RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

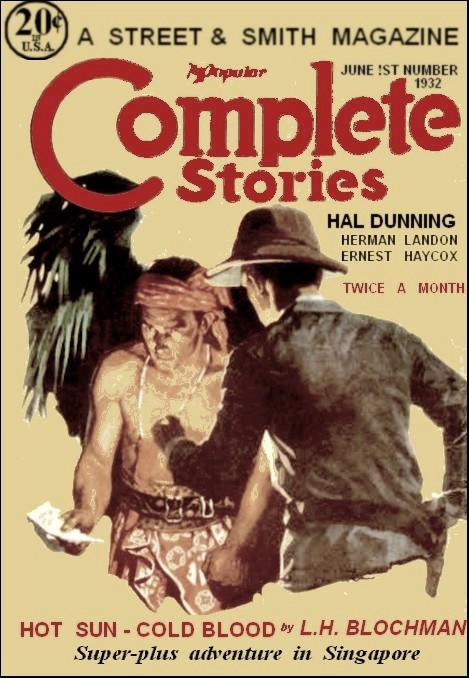

The Popular Complete Stories, 1 June 1932, with "The Kid From River Red"

THE stage road came out of the open and smoky south as straight as a string, dipped across a small depression and strained toward a pass between the northern buttes. Right where the wagon ruts cut into the depression lay the youth from River Red, gray clothes blending with the sandy soil and some of that soil heaped over him to make the concealment more effective. He had a shotgun cuddled to his side, a floppy coat, a bandanna pulled up over his face, and a drab hat jammed over his ears. Between the rim of the hat and the edge of the bandanna nothing was revealed but the bright, eager flash of agate-blue eyes; and these eyes were at present immovably fixed on a train of dust kicked up yonder by an advancing stage.

In all the length and breadth of the desert no worse a place could have been found for a hold-up. There wasn't a tree or a butte or a rock within three miles, and, though a circling line of bald ridges ran east and north of him, about twenty minutes off these made a perfect view for anybody who might be watching the youth's antics. To make the situation more dangerous, he had left his horse in the only roundabout arroyo deep enough to conceal the animal, and this was fully eight hundred yards removed. But all great artists work with original ideas, and the youth from River Red had embarked on an outlaw's life with a most definite belief in his own toughness and ability. He was scarcely sixteen and so far had a clear record—except for, perhaps, the occasional appropriation of a maverick, which in this land and time was less than no crime at all. Briefly, he awaited the stage here because nobody would ever think of such a thing.

Meanwhile, the stage, doing a good twelve miles an hour, rolled forward. Presently the outline of it became distinct, and the youth saw there was but a single man, the driver, sitting on the box; and, when he noted this, a grunt escaped him to indicate both relief and disappointment. One man was easier to handle than two, but an unguarded stage meant skinny rewards. Looking about him, eyes almost violet with excitement and intensity, he inspected the hills to his left and rear. Also, he mentally measured the distance to his horse and again figured the time it would take him to run that far. These things checked, he turned back to the immediate business in hand. The stage rolled on, great flares of dust spouting up into the sun-scorched sky. The clank of chains became audible, also the combined groaning of wheels and singletrees. Sinking a little lower, the youth nursed the shotgun forward and brought his knees beneath him. He cleared his throat, muttered something to himself, and flicked a palm underneath the hat brim to halt the streaming sweat that bit into his eye. When the stage was so close at hand that he saw the driver's face, staring directly between the near animal's ears, he leaped from the depression, charged aside, and swung the shotgun against the driver's body.

"Draw up!" he yelled, voice cracking slightly. And when he heard it, he cursed and yelled again. "Draw up!"

The driver, old Lew Lannigan, had been handling ribbons for thirty years, and it was not in any sense a new story to him. He had no intention of displaying resistance, for he considered it no part of his duty to argue with outlaws. But what did send his hand more swiftly than usual to the brake rod was the tremor of excitement in the road agent's command. Having seen the business end of a gun a great many times, Lew Lannigan well understood how dangerous a thing it was in the fingers of a nervous one. Therefore, his promptness in jamming on the brakes. The stage curved into the depression, sprang violently up from compressed springs, and halted dead abreast the youth from River Red. It was a nice maneuver. The driver was in a poor position to fire even if he chose, and the passengers of the stage were under full control. A woman inside screamed, and another woman said: "Donna, stop that squealin'. Haven't you ever been held up before? Think nothing about it."

"Keep your mittens elevated," said the youth definitely. "Passengers step out."

The coach door opened, and a woman—young and handsome and smiling slightly—stepped to the ground. Following her came another woman, no more than a girl and not smiling at all; she had the oval, dusk-tinted face of part-Mexican blood and dark, liquid eyes that watched the youth in evident fright. The youth was for some unaccountable reason impelled to reassure the girl. "No fear," he said with a broad condescension. "I never hurt a lady in my life. I prey only on corporations. Stand fast just a minute and it will soon be done. Mister Driver, reach down with one hand and throw off the express box. No monkey business...throw it clean out here."

The driver shifted his tobacco and obeyed, swinging the box out from beneath his seat and landing it directly at the feet of the youth. "Yore trouble is goin' to be poorly repaid, fella. Nothin' much in that box today."

"Too bad," grunted the youth calmly. "But the experience is worth as much as the money to me."

"I'll estimate you'll get plenty experience," agreed the driver. "Robbin' a stage ain't half the fun. Other half comes when a posse fogs you around the landscape. Whut possessed you to tackle a stage out here?"

"Never expected me to pop up from the ground, did you?" asked the youth, quite apparently enjoying his triumph.

"It's an unlikely spot," said the driver, and let his eyes roam across the hills.

"That's why I did it here," explained the youth. "My style's to hit 'em where they ain't. You'll hear more of me."

"Speakin' with due respect," grunted the driver, "you better cut the palaver and send us on our way. Should a bunch of riders pop out of the pass yonder, you'd be in a pickle."

The youth bowed to the ladies. "You are at liberty to proceed," he said quite formally.

"Thank you for being so kind," said the older of the two. She had hazel eyes that seemed to smile independently of her lips. "I shall remember so gallant a bandit." With that, she entered the coach. But the younger one, whose Mexican blood cast so pleasant a glow over her face, had regained her composure. She stared severely at the youth, saying—"Señor, you frighten me."—and hurried into the vehicle as if frightened by her own boldness.

"Didn't mean to hurt you one bit," asserted the youth, taking a step nearer.

The driver's ironic voice came down. "Let's cut out the lollygaggin'. I got a long trip to San Juan."

The youth sprang back, gun stiffening on the driver. For one brief instant he had allowed his attention to wander, and the thought of what might have happened to him brought a pale flare of anger to his bright eyes. "Don't try nothin' on me, Mister Driver!" he ground out. "I'm not the man to monkey with. Get goin'...and go fast."

"Ain't I scared?" grunted the driver under his breath. Releasing his brake, he set the horses in motion and drew out of the depression. Twenty feet off he turned to yell. "Leave that box beside the road where I can pick it up on my way back trip. You won't need it." Then the stage retreated with banners of dust whipping high behind it.

After a moment's watchfulness, the youth unbuckled the straps of the express box, shot away the lock, and threw back the lid. There was nothing at all in the bottom of the box, but a kind of corner compartment held a promise. Opening this, the youth found a packet of papers about as thick as his fist, and, when he riffled through it, a gaudy assortment of purple and yellow printing met his eyes. But as young as he was, he knew these things were worthless to him. Though each sheet represented money, he knew that it was money in some mysterious form that only bankers knew much about. To him it was a worthless haul and his first introduction to an important fact concerning outlawry: money had a manner of assuming many useless shapes.

