RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

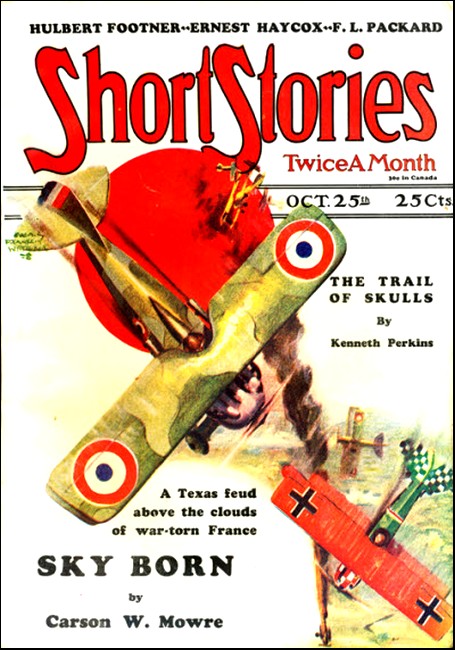

Short Stories, 25 October 1928, with "Fandango"

An hour before the sheriff of Sam Pearce county was to be married it was

a good hundred to one bet that, alive, he'd never get as far as the altar.

WHEN Will Drum, sheriff of Sam Pearce County, stepped from the

hotel this hot summer's morning to face the somnolent dusty

street and the battered buildings, it was with the knowledge that

the day marked a definite turning point in his life, that between

dawn and dark the old trail he had traveled for so long a time

would meet another trail. And down the widened highway he must

go. Will Drum was young, and hitherto he had accepted his share

of living with the mingled gravity and good-humored fatalism so

much a part of him. Today was different and, as if to accent the

fact, he had laid aside the faded dusty clothes habitually worn

in favor of the full panoply of the Sunday dressed man.

A new broadcloth suit draped his rangy frame, a white shirt and string tie covered his broad chest; the old boots were gone in favor of a pair freshly stamped, freshly polished; the lopsided hat that had served him for many a year in the manifold capacity of ear muff, umbrella, water bucket and fire-fanner was likewise abandoned for a cream yellow Stetson with a stiff brim. Thus he faced the day, a bronzed, blue eyed man good to look upon, attired in a two hundred dollar outfit. Between sun-up and starlight Will Drum was to be married.

Therefore the new clothes. But there was one item about the young sheriff that remained unchanged. Beneath his coat and failing below his right hip rested the weight of the forty-four he had carried since his father passed it on to him. This solitary piece of old apparel, almost as much a part of him as his five senses, he had strapped to him in the full knowledge that his wedding day would also bring him face to face with the most dangerous crisis of his career. Between sun-up and starlight they had marked Will Drum for death.

Will Drum was only twenty-six, but as he rolled a cigarette with those long and tapering fingers and as he touched the match to the finished product he swept the almost deserted town with a hard, flashing glance and his gray-blue eyes seemed to demand an accounting of each alleyway and each deserted door and each open window; he was weighing the street for the possibilities of evil and the result settled his lips in a thin line and sharpened every feature. At twenty-six and on his marriage morning Will Drum should have been rollicking and reckless, for the past record of his life was one of exuberance and of heady disregard for property and persons. Humor slept uneasily on his face, humor lay in the fine wrinkles between temple and eye socket. Yet Will Drum had been sheriff of Sam Pearce for ten months and it had aged - him ten years.

Sam Pearce was a county of factions; under the drowsy, slow- moving surface were hidden swift and vicious tide rips of intrigue. No sheriff of Sam Pearce in thirteen years had served out a full term; and today the word had gone out that Will Drum must go the way that many of his predecessors had gone. The ultimatum was in the air, it had passed along from place to place, touching everybody; as intangible as the scent of sage in the prairie, yet equally certain. Will Drum was to die.

HE moved down the deserted street in long and lazy strides,

spurs jingling, the sun slanting into his boldly carved features.

He passed his office and tarried at the stable.

"Put the two bays on that new rig, Charley," said he to the roustabout. "I'll be goin' out in half an hour."

