leaf tobacco in his pipe and lit it with a flaring brand. "Cheves's blood is good. My folks run with them many a generation. These two young bucks always scrapped. Fought and kicked since they was knee high to a grasshopper. And always it was a case of Parmenter tryin' to git unfair advantage. There's a wild cast in his eyes.

"Lately they've fought on account of a mighty sweet girl, for the two bucks have run nip an' tuck with her judgin'. But it seems like she don't know her own mind when it comes to men, which ain't strange. Anyhow, it goes along like that until the night there's a great fight atween 'em and, at dawn next day, there was a duel. I snuck up and saw that duel from beyond some willows. Me and another Virginia man, both with guns, to see there warn't any foul play ag'in' Dick Cheves. Way to fight is ball an' ball, God helpin' the best man.

"Well, He did. There was two shots all bunched of a sudden an' Parmenter's gun dropped from his arm an' he fell. Next thing was unexpected. Cheves had turned an' was welkin' to his horse. More anybody could say Sam Bass, Parmenter had licked another little gun from his coat an' taken a fresh shot. Didn't hit Cheves, by Jo! Dick didn't even turn until he got a-horse. Then he speaks up in right smart voice like this, 'Danny,' he said, 'if it warn't for one thing, I'd sure kill you.' And then he rides on."

The circle hung on every word. Only one man of the crowd saw Parmenter and the guide slip back to their fire, gather their guns and belts and hurry again to the shadows only Fellows saw it, from the corner of his eye. Unhurried he finished the tale.

"'Twas the next day an' I was standing with Dick when he gits a note from the Ralston plantation...that was the girl's name...brought by a nigger. Dick's face just went ter black when he read it. All he said was, 'Dan, I'm goin' away.' Well, I just ketched me a horse an' here we are. 'Twas later in the trip as you boys know that Parmenter joined. Knowin' what I do, I guess none of you saw what I did. But there's one less man comin' back from this party, darn me now if he ain't."

A gust of rage roughened his voice. He drew on his belt and kicked away the blankets.

"Jed Bonnett, you keep these things," Fellows commanded—and strode, rifle a-cradle, into the shadows, following Sartaine and Parmenter over the same trail Cheves had taken a short half hour before.

IN the afternoon three days later, stubbled and sweat-smeared of face, Cheves was on the far end of his great circle around Vincennes with the broad river sparkling at him through the meshwork of the trees. The day had begun full and warm, but as the sun started down westward the heat, sullenly stifling since the Virginian had started his solitary trip, gathered into clouds. Flat and detonating claps of thunder broke in the sky, and by four or five o'clock all light was gone. A patter of rain fell on the leaves, and Cheves raised a fold of his hunting shirt to cover the powder horn.

Passing Vincennes was a nerve-tightening affair, for here were gathered the Piankeshaw Indians, and here centered the power of the British on the lower reaches of the Wabash. By rough calculation he had detoured the town at a distance of ten miles, but even at that interval the traces of scouting parties were plainly visible. He had passed five trails leading to the old settlement, and each bore the marks of recent travel.

Once at noon of the day before he had gone off trail to a thicket and was munching jerked venison when a silent file of ten Indians hurried by. Their bodies, bare to the waist, were daubed with yellow and red pigments, and from each hip was slung the belt with its burden of powder horn, shot pouch, knife, and tomahawk. Three warriors carried each a scalp dangling from the tomahawk. Cheves gritted his teeth. Those scalps meant slaughtered American backwoodsmen.

That night he forded a creek, swam a river, and camped deep in a tangle of grape vines. The patter on the leaves broke to a swift torrent, and in the darkness Cheves had difficulty in finding his way. Once a crack of brush sent him off the path, but it was only the falling of a tree. Again, the waving, sighing saplings so resembled advancing people in the darkness and drizzle that he abandoned the path for a hundred yards or more.

He took note of every forest sign, for he had learned two days ago that someone hung to his trail. In the dark of one night there had been the swish of brush, and only yesterday he had seen tracks of an Indian party doubling back around him. It looked as if a general alarm of his presence had reached Vincennes through some spy in Clark's outfit.

The rain increased its fury, and the bushes bent and twisted across the trail so that in the semi-darkness he could scarcely push his way on. The path had become a small waterway, and he was wet to the skin. But the physical discomfort didn't matter. Such a storm erased the marks of his trail and allowed him relaxed vigilance.

A curve shut off his view and some sleeping monitor, plus the cloak of the storm, let him forge ahead without reconnaissance. When he again faced the straight path, it was to find a bowed figure in buckskin rapidly advancing. The latter saw Cheves immediately and threw up his arm. The Virginian swore, but it was too late to take cover. Coming to a halt, he dropped the butt of his gun and waited.

"How," returned Cheves. He placed the man instantly as one of the many British rangers abroad in the forest who went from tribe to tribe and from fort to fort. No other man would march through the woods so carelessly.

"Hell of a day for travelin'," offered the ranger. "Where from?"

"Vincennes," Cheves answered after a rapid estimate. "So? Was there two days ago an' didn't see you."

"Just come in from Kaskaskia. In a hurry to reach Ouiatanon."

The ranger took a sudden interest, shaking the water from his dripping face. "What's up?"

"Spanish at Saint Louis tryin' to stir the Kickapoos against us. There's somethin' in the wind, and it ain't for our health."

The ranger cursed the Spanish volubly. "Never did trust any of 'em further'n I could throw a bull by the tail. I'm all for wipin' 'em off the Mississippi. Never any peace in the Illinois country till we do."

"Where you from this time?" inquired Cheves.

"Ouiatanon. Hell's a-poppin'. Couple hundred Saukee renegs broke away from their people an' won't have nothin' to do with the other Nations. Killed some Twigtwee bucks and are headin' this way now. Wouldn't be surprised if they was right on my heels." The thought made him cast a sharp glance about. "I'm on my way to get the Piankeshaws to cut 'em off. Can't have 'em buckin' British authority. Bad example. You'd better keep an eye skinned. No tellin' what they'd do to a ranger."

"How're the other Nations?"

"Fine as prime fur. Scalpin' party goes out every week from Detroit. Make it all hair, I say. Sooner we kill Americans off the better it'll be. If you're for Ouiatanon, hang to the Wabash an' the bottoms. Bone dry elsewhere. But you'd better watch for them Sauks."

Cheves picked up his gun. "Well, I've got to move. So long."

"So long. Tell Abbott I got through."

The bend separated them, and once more Cheves ploughed through the rain. He swore bitterly. It was an unfortunate meeting in the most dangerous of places. The ranger would soon enough find he had been duped, and Vincennes was but twelve miles back. Cheves was going to be vigorously pursued.

From any viewpoint his position was precarious. The storm would cover his traces for a while but, when the rain stopped, he would leave a trail that any savage in North America could follow. There was only one expedient left, and he adopted it as soon as the idea occurred. Grasping the rifle tighter, he broke into a dog trot. The water splashed over his head, but it made him only a little more miserably cold.