The youth accepted the turn of fortune philosophically. "Oh, well. Better luck next time. But I held up a stage, didn't I? I got experience. Now I better drift."

Turning, he ran along the depression as it curved and deepened across the desert. When he came to his horse, he mounted, left the arroyo, and pointed for the eastern ridge. Half an hour later he was well sheltered on the heights, watching the trail behind. Nothing moved off there.

"They better stay clear of me," he muttered, "or I'll run 'em bowlegged."

So observing, he got down and unwound a blanket roll tied behind the saddle. In it was a change of clothes that he proceeded to swap for the old ones—new hat, coat, and pants. The discarded garments he rolled in a tight bundle, added the bandanna, and—after some thought—the packet of non-negotiable securities. Any number of rocks offered him a hiding place, and he buried the bundle in a regular cairn. This deed performed, he again got to the saddle and rode at a rapid gait through one ravine and another for perhaps eight miles, or until he arrived at a trail due east and west. This he took, traveling now a little more leisurely. And about the middle of the afternoon he came to San Juan, just a blue-eyed and slightly gawky youngster as the town had seen many thousand times. If his glance was sharper than to be expected in one of his age, or if his features held a preternaturally pinched and poker-faced gravity, it was not really extraordinary. In the hot and fecund Southwest, boyhood was often a brief affair, and manhood came too frequently with a cruel suddenness. Still many seasons shy of majority, the youth from River Red could truthfully say he had neither home nor parents, and that he had done the full work of a man since twelve. Outlawry was for him a release from drudgery and a distorted revival of that play impulse that had been practically crushed out of him.

His entry was somewhat hesitant and wary, but, after he had drawn up at a saloon hitch rack and dismounted, and after finding himself to be no target of accusing eyes, a measure of swagger came to him. He raked San Juan's single street with a regard that was both alert and patronizing, as befitted one who had boldly invaded the camp of the enemy. He regarded the stagecoach standing by the stable, the drowsing Mexicans, the few frame dwellings mixed with the inevitable adobe structures. Having thus conducted his tactical reconnaissance, he entered the saloon—immediately to find the stage driver there. Lew Lannigan was explaining the hold-up to an interested group in laconic phrases.

"In a place, I'm sayin', nobody but a durn fool would ever think of holdin' me up. He'd never got out of it alive had a party come from the pass unexpected. Well, I braked down sudden. You bet I did. I'm paid to handle a ribbon, not to guard no express box. Moreover, that road agent was nervous. Plumb nervous. I saw his hands shakin'. That's what like to scared me stiff. Never can tell what a nervous fella will do."

The youth from River Red breasted the bar and motioned for a drink. A red color stained his neck, and his ears began to bum. Nervous? Like hell he was. Drinking down his potion like a veteran, he felt a great urge to put that old, leather-faced buzzard right on the subject. Killing the desire, he brooded darkly. Next time he held up a stage he'd get that fool off the box. Make him dance. And say: "Nervous, was I? Never make allusions about your betters, see? I stood within five feet of you in San Juan and heard the brag you made. Be careful, mister, and don't do it again. You keep your mouth shut and don't monkey with the hand of doom." That's all he'd say.

Having completed his narration, old Lew Lannigan moved to the bar for a drink. His eyes fell casually on the youth, focused, and remained intently still for a moment. Presently he swung to the bartender. "Where's Buck Duryea?"

"The sheriff?" countered the bartender, putting a slight edge of sarcasm on the words. "Why, now, he's off chasin' Dusty Bill some more."

"I got to tell him about this affair," said Lew Lannigan. "You think that it was one of Dusty Bill's men that held you up?" inquired a spectator.

"Naw," grunted Lew Lannigan. "Dusty Bill or any of his men would know better than to pull it like that. And Dusty Bill would know blamed well I didn't have any money in the box today. His source of information would keep him from pullin' a johnny on an empty stage. Moreover, did you ever hear tell of any man in Dusty's crowd being nervous?"

The youth from River Red pricked up his ears at the mention of Dusty Bill's name—Dusty, the scourge of the land, the outlaw of outlaws.

Lannigan said: "Well, here's more grief for Buck Duryea."

"He'll pay no heed to you," declared the barkeep. "All he's worryin' about is chasin' Dusty Bill."

"That's what he was elected for...and that alone," said Lew Lannigan.

"He'll never fulfill the election promise," replied the barkeep, still ironic.

Lew Lannigan shook his head. "He'll come as close to doin' it as any man in the country."

"Which ain't very damn' close," maintained the barkeep. "I'm no friend of Dusty's, but I'll assert he's just about six too many fur anybody around San Juan. Buck Duryea's a good guy. Sure he is. But good guys die sudden when they monkey with Dusty Bill."

"Well, if I was the road agent that held up Lew Lannigan," added another bystander, "I believe I'd breeze outta the country. Dusty's men won't stand fur any competition in the outlaw trade. It's a closed market...and all his'n."

The youth from River Red toyed thoughtfully with his glass and kept his attention subdued at the bar; once he essayed a quick look about him and found Lew Lannigan's glance on him, a slightly speculative glance. But it was soon diverted elsewhere. Lannigan poked a bystander in the ribs and muttered: "Will you observe who is payin' San Juan a visit. Teeter Fink, no less, and ain't he got brass?"

The youth turned. A grotesque, scarecrow figure darkened the saloon doorway, slouching silently there a brief interval. His clothes were ragged and in keeping with a flat, gangling body surmounted by a bearded face. Out of that tangle of whiskers sparkled a pair of the deepest, darkest, most inquisitive eyes the youth had ever seen. At one sweep those eyes absorbed the saloon interior, its contents, and its significance. Then Teeter Fink passed on. Lew Lannigan paced to the door, and from this point of view reported the man's progress.

"He's gone to Magoon's store."

"That's just where you'd expect him to go," grunted the barkeep. "But whut brings him to town? Answer me that?"

"Plain enough," said Lew Lannigan. "Dusty Bill wants to know something, and he's sent Teeter Fink to find out. Ain't I said Dusty's got the best information-getting system in this country?"

"Too bad the sheriff ain't here to ask Teeter where Dusty Bill's hiding," was the barkeep's malicious observation.

Lew Lannigan turned to look in the opposite direction. He grinned slightly. "Oh, I dunno. Here comes the sheriff now."

"Judas Priest!" breathed the barkeep. "Whut'll happen when he sees Teeter Fink?"

The youth from River Red left the bar and went outside, casually passing Lew Lannigan and pausing at the edge of the saloon porch. A cavalcade filed in from the east, half a dozen drooping, dusty men with the glare of the westering sun cutting bronzed features into bold lines. Studying the leading horseman, the youth from River Red instinctively knew him to be the sheriff, Buck Duryea. The mark of authority was too plain to be missed. Duryea was tall, slim, and surprisingly young for his job. Cast in much the same mold as the average Western rider, there was at the same time a subtle difference in his bearing. The face of the man was firmer, more watchful, and touched with care. Above a bold chin and an equally bold nose rested a pair of gray, searching eyes; and, as he came abreast the saloon and turned his head toward the porch, those eyes fell on the youth. It was an odd feeling that shot through the youth then. Instantly he went on the defensive; instantly he summoned the full poker mask to repel the cool, careful scrutiny the sheriff gave him. But it lasted only a moment and was ended by a courteous bow on the sheriff's part. Not understanding just why, the youth from River Red bowed back. Afterward, the cavalcade passed on to halt in front of another building and to dismount there. The sheriff went inside, followed by his men.