The roustabout leaned on his pitchfork, grinning. "Today's the day, uh, Will?"

"Today's the day," agreed Will Drum, and for a moment the natural buoyancy of the man flickered through the set gravity of the features, like the fitful explosion of a damped fire.

"Knew yuh'd want that outfit," said the roustabout. "I curried 'em an' I braided their tails. An' the rig's polished enough fer the lady to see her face in it. It's a big day, shore enough. The county's movin' into town total. They's eight Mex guitar players—" Here the roustabout halted his tongue. "Reckon I hadn't: better spill the beans. The boys'd skelp me alive." He studied the sheriff at length and in time the grin faded before a narrow-eyed worry. "Yeah," he muttered, "but—"

"In a half hour, Charley," said Will Drum and turned back. He walked leisurely toward the building that served as office and jail for the county. Across the narrow street the swampers were opening up and sweeping out Sam Horrell's Palace; through the door Will Drum saw the stacked chairs and the mahogany bar—and saw Sam Horrell moving around that bar, taking stock. Will Drum's lips pressed more tightly together. He went into his office and found Hackamore Weaver, his deputy idling in a chair.

Hackamore was a short man, built like a bulldog. He had red hair and he was a fighter, when he had to fight or when he was given orders to fight. Otherwise he liked to stay in the background, and he seldom spoke. He didn't speak now, but his eyes followed Will Drum around the room, measured the sheriff up and down the broadcloth suit and presently came to rest upon the tip of the gun holster showing beneath the latter's coat. Weaver was an invaluable subordinate. He had an uncanny eye for details and an extraordinary ability for discovering things without asking questions. Because of his retiring disposition Sam Pearce County underestimated him, but Will Drum knew better.

The young sheriff settled himself against a wall and rolled another cigarette, returning Hackamore Weaver's glance. The two of them understood each other very well and their minds ran along the same groove at the present moment. Drum lit his cigarette.

"Find out anything definite, Hackamore?"

Hackamore shook his head, scowling in a manner that brought his scalp line down toward the bridge of his nose. "Nobody's talkin' this time, Will. Tracy an' the Horrells shore have put the fear o' God in their gang. Nobody's murmurin' a syllable."

"Well, I'm ridin' out in the rig. Be back around noon."

Hackamore stirred. "Wish yuh'd lemme ride along, Will. Yuh got to pass the Point o' Rocks, an' yuh got to pass the Horrell ranch."

DRUM shook his head. "It won't be at either place, Hackamore.

They aim to make a grandstand play of it. When the hammer falls

it'll be in town when the crowd is lookin' on. They want to make

a public example, want to show the county who's boss. Get the

idea, Hackamore? A public sacrifice. Due warnin' of ownership I

guess you'd say."

"They'll be a crowd in town," said Hackamore Weaver. "I heard about every outfit within twenty miles is ridin'. Yuh got friends in Sam Pearce, Will. The boys aim to make it the biggest fandango ever throwed. 'Tain't only that, either. The hint is sorter scattered about gunplay. Funny how such things travel. Well, it'll be merry hell an' don't yuh misdoubt that none. Yuh got friends in Sam Pearce. When the first aimed shot is—"

Will Drum checked his deputy with a swift gesture. "Listen, Hackamore. This ain't a day for war. We've got to postpone trouble somehow till tomorrow. No blood spilled on my weddin' day."

"It's comin', nev'less," muttered Hackamore. "How or where I dunno, but it's comin' and we can't stop it."

Will Drum threw away his cigarette. Anger gleamed in his eyes, erasing the latent pleasantry, chiseling hard lines along his jaws. It made of him a gray and unforgiving man. Seen in this mood he was the picture of some thin-blooded and conscienceless figure come to town—like one of the Horrell gang. "Damn their souls, they've got to leave me alone at a time like this. Personal, I don't care. They can try all the tricks on me they want, they can lay their traps and follow my trails. It's a part of the game. But they got to keep their dirty paws off Kit Lovelace. A woman likes to remember her weddin' day. It's somethin' she looks back on no matter how long she lives. Won't have Kit's marriage ceremony marked by blood. Hackamore, by thunder, I won't!"