On and on he ran, slipping and sliding, picking a way where the brush had fallen across the path, gaining speed where drier ground permitted it. The gray light faded before a tempestuous night; the way grew less and less discernible and finally was altogether blotted out. The dog trot slowed to a snail's pace. The trail was worse than anything Cheves had ever experienced. The wind howled savagely, and the rain poured down until the trace became a torrent, and he no longer could pick his direction. It was utterly black. Time seemed remote. A thousand demons howled, and the bitter cold cut through to the bone. In such a state he fought his way on until the expense of energy was greater than the progress made. At that point he turned into deeper brush and, hollowing out a rest among the vines, crouched down and spent the night.

At break of day he was up and on again. He had gained during the night, he knew, but would lose by day, for the Piankeshaws could trace him by a hundred short cuts with the common adeptness of all woodland tribes. Toward noon the wind fell off, and the rain abated. By mid-afternoon the sun forced its way through the dreary clouds, and shortly the earth was a vast rising mass of steam. To Cheves it was a great comfort, drying and warming his soaked body, but with that comfort came a new necessity. He must leave the trail and seek the forest where his footprints would not be so plainly revealed.

He was on the point of turning off when, from directly ahead of him, there came rolling through the forest the report of a gun, followed by a series of short, bouncing crashes. Cheves drew up, nerves on edge. It sounded like a hunter—possibly from Vincennes. But no, a hunter from the Fort would have small necessity of traveling so far afield for game. Perhaps, then, it was some independent British trapper.

The Virginian was about to step into the brush when a stir from behind whirled him about. He stopped, half turned. Twenty yards away stood a half-naked, paint-daubed Indian buck. Out of the corner of his eye Cheves saw another advance from the brush in front. He was trapped! For a moment the idea of resistance surged over him. A step and a shot and he would have at least one of them. But the idea passed swiftly. That rifle report meant a larger party nearby. He lowered his gun and threw up a hand in token of peace.

The Indians closed in, rifles advanced. The foremost one uttered a monosyllable grunt and jerked away the Virginian's rifle. He was given a push and turned down the trail. Thus marching, they went through an open glade, turned off the trail to deeper forest and, after ten minutes' weaving, came to a clearing of some eighty or more yards across.

In the center were several small fires around which were gathered a war party numbering fifty or sixty young braves.

Cheves was shoved into the middle of the encampment toward an Indian who, by physical fitness and bearing, seemed to be the chief. He was fully three inches taller than any other man in the clearing save Cheves. His chest was broad and deep, and his face carried the bitter lines of discontent which only accentuated his authoritative bearing. He heard the speech of his scout, nodded his head, and suddenly sprang forward with a savage gesture. "Breetish?" he demanded.

Instantly it came to Cheves that these were not Piankeshaws. This party was a detachment of the renegade Saukee people. So, in commingled relief and consternation, he simulated a deep disgust, wrinkling his nose.

"No...no!" He switched to French which once had been the universal tongue of the forest: "Je suis americain." The chief was puzzled. "Eh?" he grunted.

Cheves tried another word, one commonly used to describe Americans around the Ohio and Mississippi villages. "Not British. I Bostonnais."

The circle around him moved in recognition of the word and broke into voluble conversation. Then the chief made another of his swift moves, thrusting forward his hand and ripping back the Virginian's hunting shirt. Beyond the tanned V was white skin. The chief ran his thumb over it, shuffled his fingers through Cheves's black hair, stared at his eyes, tweaked his nose, and finally fell to examining his apparel with minutest scrutiny. His fingers tested everything before he muttered something that sounded to the Virginian like acceptance. "Bostonnais," he grunted, and the circle dubiously nodded.

At that moment a scout ran into the glade and threw out a guttural warning. The men about the central fire sprang up. There ensued a rapid parley, with the scout swinging his arms in a wide circle toward Vincennes. Another scout ran in from a different angle and made a quick report. Cheves, watching closely, saw some new turn of event had disturbed the Indians. The tall chief chanted a brief word, and the clearing became animated. The scouts slipped back into the brush. Even as the Virginian wondered, the main body shuffled into single file, with himself among them, and went quietly down to the overgrown trace. There they followed it, away from Vincennes.

Away from Vincennes was toward Detroit! Cheves relaxed. Their destination he did not know, but any destination to the north meant the closer approach of his own goal. So, for the time being, he could float with the tide, secure from ambush. When the Saukee trail forked away from Detroit, then must he commit himself to a different policy. Not before.

All night they traveled as if sorely pressed by an enemy to the rear. Cheves decided the ranger he had met had succeeded in calling out the Piankeshaws in such large numbers as to repulse the Sauks. Once in the small hours a ripple of warning passed down the file, and it halted off the trail for a moment. They resumed march in complete silence, each man slipping forward as the figure ahead dropped out of sight. There was nothing to disturb the swift shuffle of moccasined feet save the rhythmic breathing of Cheves's immediate neighbors.

At daybreak they camped in another secluded grove and Cheves, dead tired from forty-eight hours of constant travel, fell to a troubled sleep that seemed to last only a moment. Again they were up and on.

There was, Cheves saw, an undercurrent of uneasiness in the column. Scouts went off on the dog trot and came rushing back later with brief reports, to go off again on the run. Thus far the trail had led away from the Wabash, but the new day's march had only been started when the party, apparently because of news brought by a scout, slanted northwesterly, gaining the stream again. At the same time the pace quickened, and Cheves's aching muscles cried for relief. But he dared not falter. In such a situation a white man's scalp was much easier to carry than his body.

They reached the Wabash at noon, plunged across, rifles held arm high, and climbed the farther bank. Topping the ridge, Cheves saw a long undulating plain, smiling under the afternoon sun, luxuriant in vines and hemp grass. The forest was behind; they were entering a new country with a new dress. Ahead was the suggestion of the Illinois River blending with the indefinite mists of the distance, and at that moment Cheves knew they were turning away from the road to Detroit.

Set as he was on this definite goal, the turn of fortune gave him a bitter taste of defeat. It had never been in his nature to accept defeat calmly and now, lightning quick, his thoughts turned to escape. But the Indians were already far beyond the river, crossing the hot flat land, and there was no possible avenue by which he might get clear in daylight. The nearest route to safety was through a thousand yards of open country exposed to fifty rifles. When night came, he might break away and run back for the river, but not before. So he accustomed himself to the swifter pace and said nothing.

The uneasiness seemed to grow stronger. Cheves could feel it in the braves about him and, when night came and they camped in a small copse, an increased number of scouts and sentries was sent out. No fires were lit, and a somber silence sat upon every coppered face. Cheves shared the sense of impending trouble. It was nothing definite, but rather an aura caught from these nomadic men who read their destiny in the leaves and smelled it in each puff of the wind. Some disturbing sign had warned them, and now they were straining every muscle to reach a secure haven.

With this foreboding Cheves dropped to a fitful slumber in the protection of a thicket, waking from time to time as warriors arrived and departed. On each waking it seemed the tension had increased and that he was the sole sleeper. He did not know at what hour of the night a rough word brought him up. His guide slipped by the trees, coming to a deeper tangle of the brush, and here stopped. Cheves dropped a hand to his belt and felt for his hunting knife. All about he saw the darker shadows of the Sauks, seeming in station for a definite attack.