The youth from River Red tapered off a cigarette. Not a bad gent, he admitted reluctantly to himself. A man could like him. Kinda tough to consider him and me will probably battle it out someday. Can't let sentiment interfere. Posted there, the youth waited and watched for developments, observing that other men, some of them seeming pretty responsible figures, followed the sheriff into the building.

INSIDE the sheriff's quarters of the San Juan courthouse, Buck Duryea settled to a chair and built himself a cigarette. The other members of the posse assumed their several attitudes of relaxation, patently weary and pessimistic. Lon Young, the sheriff's chief deputy, looked at Duryea with an owlish disfavor. "Well," he grunted, "there's the end of another wild goose chase. By thunder, I'm ridden down to one big callus!"

"Didn't expect Dusty and his boys to be on the spot waitin' for us, did yuh?" drawled Buck Duryea.

"We're doin' a lot of runnin' around for no good purpose," said Lon Young.

"That's percentage," offered Duryea. "We'll have to follow twenty cold trails to get a warm one."

"Seems a fool caper to me to hike off on every floozy whisper we get," objected Lon Young, and looked around him for support. But the rest of the crowd was silent, and Young's rather thin mouth narrowed increasingly. He was a sorrel-colored man, lean as a lath, and naturally taciturn.

"Never can tell which one of these whispers is the right one," was Duryea's patient rejoinder.

"I doubt 'em all," said the deputy.

"Sure," agreed Duryea. "You'd doubt your own parentage, Lon."

The deputy was about to snap out some testy reply when other men began to file into the office—older and more deliberate men. One of them, a rugged and middle-aged character with a dogged chin, closed the door and took a chair one of the posse members rose to offer him. Buck Duryea cast away the cigarette and squared around. "Not this time, Dane. Cold trail again."

Henry Dane laced his fingers across a substantial paunch and considered the information gravely. This was his habit, to ponder and to debate internally. In others it would have aroused resentment, but Henry Dane was too great a figure in the land to trifle with. In some small measure of truth it had once been said of this man that a tenth of all the shoes in America were made of leather off his cows; therefore, the West opined that, if pondering was responsible for his material prosperity, it might be well for people to indulge the habit.

"We'll never get him," said Lon Young. "I'm tellin' you that."

"You boys discouraged?" queried Dane quietly.

Sheriff Buck Duryea broke in. "Lon is speakin' for himself. He's always discouraged on an empty stomach. I have said before and I will repeat now that I was elected on the single platform of gettin' Dusty Bill. I'll live to see it through, or I'll die tryin'. But it will take time. I'm going at this my own good way."

"Proper," approved Dane. "That's why the cattlemen of the county picked on you, Buck. You don't wilt easy. Now listen. The Association held a meetin' at my ranch yesterday and increased the reward on Dusty to ten thousand dollars. Also to five each on the heads of his followers...Baldy Zantis, Sam Ellen, Tom DeStang, and Colorado Clarney. That's all of 'em, ain't it?"

"All he has left of his gang," agreed Buck Duryea. "He's pared 'em down to the best and most trusted fighters."

"Lot of money on those fellows," grunted the deputy.

"Maybe," said the cattleman, "but it ain't one-fiftieth of the harm Dusty Bill's done to the name of the state and to the prosperity of this county in particular. Dusty's outlived the old, hell-roarin' times, and he don't seem to realize it. When he goes down, we'll be enterin' a new age, but, until he goes down, San Juan's still what the rest of the country is pleased to call us...the land of shotgun law. Now, Buck, the Association agreed to do this if you approved...to establish a posse of ten men at each of about four settlements so that no matter where you may be on the chase, you can get reinforcements in a hurry."

Buck Duryea thought of it a little while and finally shook his head. "That'd be too many riders clutterin' the landscape. It ain't more men I need, Dane. Dusty can ride through a hundred as easy as he can dodge the six I've got here. I've considered this a long time, and the thing's clear to me. I'll keep ridin' and keep my ear to the ground. Sooner or later there'll be a break, and, when it comes, I'll move into action."

"We'll be ridin' forever," stated Lon Young.

"I don't think so," replied Buck Duryea. "Dusty Bill's a cagey, clever devil, and he figures his moves mighty careful. But there is this kink in his nature...when he's pressed about so far, he loses his temper and all his caution. He bets reckless and strikes back like a crazy man. That's what I'm waiting for now. And," continued Duryea, casting a speculative glance around the room, "I have a hunch we won't have so long to wait."

"What makes you think so?" demanded Lon Young, suddenly interested. But Duryea only shook his head.

Henry Dane frowned a little. "There's one danger you shouldn't overlook, Buck. With all this dashin' about, from one place to another, you may be drawn off guard yourself and fall into a trap. And I'm sayin,' if Dusty Bill ever does pull you into a trap, it'll be a wicked one. That's the kind he sets. Consider it well. Dusty Bill has no compunctions about linin' you up for slaughter."

"Correct," agreed Buck Duryea. "I'm watchin' my step. It'd be just like him to make some hell-roarin' play to wipe me and the boys off the map at one move."

Henry Dane changed the subject abruptly. "You know the stage was held up today? And that Teeter Fink's in town?"

Buck Duryea straightened alertly. "The mornin' stage? Well, I better look into that."

"Lew Lannigan's got the dope," said Dane. "But what interests me is Teeter Fink, breezin' around here. He's got a damned inquisitive pair of eyes and plenty sharp ears...and he is Dusty Bill's spy, body and britches."

"I'm leavin' him alone," said Buck Duryea quietly. "Just between us, I consider Teeter Fink to be one of Dusty's weak points. Teeter's goin' to give that gang away one of these days. Leave that to me, Dane."

"Good enough," said Dane, and rose.

The meeting dissolved, and men strolled out to the street.

Buck Duryea stayed behind a few minutes to consider thoughtfully the flat surface of his desk. There was a map of the county spread on it, a map across which lines had been lightly traced with a pencil. Looking at these, Duryea shook his head.

"Won't do much good to try to plan anything definite. Dusty jumps around too much. I'll just have to keep moving and wait for the break. He's a gambler...and so am I." With that, he left the office.

Lew Lannigan saw him and crossed the street immediately. "I heard about the hold-up, Lew," said Duryea. "Lose much?"

"It was an empty express box," explained Lannigan. "But what gets me is where he pulled the job...just two miles short of the pass and plumb in the open. And him nervous to boot."

"That lets out Dusty's bunch," reflected Duryea. "None of that gang knows what nerves are. Who's the kid roamin' towards Magoon's store?"

The stage driver turned to find the youth from River Red moving casually along the far sidewalk. "Him? Dunno. Thought I sorter reco'nized him once, but I guess I don't. Some new punk..."