"It's comin'," repeated Hackamore.

Will Drum stared through the door and at the sun splashed street. "I ain't been too hard on the Horrells and their gang. I've scotched some of their dirty work, but I reckon they've had an even break. I could go a lot farther with them and still be some short of plain justice. But the county don't want a hundred per cent justice, Hackamore. Never did, don't now. Folks like a sheriff to hold an easy rein. Even the strictest gent in Sam Pearce wants it that way. Some things I got to wink at because the county wants 'em winked at. It's human nature and the sheriff that can't read the signs ought to turn in his star. But they've got to leave me alone today. I'm not pullin' my gun. Not any time from now to midnight."

Hackamore dissented sharply. "Now don't make up yore mind too strong on that point, Will. You'll regret it."

"No gunplay today," insisted Will Drum. "If they make me break that rule, I'll go back to the wild bunch and make the Horrells wish they were dead. Well, I'm travelin'. Stick around and see what you can pick up, Hackamore."

Hackamore nodded, watching Will Drum turn down the street. The deputy's bulldog face set stubbornly. "He'll keep that rule. It's the way Will's made. An' they'll shoot him cold. I wish I knowed which way the wind blew."

IT was not by accident that Will Drum crossed the street and

leisurely walked in front of Sam Horrell's Palace; nor was it

accident that brought Sam Horrell to the door as the sheriff came

abreast. It seemed accidental only because the dominating figures

of Sam Pearce cloaked their purpose behind casual words and lazy

motions. Will Drum nodded his head with a polite gravity; Sam

Horrell raised an arm, equally grave and polite.

"I reckon it's an important day to you, Will. Come in an' give me the pleasure o' bein' the first to wish you a lifetime's happiness."

"I believe I will. After you, Sam."

The two of them strolled across the shaded room. An immense place it was, with a stage at one end and a bar that formed an ell on two sides. Crystal chandeliers broke the ceiling, oil paintings of stage beauties and prize fighters marched along the wall with here and there an elk head or a war bonnet or an ox yoke. Sam Horrell's Palace was no ordinary saloon. The man's pride was in his establishment and at night when the lights gleamed down upon the mahogany and the chorus sang from the stage the Palace mirrored a luxury far above the level of Sam Pearce County. Horrell went behind the bar and set out a bottle. And then, as if he understood what was in Will Drum's head, he set out a decanter of plain water.

Will Drum took the water, for this was' his wedding day.

"Luck," said Horrell, matching his glass against Will Drum's; and they drank.

Sam Horrell had come out of Texas thirty years before, riding a horse, Indian style— bare back and with a length of rope for a bridle; too impoverished even to own saddle gear. And all that he wore was butternut jeans and a cotton shirt. At forty- five he was rich in goods. The Palace was but a plaything; Sam Pearce didn't know just how many acres he ranged or how many cattle were thereon. And this Horrell's word was law to a great many people.

He was a burly man, with a skin almost olive in color and a poker face; he had a marvelous command of his tongue and his temper. He smiled easily, but the smile came only at his bidding, and vanished soon. He mocked at his early poverty now; his clothes were the finest he could buy, he wore two watches, carried a three-thousand-dollar diamond loose in his pocket and had a trick of wiping his boots with silk handkerchiefs. All of this was outward show and fooled nobody. Sam Horrell was as cold as ice and had a lust for power; the role he loved was that of a desert Warwick.

"You're a lucky man," said Horrell, dropping his glass. "I mean that."

"I reckon I realize it, Sam," drawled Will Drum. They were watching each other, they were sparring. Will Drum's blue eyes probed into Horrell, trying to lift the enigmatic screen stretched across the intensely black orbs. Horrell took pride in his ability to baffle others; usually he smiled and turned them off with phrases, but Will Drum threw him back to a colder, more cautious expression.