Though he was prepared for this attack, the fierce, sudden gust of rifle fire surprised him. In a general way he thought the storm would break from northeastward, but the attackers were cleverer than that. So quietly as to be without opposition they had encircled the wood and now poured fire from all sides. The leaves pattered and brushed as from a heavy rain. Cheves, unarmed, threw himself flat on the ground. There was no safer place in that doomed wood, and the Virginian knew it to be doomed after the first volley. For, from the sound, fully five hundred rifles were speaking. It seemed only a matter of time before the renegades were annihilated, and Cheves took thought of his own chance to escape. Presently his guide, finding himself too deep in the thicket to be of any aid, left Cheves and crawled toward the firing. It was the last Cheves saw of him, or of any of the Sauks, alive.

The engagement settled to a stubborn rattle and patter of shots, with the occasional war cry catching and going around the attacking ranks. There was no answer. The renegades preserved grim silence, doing damage while they could. For a half hour it continued this way, dying down, flaring up, and at last settling to a deceptive calm. It seemed to Cheves as if all the fighters were holding their breath, waiting for the last act of a bloody drama.

It came presently, heralded by a full concerted war-whoop from five hundred throats, a lusty baying, a throaty snarl, a feverish yelping, which turned the Virginian's blood to ice. Then the attack closed in, rifles cracking.

The Virginian could mark each successive advance, could hear, almost, each individual battle, so strategically located was he. As the assault beat back the first line of defense, the ring narrowed and its edge came nearer to the covert where he rested. The last defiant cry of the defeated going down before knife or club, the last death rattle, the grunts and labored breathings of hand-to-hand conflicts—all mingled to form the welter of massacre.

No sound of mercy was given or of pity asked. Grim and stark and relentless. And above all this the Virginian heard, of a sudden, commands in a broad Celtic brogue.

"At 'em, me pretties! No mercy for the renegs! Bring me back sixty scalps! Hunt 'em down and stemp 'em out! I want topknots! No more renegs in this territory! Rum an' wampum, boys! Oh, ye red, murtherin' divvils, grind 'em out an' bring me the hair!"

IT was so unexpected! One moment the entire woods reverberated with sounds of death, with the gurgle and snarl of human throats uttering exclamations of anger and fear, with blows given and blows taken, with the noise of a surging, vindictive advance toward the heart of the brush. So furious was it that the Virginian had given up hope, resolving only to account well for himself in the last mortal struggle. Then it was all changed. The raucous, commanding voice of the Irishman was the respite of a sure death sentence.

"After 'em, my children! No prisoners! Bring in the hair! Go on through the woods! Get every mother's son!"

He came directly toward the covert, a heavy, aggressive body knocking the brush aside, fighting, swearing furious black oaths, and chanting the shibboleth of frontier war: "No prisoners! Bring in the hair!"

Cheves crouched, ready to spring. The last bush parted and the dark figure bulked dimly to view.

"Any of them damn' renegs here'?" he bellowed.

The Virginian, slightly to the rear of the Irishman, catapulted forward, pinioned his victim by the arms and threw him to earth. They rolled over and over, the surprised man heaving and kicking. His rifle fell aside.

"Shut up," breathed Cheves. "I'm a ranger...got caught by these Saukees. Easy, easy! Call off your dogs!"

"Holy mither, ye were onexpected!" exploded the Irishman. "Walked right into your arms, I did. I'm a blind fool! If 'twere an Injun, my top piece would be airin' now." The thought of his position enraged him. "All right, man, ye needn't hang on so tight. Leggo, or I'll be forced to gouge." Cheves laughed and released his grip. The Irishman got up, still swearing. "A damn' oncivilized way o' shtoppin' a man! Who might ye be an' whare did ye get them gorilla arms?"

"Ben Carstairs, Kaskaskia. Who are you?"

"Jim Girty," growled the Irishman.

The fighting had died out. Now and again a rifle shot or war- whoop reached the two, but the skirmish was practically over. Already fires were burning on the plain and the Indians, cooling from the fever of killing, numbered their slain and counted scalps.

"Well," said Girty, "let's get out of this. Stay by me while I set 'em right. It's a ticklish business when Injuns are in heat. I was too damned careless! If it had been a Saukee, now!"

They passed into the clearing together, and Girty threw out a guttural word here and there. Cheves found himself the focus of glittering, blood-shot eyes but with his companion felt reasonably safe. What interested him most was the Irishman's stature. He was a short man with barrel-like shoulders, jet black hair, and a beard which seemed to cover every exposed bit of skin. Above it were mournful, suspicious eyes which, like those of the Sauk renegade chief, sought every detail of Cheves's apparel.

"Ye're a long, lean scantlin' of a man," he grumbled, "but I take off my cap to those arms. Now what's your story?" Cheves sat by the fire and told the same tale he had invented for the ranger near Vincennes. Its effect was much the same.

Girty slapped a legging and cursed fluently in three tongues. "Those hellish Spaniards! Never saw a good 'un, an' never expect to. I've told Hamilton many a time he should go south an' wipe 'em out. By an' by there'll be hell a-poppin' an' more dirty work for the likes of you an' me. Arragh! Hamilton's weak-kneed, and he don't use his head. What sort of man is that?"

The Indians gathered about the huge central fire on the plain and were uttering a low rhythmic chant which ebbed and flowed in celebration of victory. Girty swayed with the chant.

"What sort of man is that?" he repeated. "It's dog eat dog out here. Many a time my scalp's teetered because some Tennessean cuddled his rifle too close. Raise hell with 'em, I say. When I plug one, I say: 'Girty, that adds another day to your life.' Darn me if I don't."

"Why worry?" asked Cheves. "We've got things sewed tight. Although I do hear there's Shawnees near the falls waverin'."

Girty turned his head and looked fully at Cheves, the black eyes dilating like those of a cat. "Ye talk mighty like a Virginian. I've heard that drawl afore."

"Man, you would, too, if you lived in Southern country."

"How come ye be a British agent, then?"

"A man's politics, Girty, don't always bear looking into."

Girth nodded. Yet like an animal who has smelled the taint in the wind he could not be immediately quieted. "Whare's your papers if you're from Kaskaskia? Rocheblave'd be sendin' some on to Detroit."

"Saukees got 'em and put 'em in the fire. It's all in my head."

Again Girty nodded. "Well, ye may be right," he admitted. "I've no cause to pick at a man's politics. Maybe I'm over shy. Niver met a man I'd trust save me brother, Simon. The trail does that."

The dance of victory was over, with a final shout and leap and insult at the Saukee gods.

"'Tis a hard tomorrow and I think I'll sleep," said Girty. "We're goin' on to Weetanon where there'll be a party for Detroit." He fell asleep almost instantly.