There was a sudden yell of alarm and a warning, followed by the sound of pounding hoofs. Swinging about, the sheriff saw trouble. A team hitched to a light rig had backed away from a hitch rack near Magoon's and was now breaking into a plunging run. For one moment the horses were within control; the next moment the effort of a man to intercept them added the extra measure of fear. They broke madly, straining away from each other, rig careening from side to side. A greater shouting rose, and a woman screamed. Leaping forward, Buck Duryea saw this woman trip in her effort to cross the street and fall directly in the path of the oncoming brutes. As the sheriff ran, his arm went toward his gun. But the impulse was defeated before it got under way, for the townsmen lining the far building wall were in a direct line with any shot he might make. Turning slightly, he aimed for the girl, now half risen. A slim figure came into one corner of his vision—it was the youth from River Red—and dropped to a knee. Almost simultaneous with that move a single gunshot crashed like a dynamite explosion through the town, and the off horse of the team sagged. Buck Duryea halted in his stride, caught up the girl, and pushed her aside. Dust rose in great yellow sheets, and the remaining horse, brought to a halt by the anchoring weight of the dead one, fought with an unreasoning fury in almost the exact spot where the girl had been—bucking against the harness and kicking the rig to splinters. The men of the town ran forward, and a tide of excited, contradictory talk rose.

Buck Duryea had shoved the girl against the saloon porch, but he caught up with her again and held out an arm to keep her from falling. "Take it easy, Donna," he said. "You're all right. Excitement's finished."

The girl lifted her face, all the pert prettiness gone out of it. "Señor Buck...I fell! Thank you...thank you!"

"Sure," soothed the sheriff. "But don't thank me. Thank this lad that got in a good shot."

The youth from River Red stood beside the porch, attempting to assume a nonchalance that only accented the awkward self- consciousness about him. "Shucks," he grunted, "that wasn't nothin'. I could make that shot ten times out of ten."

The girl looked at him with wide, deeply dark eyes and made a small curtsy. "You are ver' brave, señor. It is to you I owe my life."

"Nothin' to it," said the youth, increasingly embarrassed.

The girl's brows arched a little, and her glance seemed to dig into him more. "My name," she said, after a pause, "is Donna Chavez." Then she turned and hurried away.

Buck Duryea reached for his cigarette papers, eyeing the youth. "That was quick thinkin', old fellow. And a damned good shot. You don't look so ancient, but you certainly carry an old head on your shoulders."

"It ain't age that counts," said the youth with an air of tolerant wisdom. "It's experience. Experience is the thing. I've had lots of it."

"Good enough," drawled the sheriff. "Don't believe I've seen you before. New here?"

"Yeah. I'm from River Red."

"That would make you the River Red Kid," considered the sheriff, well knowing that such a name, given under such circumstances, had all the effect of a medal. The youth pursed his lips and struggled to maintain his manner of grave assurance.

"I reckon," he admitted. "One name's as good as another when a feller's traveled around considerable, like me."

"Sure," approved the sheriff. "Come in today, I suppose. Strange that I didn't happen to meet you on the road."

"I come straight from the east," said the youth swiftly.

Duryea nodded and turned away. "If there's anything I can do for you," he called back, "be sure and let me know. One good turn deserves another."

The River Red Kid muttered something that Buck Duryea didn't quite catch. For that matter he dismissed the youth completely from his thoughts almost on the moment. Going along the walk, his eyes narrowed on the doorway of Magoon's store, inside of which Teeter Fink and Magoon were undoubtedly hatching up some sort of hell. He had nothing on Fink, but, nevertheless, the bushy- bearded man carried the secrets of Dusty Bill's bunch in his head and was everlastingly faithful in his performance of that outlaw's orders. Something of more than average importance had brought Fink here today. Turning that belief thoughtfully over in his mind, Buck Duryea passed into the store to catch Fink and Magoon deeply engrossed in a subdued conversation that came to an abrupt halt. Teeter Fink swung around defensively and stared at the sheriff with an open defiance.

"Nice day, Teeter," observed the sheriff. "Come from your mill?"

"I did, if it's any of your business," grunted Fink.

"Seen Dusty lately?"

"I'd be tellin', wouldn't I?" jeered Fink. "Don't try to spy around me."

"But you've seen him in the last day or two," pressed the sheriff casually.

"What of it?" growled Fink.

"Nothing much," drawled the sheriff. "But, when you see him again, you tell him I heard of his little boast to the effect he was goin' to shoot me in the back like a dog. The inference bein' I'd be runnin' away from him at the time. Also tell him the statement is some wide of the actual truth."

"You tell him," snapped Fink, and deliberately placed his back to the sheriff.

Magoon, the storekeeper, looked on with a heavy-lidded passiveness. Buck Duryea turned slowly and walked into the hot afternoon's sunshine with a dissatisfaction boiling up in him. Story there, he reflected moodily, if I could just get it. Dusty's told him to come in, for some good and sufficient reason. What's the reason? Something's in the air and has been for the last forty-eight hours. If I don't look sharp...

"What are you scowling at, Buck?"

He lifted his head to find a rather tall and pleasant-faced girl standing directly in his path—that same girl who had smiled through the stage hold-up. Buck Duryea reached for his hat, the gravity on his cheeks relaxing somewhat. "Hello, Anne. Thought you were visitin' at Fort Smith?"

"Came back," said she, equally laconic. "Got lonesome."

"For me, I suppose?" countered Buck Duryea, grinning. "Might be some truth in that, Mister Duryea."

"If that's a hint," said Buck, "stay around a while and let me entertain you. Where's your adopted orphan child?"

"Donna? In the house recovering from the shock of that wreck. Poor girl, that's the second scare she got today."

"As how?" queried the sheriff.

"Haven't you heard? She and I were in the stage that got held up. Donna thought she was going to be captured. But really the road agent was nice about it. Bowed and scraped. He must have been a philosopher for when Lannigan told him the express box was empty, what do you suppose he did? He said it didn't matter much because the experience was more important. Can you feature anything more funny?"

Buck Duryea's attention, which had been more on the appearance of Anne's clear, slim face than on her words, suddenly came to a definite focus. "He said what?"

"That experience counted most," repeated Anne. "Why?"

"I've heard that remark from another source real recent," said Buck Duryea, softly alert. "Something to look into. A man's mouth often gives him away, Anne."

"You're so up to your ears in trouble," said the girl, "that you don't hear half what I'm saying. Buck, do you want to know what really brought me back from Fort Smith? Listen. I heard a very strange and disturbing thing over there. It's such a creepy, horrible thing that I couldn't sleep last night. Everybody knows it...everybody's whispering about it. Buck...you and your men are to be trapped, lined up, and shot down! That's why I'm back...to warn you."

"Sounds like a typical Dusty Bill scheme," opined Buck Duryea.

"Don't take it so lightly!" exclaimed the girl. "It's spoken of as if the outlaws had the trap all set and ready for you! I asked questions. Naturally, nobody told me any more. But I came back in a hurry because I gathered this killing was to be done within a day or two. Buck, you've got to watch yourself."

"I'll try, Anne," agreed Buck, and swung off in the direction of the courthouse. A man—one of his posse members—came idly down the street, and Buck Duryea stopped him and issued a quiet order. "See that kid lounging by the saloon porch, Alki? The one with the long nose and the yellow hair? He said he came into town by way of the eastern trail. Now you lope back on that trail about ten miles and inquire of the settlers along the road if they saw a boy of his proportions pass by."

"Okay," said the posseman, and strolled off.

Going into the office, Buck Duryea dragged a chair by the window and sat down. In a little while he saw Teeter Fink ride by, outbound from town. Almost directly afterward the River Red Kid got to his horse and likewise left the street.

Just a youngster, grunted the sheriff to himself, and plenty of stuff in him to make a good citizen. Can't let a boy like that go bad...it ain't right. What's his part in this business, anyway? Something's smoking up, and I've got a hunch it won't be long now.