"What I mean," went on Horrell, "is that single rig is all right for young bloods. But when a gent gets along in years he sorter misses somethin' and then it's too late to buck the market. The lady in question, Will, is worth fightin' for. No better girl ever was raised in Sam Pearce."

"I reckon I realize that too," said Will Drum quietly.

HORRELL took a pencil from his pocket and began to create a

series of flourishes on the stock list in front of him. Here was

another point of vanity with the man. He had taught himself to

read and to write after forty and he loved to make a parade of

his Spencerian hand. It had come to be a habit with Horrell;

whenever he talked he reached for pencil and paper, writing words

or phrases or drawing geometric figures—none of which ever

had a bearing on his conversation. It was something he never gave

a thought to; it was automatic with him.

"Ever figger," said Horrell, "that the sheriff business ain't very stable or prof'table for a married man, Will? After today the risks you take don't only concern you. The wife has got to be thought about."

"When the county gets tired of me, Sam, I'll move on to my section."

"Providin' some wild gent don't get careless with firearms before said time."

Will Drum nodded. Horrell dropped his head and took to tracing a set of letters over and over again on paper. He put flourishes on them, encased them in a corral, drew lines leading away to lesser corrals— and inside these placed the same letters. He seemed engrossed in this business but Will Drum knew the man's thoughts were elsewhere.

"I'll take my risks on that, Sam," said the young sheriff, watching Horrell's turning pencil point. "It's in the game. But not today. Today is time out. I'd hate to see trouble between now and dark. Hate to think of anything happenin' which'd hurt Kit. Reckon you see that, don't you, Sam?" The pencil stopped. Horrell raised his head, the eyes wary. "That's a natural sentiment, Will. Today ought to be a fiesta, nothin' else."

The sheriff's eyes passed across the paper. In the semi- darkness he seemed to grow taller. When he spoke the words broke the quietness with a kind of staccato explosion. "Fact is, if it did happen, Sam, I wouldn't forget. Somebody would suffer, and said somebody's uncles, cousins, nephews an' companions would also suffer. That's the way I feel about it."

He had worked for the appropriate opening and he had put across his warning. So he turned and walked to the door. There he tarried a moment to adjust his eyes to the sun. Horrell's voice echoed dismally across the great room. "Nothin'll happen, Will. Not today."

"Glad you think so, Sam," said Will, and went on across to the stable. He had turned an instant to see Horrell's head bent over the traveling pencil, making hen tracks again. Getting into the buggy he drove out of town, along the road that ran due west toward the Lovelace Broken Stirrup range.

The day was hot and clear, and the leagues of land ran straight into the horizons. He passed Three, Five and Seven-Mile Creek, the team laying the prairie behind them at an even, unhurried pace. Point of Rocks bore down—volcanic slabs rearing skyward and the trail passing through a channel. Hackamore had warned him about the Point of Rocks, but Will let the horses run. It wouldn't be here. When the trigger fell it would be in town, for all the county to see and take note. So he left the Point of Rocks to his rear and struck a due course for the Horrell main ranch. To the south stretched the deep and thin Apache trail, winding its tortuous course toward and across the border.

THE trail was familiar to Will Drum and he let his mind wander

back to incidents that had happened on it. Mexican renegades used

it often in rustling cattle out of Sam Pearce and running wet

stock into Sam Pearce. This, too, was a part of Horrell's

activity and his ranch was the heart of the wide-flung web. Down

that trail he, Will Drum, had gone not more than four months back

in pursuit. He had crossed the border line, retrieved the stock

and fought it out with Horrell's paid Mexicans. There had been a

diplomatic ruckus raised about his invasion of foreign soil, but

that hadn't harmed him any. Before the event he was only a

youthful sheriff yet to win his spurs. Afterward he was a figure

in Sam Pearce and upon his shoulders fell the burden of such

orderliness as the county wanted, as well as the powerful

antagonism of the factions arrayed against the law. And now the

Horrell gang had him marked, and today was the day.