Cheves remained awake longer, thinking over his next move. Clark had advised him to assume the role of independent trader but that had not seemed to promise as much information as he could pick up while masquerading as a British ranger. If he should meet anybody from Kaskaskia in Detroit, he could clear himself by posing as a new arrival in the Northwest, having come by the way of the Ohio, or he might say he was a special agent through from Tennessee, or that he had made a long circle at the behest of Haldimand, Lieutenant Governor of Canada. By these means he could gain inside councils. It meant a far more dangerous role, and it demanded swifter action. Already the ranger he had met near Vincennes constituted an awkward obstacle. He must get his information quickly and pull out. With that decision he fell asleep, utterly exhausted.

They were on the trail again in the gray of morning, pushing northeastward. Midnight brought them to Ouiatanon. Girty, impatient and overbearing, found the Detroit party gone on. He tore around the stockade like a madman, roaring curses.

Girty and Cheves slept that night in a far part of the fort and, relieved of watchfulness, they slept deep, not hearing the quiet entry of another party. Before daylight Girty was up, growling at Cheves that it was time to be on their way.

The newcomers were stretched on the hard ground of the court. Cheves, looking at them, saw only the blur of a white face raise up and turn toward him. No word was said. The man dropped back to his blanket again. Cheves followed Girty beyond the fort wall. The sentry banged shut the door and thrust home the bolt. On trail once again.

Thus far did Cheves and Parmenter miss each other at Ouiatanon, for it was the latter who had raised and stared, unknowingly, at the two men passing out of the fort not ten feet from him.

Up the long narrowing bend of the Wabash Girty hurried, following the river as it slanted eastward. Two days' march brought the rangers to the main column in the Twigtwee country. It was rougher going now, but the lure of the capital drew them on and instilled tired legs with renewed vigor. They crossed the Maumee portage, borrowed Pottawatomie canoes, and floated down the river to the lake. Fifty miles across open water brought them within sight of the gray, heavy palisades of Detroit town.

THE canoes brought up at the King's Wharf, a structure built of heavy logs split in half and covered by planking adzed smooth. Gray and weather worn, it stood solidly in the river. For nearly eighty years it had seen the departure of the fur brigades into the North and had witnessed them come sweeping back, singing their lusty free songs of river and wine, with the gunwales of their craft slipping low to the weight of hundreds of bales of priceless fur gathered west and north of Michillimackinac. The party ascended the embankment, went through the huge timbered door, and were within the town.

Detroit had started with a small stockade by the river. Each additional house and each additional alley stretched the walls until now the town inside the palisades contained about sixty houses and more than two thousand people, mostly French-Canadian. Outside the palisades the Frenchmen had long, narrow farms extending back from the river. It was natural that Detroit should start with a large water frontage and taper as it proceeded toward the forest, with the houses giving way to a large parade ground beyond which was the fort. There was scant regularity to the crooked alleys. The palisades could be entered by gates at the east and west and also at the two wharfs, King's and Merchants'.

Girty led the party single-file through the alleys. Small, low-hanging houses made of logs and rough board fronted the street. Cheves caught sight of piled counters and shelves, while at intervals the proprietors came to the doors and threw effusive greetings at him. They passed a wine shop, and Girty suppressed a bolt.

"You keep them whistles dry ontil we reach the fort!" he growled.

Winding and twisting, they crossed the parade ground worn hard by many tramping feet and arrived at the fort gate. The fort formed a part of the town wall, yet was itself palisaded from Detroit by a bastioned barrier. A sentry challenged the party.

"Hell, I'm Jim Girty!" answered the agent. Restraint of any kind angered him. "Party from Weetanon. Put down that stabber an' let us by!"

They passed into the yard, flanked by officers' quarters, barracks, and general store rooms. Girty seemed to know his way, striding across the square and through a doorway where Cheves, entering, found himself in a guard room. A lieutenant rose as they entered.

"Girty. You're back early. What luck?"

"Found 'em and took hair," the agent reported, drawing a significant hand across his neck.

The officer slapped the table. "Good! The governor will want to hear that right off." Girty nodded. The officer turned to Cheves. "Don't believe I know you," he said, a professional mask dropping across his face.

"Carstairs is my name," said Cheves, "from Kaskaskia."

"Lieutenant Eltinge," explained Girty to the Virginian. The two shook hands.

"From Kaskaskia?" Interest thawed the lieutenant. "Been looking for word from there for more than six months. Place might have been sacked for all we know. What's up?"

No news from Kaskaskia for a half year! The talkative young subaltern had unwittingly taken a great load from the Virginian's mind. He was safe until dispatches did arrive from that distant outpost.

"Bad news," he returned. "I had dispatches."

"Saukees got him," interrupted Girty. "Was headin' him straight for the Illinoy when I come up." He grew restless. "Go in and tell the governor we're here, will you?"

The lieutenant, checked in his gossip, rose with reluctance and disappeared through the door.

"He's harmless," said Girty, ranging the small room. "Not snobbish like most of 'em. Got a lot of book learnin', I hear. Hell of a lot of good it's doin' him here!"

Cheves was preoccupied with the coming interview. Luck had played with him so far, save in one instance. The thing that would most establish his position was the corroborative testimony of Girty, a trusted agent. And Girty had a good tale to report. He had pumped and cross-questioned the Virginian all along the Maumee River until finally he confessed himself satisfied.

"It sounded fishy at first," he told Cheves. "I know most rangers hereabouts, that's what got me. Can't take anybody on their face. If I'd been convinced you was Virginian, you wouldn't ha' lived five minutes." And the Irishman's sullen eyes flashed with a diabolical humor.

The masquerading had been far easier than Cheves had dared to expect. Too easy, he thought.

Eltinge came out. "Go right in," he directed, holding open the door. "Governor's very anxious to see you both. Mind stopping on your way out, Carstairs, for a little chat? Been trying to get down to that country on brigade for a year."

Cheves assented and passed down a dark corridor. At places store rooms broke the hallway like bayous in a creek, and they opened and closed three different doors before coming to the entrance of the governor's office. Girty strode boldly through.

"Back again," he announced gruffly.

The very contrast of the place astounded Cheves, unused as he was to seeing luxury in any western building. Coming from undressed timber and split puncheons, he now stood in what was undoubtedly the finest, most pretentious room in the west country. The stained walls were covered with furs and an incalculable array of Indian blankets, beadwork, and weapons. Immense polar and grizzly bear hides covered the floor. Around two walls ran a shelf of books four tiers high. A couch held place in one corner, draped by a silver fox robe. In the center stood a mahogany desk, from behind which the governor had but recently risen.

As for Hamilton, Cheves found him to be one of those indeterminate persons who seem never to possess a striking characteristic by which they may be remembered. Medium in build, tending to corpulence, no great amount of expression on his face in repose, but showing traces of latent nervous excitability, hair graying, possessing an English shopkeeper's features—he seemed, of all men, to be the least fit for governing his wild dominion and the least capable of carrying out a ruthless frontier war. And yet he was doing just that. He was the man whose name spelled anathema to every border settler.

"Glad to see you, Girty," he said in a short, hurried voice.

Cheves introduced himself. Girty broke through formalities in his restless way and delivered his news. Hamilton's eyes lit with animation.