THE River Red Kid had loitered on the saloon porch with a purpose, which was to keep track of Teeter Fink. And when the latter left San Juan, the Kid followed at a discreet interval. But directly after leaving the town behind, the Kid changed tactics and rode into the hills to the south. At the end of ten minutes he was quite buried in the rolling ridges and ravines. From one high point he saw Fink curving down the main north and south stage road, and, varying his course to conform, he presently fell into the stage road a little beyond the pass. By and by he heard the sharp tattoo of Fink's fast-traveling pony, and instantly the sharp, blue eyes began to freshen with excitement. He knew the danger of this sort of meeting, but even so he dared not risk turning about to confront Fink and arouse the other's suspicion. So he idled onward, slouched in the saddle and making his ears do double duty for him. Fink had slackened speed, once appearing to halt entirely. A little later the outlaw's henchman swept forward at an impatient pace, came abreast of the Kid, and reined in. Fink's piercing, brilliant, black eyes seemed to stab the youth.

"What you doin' here?"

"Waitin' for you," said the Kid evenly.

"Yeah?" grunted Fink, openly hostile. "Whut for?"

"I want to join Dusty Bill's gang," was the Kid's astonishingly calm proposal.

Fink's eyes narrowed to slim apertures of harsh light. "Whut makes you think I know anything about Dusty Bill?"

"Heard it said in the saloon," said the Kid. "I'm a great hand to pick up things."

"Yore just a punk," stated Fink, "and you got a god-awful nerve bracin' me thisaway. Don't you know what happens to folks that get too cur'ous?"

"You got me wrong. I'm not curious. I want to join Dusty's gang, and I want you to let me see him. I ain't no punk, either. I been places, and I done things."

All this while they were riding side by side into the open desert. Teeter Fink was probing the Kid with a constant, aggressive inspection. Suddenly he laughed sardonically. "So you think I'd fall for that guff? Go on back to Buck Duryea and tell him it's a poor play. Sendin' kids out to trap folks like Dusty...if that ain't a hell of a note. Now you beat it!"

"Don't believe me, uh?" asked the Kid. "Well, look ahead on the ground there."

They were, by this time, approaching the depression where the stage had been held up, and the River Red Kid's pointing finger indicated the abandoned express box. "I did that," he added.

"You?" boomed Teeter Fink. "How many more damn' lies you goin' to tell me?"

"Want proof?" challenged the Kid. "Turn off to the hills. I'll show you I did it."

Fink halted and faced the Kid. "What kind of proof?" he wanted to know.

"What I took out of the box," said the Kid.

A cold, shaft-like flash of light emerged from the imbedded eyes of the go-between. Suddenly he nodded. "All right. You show me."

They set off beside the arroyo, followed its ragged course, and tackled the foothills. The River Red Kid confidently led the way up a widening ravine, turned through one lesser alley and another, and at last halted. Dismounting, he approached a pile of rock. But, just short of it, he swung around to face Fink and very shrewdly said his say. "You move over so I can keep you in sight better. I know what you came up here for...to get anything valuable I might have and leave me flat."

A change came over Fink's face. He stiffened, relaxed, and prodded his pony a few yards aside. The youth, still maintaining a watch on the go-between, rolled the rocks aside and retrieved his bundle of clothes. Opening the bundle, he took out the packet of securities and held them up for Fink to see. "That's what I got. But they're no good for fellows like us."

"No money?" queried Fink, visibly disappointed.

"Nope. But it shows you I held up the stage, don't it? I'm no spy of Duryea's. I want to join Dusty's gang. You goin' to take me to him?"

Fink apparently had already made up his mind. "You come with me," he said. "I ain't promisin' you anything, see? But yore too damn' inquisitive to be floatin' around the landscape like this. Ride right beside me."

The Kid left the clothes lying there but tucked the securities in his pocket. Mounting, he ranged beside Fink, and so they passed on along the rugged spine of the hills, saying nothing at all. It was sundown, with the last, long shafts of the sun exploding riotously in the sky. Then twilight came and held on for its brief period of calm, empurpling beauty. Fink began to cast his eyes more alertly behind and beside him as they fell into the deeper contortions of the hills; his manner became more guarded, more constrained. At dusk they came around a bald butte and faced a bowl-like clearing within which sat a mill beside a creek, a rambling house, and a few outsheds. Nothing stirred here; no kind of life was evident; no beam of lamplight broke the graying fog. Fink began to sing a loud, unmelodious song about a girl named Annie Lee, but after the first dozen words ceased. Coming to the front of the house, he got down and ordered the Kid to go in ahead of him.

"And be damn' careful in yore acts," he warned. "Do just what I tell you to do...no more, no less."

The River Red Kid passed into a dark room, stale with tobacco smell and still containing the stifling air of the hot day past. Fink passed him, lit a lamp on the table, and walked to another room, closing the door behind. Another and more remote door banged shut, and somewhere was the faint, indistinguishable murmur of a voice. After that, he heard boots pass quickly across the floor, and in a little while horsemen—two or three of them—rode out of the clearing in evident haste. Through all of this the River Red Kid remained silent and steady. Once he shifted so as to put his back to the wall, and his eyes, again deepening to violet, scanned every crack and cranny of the place. Sweat began to trickle down his forehead to indicate the ordeal he was passing through. For he was no fool, and he understood what might well enough happen to him at the very turn of a word or lift of an eye. But, stolidly clinging to his established and definite purpose, he waited out the situation.

A door opened, and a stranger came through with a queer, cat- like suppleness of stride. He was not much taller than the River Red Kid but obviously matured and seasoned. His face had a strange lightness about it—lacking the usual deep tan and the usual weather lines; at each lip corner the curve of his mouth ran slightly upward to pull the flesh slightly off the teeth and so give him the aspect of continually smiling. His eyes, as well as the River Red Kid could determine, were a shade of pale slate and oddly large and =winking. In fact, he seemed as he stood there on the balls of his feet to be lacking the usual muscular tremor and restlessness of the average man. The Kid quelled a twinge of uneasiness and held the glance, knowing he had somehow stumbled upon a member of Dusty Bill's gang. One corner of his mind wondered what Buck Duryea would think if he knew the proximity of the outfit.

"So you want to join up, kid?" said the stranger in a slurring, husky voice.

"My intention," said the Kid stoutly.

"Had the idea for some time?"

"Oh, for a matter of months. Had to get a little experience, y'understand. So I held up the stage. Nothin' to it."

"Sometimes not," mused the stranger, more definitely smiling. "Think you can do this Dusty Bill some good by joinin' him, huh?"

"Listen," admonished the Kid, "I can ride anything that's got hair, drill the carnation out of a milk can at ninety feet, track like an Indian. I'm not dumb. I've had experience."

"Ever see Dusty Bill?" drawled the stranger.

"No, but I will," stated the Kid. "When I make up my mind to do a thing, I don't let go. I ain't a man to monkey with."

"As I observe," said the stranger softly. "Well, boy, you've got your wish and you've plumb arrived at your destination. I'm Dusty Bill."

The River Red Kid's eyes widened, and his stare grew pronounced. Unconsciously, a trace of disappointment appeared, and Dusty Bill, never a man to miss the quick changes of expression on faces opposed to him, caught it.

"Well?" he challenged.

"I thought you was bigger," blurted out the Kid, and could have bitten off his tongue.

But Dusty Bill grinned, a peculiarly unsentimental and heatless grin. "They make outlaws small these days, kid. Like you, for instance. Can't pack a lot of weight around in this game. Think you could do me good, huh?"

"I'm not a man to monkey with," declared the Kid. "In some things I'm right smart. I found you, didn't I? Who else could have done that?"