"Sam said there'd be no shootin'," murmured Will, lids closed against the sun. "But he didn't mean that. He gave himself plumb away. It's in the cards. Well—"

The Horrell ranch stood ahead. Will Drum came upon it, skirting corrals, sheds and house. There was dust in the corrals and men working there. They saw him and recognized him but, save for one man, no raised hand gave him a greeting. The exception was a lithe, wasp-like fellow who strode away from the bars, arresting Will's progress with a gesture. The sheriff reined in.

"Howdy, Will. Today's the day, uh?"

"That's right, Arizona."

Arizona Tracy was jef of the Horrell outfit, riding boss of the organization, star gunman. There were many men nearer to Sam Horrell than this one, for the Horrells were a numerous tribe and a formidable truth, but it was to Arizona that Sam turned when he wanted authority and action. Arizona was a skinny man with a skin that burns to beef red yet never tans. He had pale eyes and the curling fine hair of an artist. He was an artist, an artist without nerves, without known fear or remorse. He never smiled.

"We boys'll be in town, Will, for the celebration. Ain't yuh some excited?"

"I reckon."

Arizona studied the sheriff. "Like hell! Yore a cool cucumber. Heard they was to be a fandango with eight Mex guitar pickers."

Will Drum took up the reins. "I guess considerable excitement is scheduled, Arizona."

Arizona digested this. His pale eyes flickered. "It's what I've heard. We'll drink later mebbe, uh, Will?"

"Sometime," said Will Drum very slowly, "after sundown." He rode off, leaving Arizona standing in a study. A quarter mile farther on he spoke to the team. "That's about all the warning I could give Arizona. But he's sharp minded and he'll understand. If they force me today, they'll sleep in boot hill, every damned one of 'em!"

EIGHT miles farther on he entered the yard of the Broken

Stirrup and reined in at the house porch. A trunk, packed and

roped, stood waiting for him, and odd bundles and bags. As he

stepped from the rig Kit Lovelace came slowly through the door,

smiling uncertainly, the light of her eyes flashing like sun

after a rainstorm. Her chin was up, her yellow hair gleamed like

China gold. Back in the house a woman cried.

"I'm ready, Will," said she, the words striking rich melodies. "Mother and dad and the boys are coming later by themselves."

Will Drum took off his hat and looked at her so long and so seriously that the girl laughed. "You have seen me before, Will. You'll see me the rest of your life."

"Which is a comfortin' thought," muttered Will. "I dunno just what I'd do if it wasn't to be thataway." He bent his back to the luggage, stowed it in the rear of the rig. He gave his arm to Kit and helped her to the seat, the blue eyes searching her through and through. But he said nothing more at the time, for this was the girl's leave taking from a roof that had sheltered her since birth, and he understood. He gathered the reins and circled the yard, going back along the road to town.

Kit Lovelace looked around once as they cleared the gate. Will Drum watched the horizon studiously, but he felt her stiffen and from the corner of his vision he saw her two hands closing tightly together. A long time later one of those hands crept through the crook of his elbow and rested there. "I'm not crying, Will."

He turned then. A smile wavered on her dear face, she sat like a soldier, her robust body swaying to the rig's movement. And unaccountably Will Drum felt both shamed and humbled. "Lord, Kit, I guess you've got a right to. When a man pulls stakes from home it don't mean anything to anybody except his ma. But when a girl leaves it cuts hard both ways. Well, it's a tough world, but I'll—"

"You've said all you ever need to say, Will. I know. I know you'll be good."

"You bet," muttered Will Drum laconically. It sounded dry and unsentimental; but his eyes flared like live coals.

"Dad never meant for me to hear," said she some time later, "but he told my brothers there was to be some trouble. Will—are the Horrells after you again?"

"Not today, Kit. It's only talk. Not on our weddin' day."

"What happens, must happen," she said wistfully. "I won't complain. But today I'd like to think was free to us—"

"I'm not liftin' my gun from now to midnight, Kit. There'll be nothin' to bother your head about." And, having given his word, Will Drum meant to keep it. No matter what happened. There was just that much of chivalrous illogic about him—he who had been bred and raised a bitter realist in a land of realists.