"You got them all, Girty? Good...very, very good! Now we sha'n't be bothered by insurrection for a while. It must have been an affair."

"'Twas!" replied the ranger in a sudden flash of pride. "Wish to God you'd do the same with the Americans. Saw half a dozen prisoners in the yard. Prisoners ain't no good. Use the knife. That'll make 'em cringe!"

The governor's face set with determination. "You can't scalp a helpless man, Girty."

"Better if you did," growled the agent.

"Damn it, man!" exploded Hamilton. "I won't have my hands dipped outright in blood. The world calls me murderer as it is. Understand?" He saw dissent in the ranger's face and turned impatiently to Cheves. "Now, sir, tell me of Kaskaskia. Where are you from? I haven't met you before."

"From my Lord Carleton. I had some documents for you, but the Saukees got them."

"Carleton...Carleton! What has he to do with you?"

"I came by way of New York, toured the Pennsylvania country, got to Fort Pitt and enlisted in a flat-boat company down the Ohio as far as the falls. From there I went to the Holston country. Strayed into Saint Louis as an independent trader and then made my way to Kaskaskia," Cheves explained.

"What's the news from east of the mountains? I never hear a thing. No dispatches from New York for a month."

"The rebel, Washington, has reached the end of his tether."

"Ah, they grow weak!" Hamilton exulted. "Now Kaskaskia?"

Cheves unfolded his perfected tale of intrigue and plot—of Spanish designs, of a thousand details which kept the governor on the edge of his chair. Cheves played the man for double purposes. Above all he must get the governor's confidence and secure an exchange of vital news. What were Hamilton's designs on the far southern corner of the Illinois triangle? What schemes were they harboring against Ohio and the Pennsylvania frontier? Of late there had been whispers of a great Indian uprising. What truth to it? And above all things—what of Detroit's vulnerability? So Cheves spread his web of words. He cherished the wild plan of working Hamilton to a state where a detachment of troops might be sent down to Kaskaskia from Detroit, thus weakening the main garrison. He, Cheves, would go along, run ahead to warn Clark, and ambush them. Detroit would be wide open then.

When he had finished, Hamilton leaned back and closed his eyes. For a long period he seemed to be thinking. Of a sudden he startled Cheves by observing: "Carstairs, you sound like a Virginian."

Cheves forced a smile and turned to Girty.

"Your same suspicion," he said and was further alarmed to see the sudden hardening, the sudden freshening of suspicion, in the ranger's sullen face.

"Damned if I didn't think so, Governor. But he's got a good yarn."

"It's nothing, perhaps," said the governor. "That's all, Carstairs. Stay in the fort until I get my correspondence ready for return. Girty, I've got something for you."

Cheves acknowledged the dismissal and went down the hall. He would have given much to have overheard the rest of Hamilton's talk to Girty. At the door he found Eltinge shuffling disinterestedly through a book. He dropped it quickly.

"Ah, back to chat with me," the British officer welcomed. "Have a real Virginian cigar. Pretty rare nowadays. I've a friend who smuggles them through. Let's take a turn about the yard."

The smoke was a luxury and Cheves said so.

"I'll get you a handful after a bit," rejoined Eltinge. "Wanted to talk with you. Minute I heard your voice I spotted another University man. I think I'm the only Oxford chap west of Montreal. I get very tired hearing jargon. What's your school?"

"William and Mary's," answered Cheves truthfully. It was a ticklish business, this mixing of truth and fiction, but it served his purpose, and he saw by Eltinge's face that he had established another contact within the circle he most needed to move during the next few days.

Eltinge launched a storm of questions, and Cheves began a description of the Ohio country which lasted for many turns about the yard. A bugle call brought the stroll to a halt.

"First mess call," said Eltinge. "Come to my quarters and we'll clean up. You're my guest at officers' table tonight. Anybody arranged to bunk you. No? I'll attend to it."

A second call drew them to an inner part of the fort where Cheves was admitted to a low, heavily raftered room lit by innumerable candles. A blazing fireplace dominated the scene, and in the center of the chamber was a long table around which some ten officers were gathered. Eltinge directed Cheves to a seat.

"Gentlemen, Mister Carstairs, on the King's business from Kaskaskia," he announced.

After that the Virginian found himself busy detailing his tour for the officers' entertainment. When the meal was over, he left the hall and returned to the open court.

"I believe I'll take a swing around the town," he told Eltinge. "It looks interesting."

"Would go along were I not on guard," Eltinge replied. "But be a little careful. We don't have entire harmony in Detroit. Too many French-Canadians...and there's a small group of American sympathizers we can't lay our fingers on. Three weeks ago a ranger who'd just come in from Little Miames disappeared, and we never did find him. So watch the dark alleys."

The Virginian strolled through the main gate as the late twilight faded into dark. Winking lights gleamed across the parade ground over which he walked, gradually approaching the mouth of a narrow alley. Somewhere a bell tinkled, sounding clear and full in the quiet evening air. To Cheves it was blessed relaxation after the weary travel. Here for a brief time he might loiter.

The alley enveloped him with its darker shadows. Once he flattened against the wall to permit a horse and cart to pass. The driver, probably late in his return home, urged the weary animal forward with unwonted grunts. The outfit creaked and clattered into the night. Cheves went on and came to an intersection, then drifted aimlessly to a new alley, absorbing the sounds and sights and vagrant smells of this far-famed western capital. Sounds of violins came from many houses. Windows of dressed oilskins drawn taut over frames let out yellow shafts of dim light. The door of a wine shop opened suddenly in the street and Cheves walked in, seating himself at a vacant table. The low-ceilinged room was filled with smoke and the babble of many men. A buxom girl of twenty or so came up for his order.

"Wat you 'ave?"

"A glass of port," returned Cheves.

He was aware of being keenly inspected by the men of the place. A natural thing, he decided, for here were typical Frenchmen, while he was labeled from head to foot an Anglo-Saxon. Well, let them inspect. He did not care. Perfect serenity pervaded him this one evening. Surely he could drop his guard for a short time.

He did not see four men slip quietly from the door, for his eyes were fixed on the glint of light through the dull red color of his wine. It was excellent port and felt tremendously good on the flat of his tongue. After the second glass he paid his bill and walked out.

At first it was utterly dark and he stood in the middle of the street, arms slightly forward for protection, while his eyes became accustomed to the night. His ears, always sharp and attentive, caught a scraping of feet nearby. For a moment he thought of Eltinge's warning, but his guard was relaxed and he could not bring himself to realize danger. He groped forward.

It was absolutely dark. Only the faint lights through the oilskin windows guided him. The alleys gave way to another intersection, broader and lighter. He paused, deciding to return to the fort. It was useless to grope through the town. He would see it under the better light of day. Turning, he reentered the alley.

Behind the wine shop he heard the scraping of feet for a second time, now closer by. He could not disregard this, and instinct threw him against a wall. Two shadowed figures advanced through the blackness and stopped before him. Cheves could not distinguish their faces.