"Ever kill a man?"

"No-o," admitted the Kid, and for once his air of worldly tolerance fell from him. He had never killed a man. That was the weak point in his armor, and he hoped, in a spasm of half fright, that Dusty Bill wouldn't pursue the thought. There was a still deeper humiliation to bear—he didn't like to kill and his toes curled at the very thought of it. But Dusty Bill cleared his throat and spoke with a change of tone. "All right, I'll take you on."

"Yeah...you will?" cried the Kid. "By gosh, that's swell!" Then he pulled himself back to the properly non-committal attitude of a hard man. "We'll get along all right," he finished.

"Now here's my chore for you," proceeded Dusty Bill. "Go back to San Juan. Stay there till I want you. Keep your eyes open, and see what the sheriff does, but don't leave town. I'm depending on you, understand? Even if a stray cat crosses the street, you make a note of it. You'll be my agent in town, clear?"

"Count on me," said the Kid, stiffening his spine. "But how'll I get in touch with you?"

"Leave that to me," replied Dusty Bill. "Get goin' now. And, by the way, I think you better kill a man before I see you again. That'll assure me of your intentions."

He put out his hand, and the Kid took it, to discover instantly that this small, whip-like man had muscles made of woven wire. The pressure of that grip bit into his fingers and numbed them, and a cold, creeping feeling went through his body. At the first opportunity the Kid pulled his hand away and stood a moment, uncertain and touched with an actual dread. The lamplight illumined Dusty Bill's face, a face that suddenly was wolfish in its cruelty; the smile was only a thin pressure of lips. The apparent friendliness of Dusty Bill's eyes had become but a freakish result of coloring, and the dead, flat stare continuing through the strained moments took on the venomous, glass-bright quality of a reptile.

"Get goin', kid," breathed Dusty Bill.

"Yeah, see you later," muttered the Kid and stumbled out the door, glad to be in the open again. His breath came small and fast, and he put the spurs into his pony, prompted by an impulse he could not at the moment fight away from. Leaving the clearing, he rose along a gentle grade, turned the face of a butte, and lost the lights of the house; as he did so, he seemed to fall apart. His throat hurt, and there was an ache in his lungs. Breathing deep of the crisp night air, he became aware of the freedom about him and the cheerful light of the full moon above. It was mighty pleasant to be securely in the saddle and riding again.

"But to kill a man," he muttered. "Good gosh, how'm I goin' to do that? That's... why, that's murder!"

A full mile along the ridge he heard the advance of a rider still unseen, and he promptly put himself off the trail and in the shelter of rocks. The rider came on at a steady gait, passed abreast, and disappeared in the direction of Dusty Bill's hideout. After a long wait, the River Red Kid regained the road and settled to a full gallop, fresh wonder in his mind. The moon had touched that man's face briefly and betrayed it. It was one of Buck Duryea's deputies and the name, if he remembered the saloon talk right, was Lon Young.

"What's he doin' with Dusty Bill?" pondered the Kid. "Great Smokes, he ain't double-crossin' Buck Duryea?"

After repeating the first few lines of the song

about little Annie Lee, Lon Young passed into the bowl and

dismounted at the house porch. Entering, he found not only Dusty

Bill, but Teeter Fink and the other four who constituted the

gang. All of them were lounged about a table, drinking.

"Early," said Dusty Bill. "Meet the kid?"

"What kid?"

Dusty Bill grinned. "He must be good. Evidently faded right from sight. Why, a little, long-nosed, agate-eyed babe who tried to join me. I give him credit for nerve. Said he'd held up the stage."

"Never saw him," said Young, and showed sudden worry. "Wonder if he camped out and saw me come here. Judas Priest, Dusty, why did you let him go?"

"Aw, he's harmless. I told him he was a member and to go back and watch San Juan. You'll probably see him posted around town when you get back, lookin' wise as a bench full of judges. Takes life pretty serious."

But the deputy shook his head and in this was supported by Teeter Fink who spoke doubtfully. "Never should have let him go, Dusty. Bad business. Can't tell what a whelp like that will do. If he's got brass enough to sugar his way in here, he's got brass enough to betray you. Remember, there's a round total of thirty thousand dollars on the heads of you five men."

"Betray?" replied Dusty Bill. "What'll he betray? I'm here, but I'll be gone in an hour, and nobody's fast enough to find me. What's on Buck Duryea's mind, Lon?"

The deputy said: "He doesn't think you're this close, Dusty. He ain't got any idea you're within fifty miles. He's playin' a waitin' game and followin' all rumors."

Dusty Bill's thin mouth twisted. "That's fine. We'll give him another rumor to follow. Lon, you go back, and in the mornin' whisper to him that you've got it on good authority I'm passin' out of the hills and will strike Fort Smith in the middle of the afternoon. That will get him and his posse out of San Juan for a while."

"Then what?" asked the deputy.

"Then, when he gets to Fort Smith, we won't be there," grinned Dusty Bill. "But by dark of tomorrow Mister Buck Duryea, who was sworn to office on the single promise of gettin' me, will be dead and so will the bright boys followin' him. As for you, Lon, you ride to Fort Smith with him and also ride back to San Juan with him."

"Where you goin' to frame this play?"

"I'll take care of that," replied the outlaw.

The deputy showed a trace of nervousness. "Yeah, but how about me? If you're goin' to ambush him, how about me right in the middle of that party?"

Dusty Bill rose and pulled up his belt. "What you don't know won't hurt you, Lon. But you're safe. If it'll satisfy you any, do this...when you come back from San Juan with Buck's party, lag behind a little bit and go to the saloon for a drink."

"You're goin' to...?"

"I'm goin' to catch him where he wouldn't dream I'd be," interrupted Dusty Bill, the words crawling out of his throat. "I'm goin' to put a bullet in the back of his skull as warnin' to this county that nobody's big enough to dog my heels. I've said I'd leave him dead in the dust, and I will. Come on, boys, we've dallied here long enough."

STANDING in the bright sunshine of another hot San Juan morning, Sheriff Buck Duryea listened carefully to his chief deputy's tale.

"I've got this thing straight," said Lon Young earnestly. "Last night I had an idea in my bonnet. So I rode to the east. There's a Mexican farmer over yonder whose name I can't mention. He's a solid friend of mine. He said one of Dusty's men rode in for somethin' to eat...Baldy Zantis, it was. Zantis was out on scout, and he knew this Mexican pretty well. Sort of friendly to him, and in the course of the talk he let somethin' drop about the bunch bein' in Fort Smith today around noon. Then Zantis rode off. The Mexican told me in strict confidence."

"Sounds odd," observed the sheriff, "that Zantis would tell the Mexican and still more odd that the Mexican would tell you."

"Didn't I say the Mexican and Zantis were friends?" queried Lon Young. "And you know Dusty Bill's gang is ace high with 'most all Mexicans around here. He's been good to 'em. None of that race has ever given Dusty away yet. In this case, I did a favor for this Mex once and that's why he told me."

The sheriff studied the distance with half-closed eyes. "What's in Fort Smith?"

"A bank."

"Possible."

"Or, if not that," added Lon Young, "maybe he's making a shift of location and wants to stock up on grub."

"Also possible," agreed Buck Duryea. "Sounds fishy to me."

"You want rumors. Here's one for you," was the deputy's next remark, colder and more impatient.

"That's all it is," said Duryea. "But we'll act on it. Get the boys rounded up, will you?"

Lon Young ambled away. The sheriff walked into the stable, saddled his pony, and led it around to the office. As he did so, his thoughts were interrupted by sight of the River Red Kid, strolling down from the direction of Magoon's. In itself, the act meant nothing. But the Kid carried himself with an air of suppressed importance. There was a slight swagger in his walk, and his eyes kept roving restlessly from one part of the town to the other. At the saloon door, he cast away his cigarette, stared a long while at some object beyond the limit of the street, and passed inside.

Buck Duryea considered all this gravely. Acts like he's got a bug in his bonnet. Damn' little fool. He never came in from the east trail yesterday, either. Sure as apples are green he held up that stage. Give himself plumb away with his talk about experience. Just another kid considerin' the glory of an outlaw's life...led on prob'ly by all the lyin' tales he's heard about Dusty Bill. There's the rotten part about outlawry. It influences kids to do the same...it turns the heads of good citizens. Wish I could do something with that boy. He's got the makin's of a man.

Suddenly the sheriff, moved by one of those kindly impulses that so frequently possessed him, walked across the street and entered the saloon. As he approached the bar, he found the Kid taking a drink.

"Nice momin'," said the sheriff, reaching for a cigar.

"Yeah," agreed the Kid. The blue eyes met the sheriff's gray glance and slid away. As young as he was, Buck Duryea could read a man's face, and he saw something like confusion on the countenance of the boy. And, as he observed this, he felt a deeper certainty of the boy's intrinsic worth. Hard or worthless characters never knew the stirrings of conscience. "Have a drink?" urged the Kid.

"Thanks, no," said the sheriff, and spoke as if he were addressing an equal. "I've got some business on tap, and it won't do to get blurred up with whiskey."

The Kid nodded and started for the door. The sheriff moved out to the porch with him and halted to touch off his cigar. Casually enough, he asked a question.

"Had any experience on the trail?"

"Some," said the Kid. "I can read sign. An Apache taught me."

"That's fine," approved the sheriff. His tone grew more confidential. "I'm mighty glad to hear it. If you stay around San Juan, I'll be using you in my posse. It's a tough country, and I'm always needin' good, stout men, like you."

"Me?" said the Kid, showing astonishment.

"That's right," agreed Buck Duryea. "I don't often make a mistake in judgment." He paused for a moment to let the phrase sink in. Cigar smoke curled about his calm face. "You see," he went on, in the same level, fraternizing manner, "it takes a tougher, harder, stiffer specimen of a man to keep the law than to break it. Ever think of that? Consider it. Any fool can go out and push over a stage or steal a few cows. Nothing to it. But to be honest and fight off the crooks...there's where the test of a fellow's nerve comes in. Next time I ride, I'll be swearin' you in, too."

The Kid said nothing. He held his cigarette tightly between his fingers and stared at the sheriff with a long, wondering glance. The members of the posse had collected at the stable and now came riding forward. Buck Duryea left the porch and started across to reach his horse. Halting and turning, he threw a casual afterthought back to the youth. "Ever notice our graveyard? There's a line down the middle of it. Decent folks to one side, crooks to the other. You'll observe the honest folks have tombstones to mark their memories. The crooks have nothin' but a board headpiece that soon enough will rot into the growin' weeds. A crook's a fool to play the easy game, for it always ends up the same way. Well, see you later."

The River Red Kid watched the posse go, his attention riveted on the tall and easy figure of the sheriff leading off; and, as long as Buck Duryea remained in sight, the Kid never stirred from his place on the porch. But when the curve of the trail swallowed the outfit, the Kid threw away his cigarette and ambled along as far as a bench in front of the saddle shop. Here he sat down.

Not a bad gent, he admitted to himself. Nossir, he talks to a fella like he meant it. I could like a guy like that. Ain't I in a funny fix now?

The street moved with men and women bound on their various chores, and it occurred to him he was not obeying Dusty Bill's injunction to keep a sharp eye on all that transpired. Tipping his hat farther forward against the sun, he watched the scene unroll. A wagon came in; the stage departed; noon arrived; and, as he rose, strangely suspended between happiness and uneasiness, the Mexican girl, Donna, walked gracefully from a far house and came directly toward him. The Kid whipped off his hat, a flush of color staining his cheeks a deeper shade.

"Señor," said Donna, "you will have dinner with us? Come."

"Me?" said the Kid. "Me?"

"Of a truth," agreed the girl and beckoned. The Kid, feeling the eyes of the world upon him, stepped awkwardly beside her and followed her into the house. Down a semi-dark hall he saw the other woman waiting—that one who had been with the Mexican girl on the stage. Not knowing just how it was all managed, he presently found himself sitting at a table with these two.

"It was nice of you to come," said the tall woman.

"Ma'am, that's a generous statement, but the truth is nowise in it. Folks like you are sure kind to endure a fellow like me. Why, I never sat at a table with a white cloth on it in my life."

"Señor," said Donna, sitting very prim across from him, "what is a tablecloth? You save my life."

"Shucks," muttered the Kid, and for the moment was utterly at a loss. But the small services of the meal saved the day for him, and the tall, serene lady spoke pleasantly of things the Kid only half heard. Before he quite realized it, the dinner was done, and he stood again at the door. And the Mexican girl's eyes, round and glowing, were looking up at him.

"Señor, there is a dance tomorrow night."

"Would you go with a fellow like me?"

"With all my heart," said Donna.

"By thunder, I'll be here!" exclaimed the Kid, and walked down the street in a haze of wonder. In the saloon he found the hands of the clock at two. It seemed incredible. Returning to the street again, he sat on the edge of the porch and marveled. And I ate too much, that's what I did! Never missed a thing they passed me. And I talked. What'd I talk about? Lord, I wish I recalled. I bet I told 'em about my life since I was a pup of four. Lord, what kind of a fellow am I, anyhow? But they was kind...mighty kind to me that ain't known such a thing. Never knew folks was like that.

Critically, he surveyed himself in the light of tomorrow's dance. He needed better clothes and a coat that wasn't so full of wrinkles, and, as his hand ran along the coat, it suddenly stopped at the bulge made by the packet of securities hidden within the pocket. On the instant, the feeling of pride went out of him.

I knew I'd wake and find it a pipe dream, he thought. The bright flare of enthusiasm died from his eyes, and, humped against the porch pillar, he battled with reflections that jeered at him, accused him. So he sat, while the droning afternoon went along, and the sun fell into the west. When he at last roused himself from the spell, San Juan was astir, and the supper triangle was ringing in front of the restaurant.

Well, grunted the kid to himself, what'm I goin' to do? Can't be two things at once. Can't dance with a nice girl and be in the wild bunch, too. A pair of riders drew in from the hills and that reminded the kid of Sheriff Buck Duryea—and the sheriff's words exploded in his mind, at last significant. "Easy to hold up a stage," that's what he'd said. But hard to go right. How in thunder could a fellow like me, what never was an outlaw, know about such things? Well, I guess I'm cooked. Better ride from town and forget it.

Automatically, he turned to the hotel and went over for supper. As he tackled his soup, he was deeply submerged in melancholy, but, when he had reached his pie, the normal optimism of youth had reasserted itself, and out of that optimism came an idea that sent him to the street with his blue eyes sharply bright again. It was going on dusk, and over San Juan lay a stillness and the smell of dust and sage. Pausing on the hotel porch, he built a cigarette and calculated his chances. Nobody knows I held up that stage. Now, look. Here's this package in my pocket. Supposin' I get it back to the bank. That clears me. I won't steal no more. Nobody knows...except Dusty Bill, and his word don't count.