"Pardon, m'sieur, but is it that you know the way to King's Wharf?" one of the men requested. "We 'ave just come in by bateaux. Thees town is strange."

"I think it's down this alley," returned Cheves.

He turned unsuspectingly to point the way. It was a fatal move. In some manner two men had slipped along the wall behind him. When he turned, they were upon him. A club came down on his head with the force of a ton of lead. A streak of pain and red light shot through his brain. Falling forward, he had this last thought, too late to help him: Ambushed again! Oblivion closed over him.

THE awakening of Cheves was by far the most painful event of his life. A thumping headache was his memento of the attack, and his whole body caught up and repeated the throb. A musty smell filled his nostrils, and he seemed to be tossing back and forth in space. He tried to wet his lips and then was aware of being gagged. As his senses flooded back, he determined to rip off that impediment but, when he moved his arms, he found them trussed to his body. A kick of the feet revealed them likewise bound.

"Ehu, ehu," came a tobacco-cracked voice. Nom du nom, allez.

The grunt of the cartwheels, the grumble of the driver—and he, Richard Cheves, bound on some unknown journey beneath a pile of straw. The cart hit a rut and climbed out with a jar; the pain became too great, and the Virginian dropped away to a far land, hearing the stentorian cry of a sentry:

"Halt there!"

The next thing he experienced was the teetering of the cart on a dirt road and the plock, plock of the horse's feet. A fresher air filtered through the straw and his head felt immeasurably better. If he might only relieve his chafed wrists of the rope and his cramped mouth of the gag...

"Get on, François, prod that beast! We can't be all night on the road!" a second man said.

"Eh? W'at you t'ink dat horse can do?" responded the gruff voice. Cheves recognized it now as belonging to the same man who had passed him in the cart earlier that night. "He ees no race horse. Wat you t'ink?"

"I know, I know. But prod him along." The second voice was that of an Anglo-Saxon; Cheves could not be mistaken about that. "We've got to get under cover before some sort of general alarm goes out."

"By gar, dat's right," assented a third voice. "Dat sentry, he look ver' close on us w'en we pass by dis time. I t'ink mebbe he got suspicions of men w'at travel by de night time. Speak to dat animal, François."

Thus encouraged, the driver lustily cursed the horse in fluent Gallic patois, using tongue, hands, and feet to express his purpose. The animal must have long been acclimated to its driver, for Cheves could feel no appreciable difference in the gait. At last the old man grew angry, and the Virginian heard him climb off the vehicle, run ahead in his clumsy sabots, and strike the horse on the withers. The cart gave a quick jump forward.

"That's it, François. Prod him along. Work that animal more and give him less oats. He's overfed and lazy."

It was becoming insufferable on the bottom of the awkward contrivance. Cheves could endure it no longer and, summoning the whole of his energy, he gave a desperate heave and raised up. The hay cascaded about him, and the blessed star-spangled sky broke clearly overhead. Simultaneously the two men remaining on the cart turned about.

"Hah, de fish he 'ave flopped," observed the younger Frenchman. His face broke into a sardonic grin.

Cheves was not so much interested in him as in the other man, a young, clean-cut fellow evidently not over twenty-five, dressed in homespun which fit snugly over a compact, muscular frame. His not unhandsome face, plainly visible in the clear starlit night, surveyed Cheves with a somber noncommittal gaze.

"You have a heavy clout, Pierre," he observed. "More than you needed to!"

"Bah!" said the younger Frenchman in disgust. "Dees Engleesh 'ave ver' strong heads. No t'ing can bodder dem. Eet was just a lettle tap d'amour."

"We're not midnight assassins," the leader frowned, surveying the Virginian's face carefully. "You look dashed uncomfortable there, my friend. Also you appear to have some kind of intelligence. Most British rangers don't," he continued. "Now, if I take off that gag, will you promise to keep your mouth shut. On your honor?"

Cheves nodded vigorously.

"No!" said Pierre. "Don't take no trust in any of dem killers!"

"I have your promise?" persisted the other man.

Cheves again nodded his head. Pierre gave a sigh of disapproval and turned away. His partner moved forward and relieved the Virginian with a few deft turns of the bandanna. The latter could not have said a word at that moment if he had so desired. His jaw muscles were half paralyzed. Carefully he twisted his mouth to lessen the pain, wetting bruised lips and tentatively biting them lightly to massage back the blood.

"Better, isn't it?" asked the man in homespun.

Cheves nodded, essaying a half inaudible, "Thanks."

The road they were following kept close to the river, winding through sandy fields and many orchards. Whitewashed houses and barns showed in the distance along the route, resembling so many sheeted ghosts marching across the countryside. A mile or more behind the cart Cheves made out the palisades of Detroit. Suddenly the horse turned off the main river road and went along a ruttier, less traveled way.

"You'll have to lie down," was the curt order.

Cheves obeyed promptly. He had no mind to be obstinate now; it was futile, and moreover he had given his word. For another quarter hour he watched the sky, while the cart jostled and bumped through an unusually large orchard. The outlines of a barn showed over the sideboards, and finally the elderly Frenchman trudging by his horse gave a brief grunt. The cart stopped; the men dismounted, and Cheves waited the next move.

A few whispered words reached him; the head of the cart dropped as the horse was unhitched and led away. Pierre crawled over the sideboard and cut the rope with a swift slash.

"Climb out, m'sieur, but don' try to run off," he directed. A long-barreled, unwieldy pistol appeared from beneath his coat.

It required some effort for the Virginian to reach the ground. He stamped his legs and swung his long-fettered arms to restore circulation. The exercise set his head to throbbing more painfully, and he desisted. Running a hand over his face and head, he was surprised to find the amount of blood caked there. The blunt weapon had cut the scalp badly, and the furrow lay open to the touch of his finger. A gust of anger swept him, and he turned to Pierre.

"I'd like to have an even break with you some time with my fists, my friend," he said. "I think I'd pay you back for this."

A sardonic grin was the reply. "Any time, m'sieur," the Frenchman promised.

"That's enough of that," the leader of the party cut in. "Shut up, Pierre. As for you, Mister British Ranger, you're devilish lucky to get off with a plain blow." For the first time Cheves heard heat and bitterness creep into the voice. "Your cursed cut- throat Indians use scalping knives. I guess you shouldn't be bellyachin' over a little tap. All right, bring him along, Pierre."

An orderly pathway bordered by whitewashed stones led from the barn to a house sitting amidst a grove of trees. They came by this house, went to the rear, and opened a trap door to the cellar.

"Step down," Cheves was invited. "At the foot of the steps you'll find yourself between two bins. Go straight ahead ten paces or so and there'll be a roll of tarpaulin. That'll be your bed for the night, Mister British Ranger. I wouldn't bother about looking for ways to get out. There's no windows and only two doors. The one up to the kitchen is locked. This one will be also. I suspect that Pierre or François will be nearby most of the night. Both are good shots."