The bank, he observed, was down toward Magoon's store, on the hill side of town. Doubtless there was a window he could break and through which he could pitch the packet of securities. And here was dark, deepening over and through the town like layers of soft, felt cloth. Of a sudden, lights sprang out of buildings and from the saloon came the twang of a guitar. The River Red Kid threw away his cigarette, mind made up. I'll have to play it square. Can't go on any of the sheriff's posses and chase Dusty Bill. Wouldn't be right. But I can mind my own business and be honest.

With the decision quite crystallized, all things seemed brighter. The very air had a wine-like vigor in it, and immediately a vast impatience possessed him to make restitution. By now the shadows of the porch had completely absorbed him. Men tramped along the boardwalk, murmuring amongst themselves, cigar tips creating points of light. The Kid waited another moment, then lifted himself over the porch and railing, and faded down an alley between buildings to the rear of town. Treading lightly, he passed the full length of San Juan, turned a corner, and flanked Magoon's store. This brought him to the hill side; and with infinite caution he crept as far as the side of the bank structure and waited.

There was a window, out of which gleamed a dismal, crosshatched lamp glow. Adjoining it was a door. On the point of pressing in the glass of the window he conceived the idea of trying the door. It was, of course, locked, but his exploring hands ran along the bottom and found a small crevice. This was much better business than breaking glass and risking discovery; so he took the packet from his pocket, ripped it apart, and fed the individual slips of paper through the crevice.

When he stood up, he sighed profoundly, like one who had held a long, accumulating breath. It don't make me exactly honest yet, he reflected candidly, but, by thunder, it's a beginnin'. Now I better get out of here before I'm found.

Instead of retracing his path, he elected to sidle forward and come into the street at the open end, thus making a circle.

Onward, a distance of fifty yards—the bright moon aiding him considerably—he came to a gap in the building line. At this point he stood directly behind the saloon. Beyond that was an open area, closed off from the street by a high wall, and at the far side of the area another building terminated San Juan's southern row of structures. This open space seemed to be a kind of town pasturage, for in it was a straw stack, a few abandoned wagons, and a lone horse, grazing. Pausing there, he suddenly fell on his stomach. A man moved out of the hills on a dead run and gained the shelter of the straw stack; a moment later he left the straw stack and placed himself against the boards. As he did so, the Kid's wide eyes discovered what he had previously missed—four other men hidden against that wall.

His first impulse was to retreat. Before he could move around, one of the men seemed to grow restless and backed away from the wall. Advancing toward the saloon's rear, he came within fifty feet of the Kid, stopped, turned, and started back. The Kid's muscles suddenly turned to layers of ice, for the moonlight had revealed the pointed, set cheeks of Dusty Bill.

Dusty Bill was against the wall again. The Kid, taking this advantage, crawfished a full forty feet along the saloon's end, reached an opening between buildings, and rose to scuttle down it, thus coming to the street again. One glance reassured him, and he stepped on the walk.

He's in town. Him and his gang. Some hell's about to bust loose, and I'm supposed to be in it. By thunder, I'm ridin' out!

His horse was in the stable, and that way he turned, moving across the street. By now his senses were on the race, and all the sights and sounds of San Juan fed through him in a constant stream. Exactly in the middle of the street he halted and swung about, facing to the east. Out there on the margin of town was the distinct crunch of a cavalcade coming on; and, as he heard it, the whole forthcoming scene became clear and cold and terrifying in his mind. That was Buck Duryea returning. Buck would pass the board fence and become a target. Buck would die—that was the meaning of Dusty Bill's being in San Juan tonight. Even then, he saw the sheriff appear from the shadows, riding away and unconcerned at the head of the posse, and only a few yards from the fence.

In that terrific, racking interval, the River Red Kid became what he was ever afterward to be. And in that interval the volcanic force of warring loyalties was not in his heart. He was proud of his word because he knew a man had no greater possession—and his word had been given to Dusty Bill. Yet, even as he felt the force of it, the calm and kindly figure of Buck Duryea strengthened before him. For, after all, at sixteen the Kid was still a worshipper of heroes, and through the strange irony of events Duryea had become that to him Duryea, the man of the law whose few words and quiet sympathy had performed this alchemy. The Kid had not wanted it so in the beginning; he had sought out Dusty Bill with the glamour of Dusty's name moving him. But it was given to a greater man than Dusty surely and inevitably to make a follower of this youth.

All this was but a brief moment's transaction in the Kid's mind. The battle had been waged and won without his conscious will; and the decision made equably without deliberation. The Kid responded to the strongest pull. Reaching for his gun, he broke into a shambling run down the street, abreast the board fence, straight toward Buck Duryea.

"Watch out...a trap...Dusty...behind that fence...!"

That was all. There was a roar and a crashing as of the heavens falling in. The Kid staggered, spun backward, and fell to the dust. But from his position he saw Buck Duryea, straight and sure in the saddle, charging the board fence and the posse spreading beside him. A single rider broke out of the posse and galloped toward the saloon—Lon Young, crying at the top of his voice: "Me...me...Dusty!" And then above the fury his cry rose to a scream, and he pitched from the saddle, whirling over and over on the street.

There was a splintering and ripping of boards. The posse jammed against it; horses pitched wildly and tried to fight closer. But Buck Duryea, towering above the fence, was slanting his fire downward, ever downward while the purple-crimson muzzle light flickered through the shadows. Another member of the posse drew off, plunged his horse into the fence, and broke one of the sustaining posts; the line of boards sagged, and the concerted rush of the sheriff's party did the rest. Dust rose in heavy eddies around the River Red Kid, and he heard, through his pain, the echo of firing diminish and presently die. After the whirlpool of conflict was an overwhelming stillness, broken only by the rush of horses, breathing hard, and the low mutter of the possemen beyond the broken fence. Then, as swiftly as the street had cleared, it filled again, and San Juan raced toward the scene.

The Kid heard broken phrases all around him.

"That's the end of Dusty..."

"Never was a fight like this in the history of the country!"

"Duryea, you kept your promise!"

The Kid felt a hand on his shoulder. Buck Duryea dropped beside him, straight and deep lines across his forehead. "They get you, Kid? Where?"

"It ain't fatal," mumbled the Kid. "Somewhere up along my shoulder. It just hurts, that's all."

"Old-timer," said Buck Duryea, a queer set to his cheeks, "you'll be my right hand man when you get well."

"Listen," said the Kid, "I ain't what yuh think..."

"Shut up," said Buck Duryea. "Dusty's dead and so are the rest of his gang. He was the one that held up the stage, Kid. He was the one."

"Yuh'd do that for me?" groaned the Kid.

"Better to make one good citizen than an outlaw," said Buck Duryea softly. "You've got everything a good man needs, my boy."

"Hell," said the Kid. "It ain't goin' to be so hard as I thought. Sheriff, don't you never worry about me no more."

There was a swirl of skirts near him and a small hand pressing against his head. Donna Chavez's agitated question was like a shock. "Señor Buck, is he hurt?"

"Not too bad," said the sheriff. "I'll carry him to the house. You can take care of him, Donna. Better do it well. He's my right hand man now."

"Me!" cried Donna. "I will take care of him. For a long time!"

"Can you imagine," muttered the youth and ground his teeth together when Buck Duryea lifted him from the ground. But above the patio was the exultation of a risen spirit, the blaze of a tremendous emotion. Me... a no-account like me? By thunder, I won't make liars outta fine folks! Never, never in this world!