Cheves accepted the situation without a word of protest. Throughout his whole life he had pursued one plan of action: be a good Indian until the breaks of luck came. If none came, then there would still be plenty of time left for desperate action. He had emerged victorious from many a straitened and grim situation by this method. Just now his muscles hardly obeyed his will, and in his enfeebled condition he eagerly embraced the opportunity for rest. Slowly he descended, bending his head to pass the sill. The doors closed over him and a hasp fell audibly on a staple lock. It was pitch dark.

Following directions, he crept along a dirt floor, hands touching parallel bins. He found an apple in one and took it. Farther on, his foot struck the tarpaulin and he knelt down to smooth out a fold of the stiff, tar-scented fabric, making a rough bed. Into this he crept, and dragged a lap of it over him as best he could, munching the apple. Finally he fell into a fitful sleep, miserable and cold, and with this one thought haunting him: his pursuers were doubtless nearing the city. The messenger from Kaskaskia might come in at any moment—and here he shook and shivered in a dank cellar while his chances in Detroit grew thinner and more desperate.

HE did not see dawn come, but the shuffling of feet overhead heralded breakfast and the new day. After a while heavier steps tramped across the floor; a scraping of chairs and feet ensued. It all whetted the Virginian's appetite and made him sorely conscious of his hurts. Yet, for all the buffeting he'd received, he found himself clear of head and lacking only some kind of food to be stout and fit for service. He rose and groped to the apple bin. Apples helped, but it was hot tea he needed to thaw out the cramped muscles.

A trap door opened from above. "Come up," a voice commanded.

A shaft of yellow candle light revealed the way. He got through and stood in the kitchen. The two Frenchmen of the night before were there and in addition a buxom mulatto presided over the kettles hung on the hearth.

Pierre held the same clumsy pistol. With it he motioned toward the kitchen table, where Cheves sat down without a word and ate what came before him. The meal performed wonders for him, restoring his strength and refurbishing his self respect. This latter quality had fluttered low in the night. Now again he could wait with smiling confidence for his turn in the swift, uncertain passage of events. Meanwhile he had figured out for himself one puzzle. These Frenchmen were probably servants of the young leaders—not servants in the usual sense, however, inasmuch as the man had allowed them considerable freedom of speech. A closer bond of interest held them together, and that bond, Cheves guessed, was a common hatred of the British. Well, they had gone to a lot of trouble and hazarded their lives to kidnap a Virginian who wanted nothing so much as to be back inside the walls where he might do some good to their common cause.

But did he dare tell of his true identity? A thousand prying ears might overhear and carry the news to town. There might be counter spies. Would they believe him? He doubted it.

He drank the last of the third hot cup of tea and leaned back. That was a signal for François, who had watched him like a cat, to disappear through a door. Presently he returned and directed at Cheves the single word: "Come!"

The Virginian followed with alacrity, for he hoped now that he might get to the core of this mystery. A hallway opened into a large, well-furnished living room. The breakfast table had been recently abandoned and drawn aside, the dishes still on it, while two men sat before a fireplace and smoked morning pipes. Cheves, giving first a casual glance to the younger, knew him as the leader of the previous night. Then he turned his eyes to the elder and received a great shock.

The man had risen and stood supporting his spare, bent frame on the back of a chair. His white unpowdered hair, his blue-gray eyes, his thin aquiline nose, his whole proud, redoubtable carriage—Cheves recognized them all in one astonished wave of joy and relief.

"Colonel Ralston!" he exclaimed.

"Richard Cheves! I'm not mistaken, by gad!" The man fumbled for his spectacles. "My old eyes have been going back on me, Dick. Come here, man, and let me see you! Hardly knew you under all that gore," Ralston continued angrily. "That slugger, Pierre, came near bashing in your skull. I shall have to cane him, by gad! You've hardened, Dick...I see it! But you're Richard Cheves, of Cheves's Courthouse, Virginia. Three years since I've seen you. By gad, it's a wonderful thing to see your own kind after mixing with the 'breeds and puddin' eaters!" Of a sudden the old man's fingers dug into Cheves's arm. "What are you doin' in that British garrison and movin' around through the country with James Girty?" he asked fiercely. "Don't tell me you're a turncoat. I'll not believe that of a Virginian."

"I imagine, Colonel, we are both playing the same game, after the same ends," Cheves retorted shrewdly. "You went to a lot of trouble to catch one of your own fowls."

"Best catching John has done for a long while," said Ralston. "Dick, let me introduce John Harkness. I think we two are the only white American men left in Detroit." His voice grew sad. "They've weeded us out mighty fast. Were I not such an old and rickety and helpless-looking fellow, I think my turn would have come long ago. But they don't suspect me."

"How did you know I was with Girty?" queried Cheves.

"News travels fast," replied Ralston, sitting down. "I know more about Hamilton's business than he does himself." His eyes snapped with a quick fire. "I've got an organization that'll drain his little well dry some of these days. Oh, if I only had force to back up my information! Information my men get from right under his nose. We know every last one of his precious secrets. That bit of a dishrag, Hamilton! Pah! And that lumbering, barbarous, conceited Dejean! They can't down us, no matter how many men they line up against the wall or export from the country. They haven't been able to discover the leak yet. We've been too clever."

"I heard you did away with a ranger a short while ago," Cheves remarked.

Ralston smiled gently. "We play for high stakes, Dick. Can't always be too nice about the means. But a little gold found this fellow's heart. We didn't have to go farther. He's alive and safe and a good many hundred miles from here."

"Do you think it wise to tell so much," Harkness broke in quickly. "It may be that he..."

"What? Doubt a Virginian I've known since he was born?" said Ralston with irritation. "Why, I'd trust him with my life, as I do right now." He sighed. "Dick, if only I had something to strengthen my hand," he sighed, and turned to Cheves with a fresh interest. "You've come from the Illinois country. Tell me, what's goin' on down there? A bit of gossip came out from the Pennsylvania settlements last spring about George Rogers Clark going down the Ohio for some purpose. What's it mean? What'd he do?"

"That," returned Cheves, very soberly, "is why I'm here."

Excitement caught both men at once. "What for? Why?" queried Ralston, throwing the questions after each other. "I've heard mutterings and whispers and guesses and all manner of things come out of the lower country, but never any definite fact I could base hopes on. What is it?"

"I left Clark at Massac, seventy-five miles from Kaskaskia. He told me I should find him there, or that I should find him dead. He has a mind to take Detroit, if ever a fair chance comes. That's why I'm here, to find what Hamilton's plans are."

It seemed as though twenty years dropped from the colonel in the single jubilant gesture of his hand. "By gad, I can help then! My work hasn't been for nothing. My coming here was of use." He got up and strode around the room. "You've come for facts? I can give you nearly all you'll want. We'll scourge 'em out of the country! Did I tell you why I came here? All because, two years ago, Washington rode over from his winter camp and met me at Chester in the Red Lion Tavern...a few miles out of Philadelphia, that is...and asked me to come. He only said a word or so, but it uprooted me from Virginia and sent me here to do what I could. I worked a long line of alleged English connections, got into New York, rode into the Provinces as a loyalist and came here. I'll always remember one thing Washington said. 'It's possible that nothing may come of the venture, sir,' he warned me. `But someone must be in Detroit, for it may be that a force can get through. Then we shall need your information.' That's the thing which has heartened me to the task. And now it's to be used!"

"Well," returned Cheves, "it may come to pass. I've come eight hundred miles, and I've suffered a few times on the way. But that's no matter. If we can get hold of the Illinois forts and Detroit, that will be the end of the British in the Northwest."

Gray dawn had given away to the first approaches of the sun. Another fair day came, with its burden resting heavier on these men. They sat, each inspecting the other, hope struggling to overcome the odds of fear and sad experience. Throughout the talk one great question had been uppermost in Cheves's mind, and only pride kept him from asking it. He hoped that the colonel himself would let slip what he was most anxious to know.

"It would be months before Clark could get here," mused Ralston. "That would mean a fall campaign, snow, and privation, I'm afraid."

"You don't know Clark," returned Cheves, his mind only half on the conversation, for he was recalling the bitter memory of an ill-starred day when a duel and a note from a girl blotted out his dreams of happiness. Well, all that was now behind him forever. Doubtless she was managing the Ralston plantation, after the manner of the Virginia women, while her father struggled here in Detroit. Waiting at home with her heart set on that dog, Parmenter. An unreasoning wave of fear and jealousy ran through Cheves at the thought. No matter. As long as she chose to doubt him unjustly, he would never try to correct the error.

A light step sounded behind him, a door closed. He turned and on the instant had jerked himself out of the chair, standing very erect, ice and fire running through him. There stood Katherine Ralston. She had come from upstairs and was but recently risen; sleep still clung to the lids of her eyes, and the lusty blood of day had not yet filled her cheeks. But beyond all that she was beautiful. Yes, she was beautiful! Cheves, looking at her with a kind of pride-ridden, hungry despair, knew that whatever came in the years to follow he could not scourge the sweet vision of her from his heart. So he stood, irresolute, wishing he were gone, wishing he had the courage to take her into his arms, wishing he had not so much pride, wishing he had more.

For her part, a moment's inspection of this strange, bearded, blood-smeared man had not revealed his identity but, when he made the short bow and she saw the curl and color of his hair and recognized the mannerism of his movement, she knew. The flush of blood stained her cheeks, and a hand went up toward her heart. A dark mass of hair, done up in a loose knot, set off the sweet oval of her face, on which many contrasting emotions mingled—a high courage, pride, sympathy, and a sudden concern. Her father rose, his voice trembling just a bit as he spoke. "Katherine," he said, "do you recognize our visitor? The Lord never brought us a more welcome one."

She extended her hand.

"Richard, I...we are glad to see you here." The tone of the greeting, low and sweet, went to his heart like the barb of a Shawnee lance. With a remnant of old-fashioned courtesy, he took her hand and bent over it.

"I am glad to be here," he stammered.

She gave him a quick gasp. "What have they done to you! Your head!"

"Oh, that confounded Pierre!" Ralston's voice filled with anger. "John, you must watch that always. I've told you many a time there's no need for undue violence. We are not common sluggers, Dick. I hope you'll pardon us for the heavy blow."

Cheves laughed, and found himself surprised at the lift of his spirit.

"I've endured worse things," he replied.

Harkness flushed. He had been an interested spectator of this scene, his eyes seeking first the girl's face, then Cheves's. Now he turned to the window.

"It's as the colonel says," he explained shortly. "A fortune of war. How was I to know?"

"'Tis nothing," assured Cheves.

Katherine turned to the kitchen. "Richard, come with me," she directed. "We must fix that cut before it gets worse."

Cheves followed her out, with the unsmiling eyes of Harkness staring at them both. By the time the Virginian got to the kitchen, she had already filled a basin with hot water from the tea kettle. From some small closet she drew tattered bits of linen and cotton cloth, ripping these into regular strips.

"Sit in that chair," she commanded. "All night with your head in the cold. What a savage, unkind country this is...even with men like my father and John. I wish I had known!"

His heart jumped at that and, the next moment, sank. After all, she would have felt the same pity toward the worst, most degraded man in the Northwest. His face drew tighter.

"Do I hurt you?" she asked.

"No. I was thinking of other things."

She sponged the last of the caked blood into the pan and began wrapping the bandages about his head.

"You are always thinking of something far off, Richard. It has always been that way." A trace of sadness came to her words. "Am I so depressing as all that?"

Depressing! Good Lord! Cheves thought. "I was only thinking," he replied aloud, "of why you did this for me since I am what you believe me to be...what another man said I was. Why do you do it?"

"Let's not quarrel again, Dick. Time changes so many things. So many, many things." She started to say something else but stopped. Cheves, wrapped in his own thoughts, struggling with his own desire to utter his grievance, did not note the implication of the unspoken words.

"Time!" he said bitterly. "Time doesn't do a thing save score the old wounds deeper. Never tell me that time softens anything. I've sat awake a hundred nights, trying to puzzle things out...and can't."

"Dick..."—her voice fell low—"there isn't so much to puzzle over."

"Parmenter," he broke in. "You believed him, let him paw around your sympathies, and never listened to a word from me."

"Richard, you never came to explain! What was I to think? I saw you knock him down like a street bully. The next day you nearly killed him in a duel. I heard people whisper. Nobody told me a thing. I grew angry at what you had done to him and wrote you that note...and you never came back! Oh, that was the thing which hurt me so much! You never came back to explain! I would have listened!"

The mulatto had left the kitchen long before. They were alone, fighting out the battle so very, very old, stumbling across new facts that seemed to change the whole face of the quarrel, trying desperately to be fair, to tell all without hurting, trying to keep pride from spoiling everything again.

"And then Parmenter came to you, and you believed all he said...that I was a bully and a liar," Cheves charged.

"For a while, Dick, just for a while. Then I knew him better and sent him away, to tell you to come back. And you didn't come!"

"Sent him away?" Cheves turned swiftly.

She nodded, eyes clear and brilliant. "To tell you to come back."

He took a deep breath. "He never told me that. When I saw him at Wheeling, a year ago, he never told me that. He said you had promised to marry him, after the war. He came down the Ohio with me from Fort Pitt...and told me you had promised him..." A great overwhelming weight seemed to be slipping from Cheves, and a new hope came in its stead. "Oh, what a mess I made of it!" he groaned. "I didn't know."

"Time...time does so much," she said wistfully. "Richard, while you were gone, I found...I found..." and again she failed to say the thing within her. But now he heard the pause, sprang up, and came closer.

"Found what?" he insisted.

She summoned her courage, keeping her eyes upon him in the mute hope that he might not misunderstand. "That there never was any man, Dick, save you. It doesn't matter now, I guess. But whatever happened, I didn't care what you had done. There never was a place in my heart for Danny Parmenter."

She was in his arms the next moment, crying in small, stifled sobs. As he kissed her, she whispered, "It has been so long."

The mulatto's footsteps drew them apart.

"We had better go back to Dad now," she said, and in the hallway she leaned up to him and whispered, "you queer, dear man! Never leave me like that again. Don't you understand a woman?"