Kit Lovelace turned gay. "Don't leave me too young a widow, Will."

"Not unless your biscuits are plumb awful, ma'am."

"I'll bet you're only marrying me to get away from restaurant cooking."

"That's about the size of it," said Will, chuckling. And for the rest of the trip the talk was no more serious than this, though both of them were playing a part. Kit Lovelace knew the land and its intrigues and the feud swirling about the head of this man who was soon to be her husband. The talk of trouble, she understood, was not idle talk, but she had long ago decided that whatever happened she would keep a serene countenance in front of him. As for Will Drum, he drawled on with his grave nonsense while his mind revolved around Sam Horrell and the approaching crisis. It would come this day.

So at noon the rig passed down the town street to the hotel, and Kit was installed in the room that was to be hers until after the wedding.

AS the afternoon went on Sam Pearce County left its chores and

rode into town. The street, normally deserted on this day and

hour, echoed to the beat of many hoofs and the jingle of many

spurs. They came, the men of Sam Pearce, in leisurely parties,

they came in pairs and they came solitary. Some were smiling,

many were quite sober, and presently it was to be observed that

there was a cleavage of ranks. One group held itself aloof from

another group and between them was a constant and veiled

surveillance. The slightly smaller of these groups did its

drinking and moved toward the sheriff's office; the other kept to

Sam Horrell's Palace and as its ranks increased the drawl of

speech rose in volume, the smoke swirled thicker and a tension

touched each man's nerves.

It was to be observed, however, that at about four o'clock Sam Horrell disappeared from sight and with him also vanished the rest of the Horrell tribe and Arizona Tracy. They slipped quietly away from the excitement and each, at a decent interval, dropped through the alleys beside the saloon and entered a door that brought them to Sam Horrell's private office. Sam Horrell sat up to a table, his burly head bent over a sheet of paper upon which his pencil made fancy figures and scrolls. Four other Horrells sat around that table; Arizona Tracy stood in a corner, leaning idly against the wall and smoking a cigarette. Upon the cheeks of the others was a perceptible constriction of excitement, but Arizona's pointed face and pale eyes held no emotion whatever. Once he raised a hand and spread apart his tapering fingers, to inspect them with a cold, half-lidded glance. And during the parley that ensued he said no word; only listened with his head tilted nearer and the tobacco smoke alternately hiding and revealing his eyes.

Sam Horrell came out of his silent reflections with an abrupt snap of his heavy neck and shoulders. "Listen close, boys. Drum gets married at six o'clock. They eat supper. By which time it's gettin' toward evenin'. Then they leave the hotel for the fandango at the lodge hall. When they ride through the street in the buggy—it ain't only but a short walk but it's in the ceremony that they ride—the crowd aims to give 'em a charivari. Natcherally every gun in town'll pop. Right then, when the noise is goin' on and everybody is shootin' the sky full o' holes, a bullet ketches Will Drum under his ribs. He's down, he's through."

ANOTHER of the Horrell clan broke in. "The rig will be

surrounded by his friends, Sam. He's wise enough to keep himself

covered, or if he ain't you bet Hackamore Weaver'll see to it.

How're yuh aimin' to get clear shot through all them riders?"

"By postin' a man up above the crowd," grunted Sam Horrell, and for the moment his attention wandered and the pencil took up its circling again.

"Why beat around the bush about it? Why not come out direct an' make a public play? We got men enough. Here's the time to sweep the country clean."

Horrell stared at his kin coldly. "I'm givin' orders here. I'm boss."

"I was only askin'," muttered the other weakly.

"It ain't my policy to have a general scrap," went on Sam Horrell. "I want Will Drum dropped in the middle of the excitement. Want the town to see him sag, but I don't want 'em to know where the bullet came from. That's the way I work. Ain't you learned it yet?"

"How about the girl? She'll be settin' beside him."

"The bullet's got to be fired from an angle, got to come pretty near head on. The girl's safe enough. Now, he's got friends in town tonight, but unless I'm mistaken they ain't goin' to start a promiscuous row. Not when they don't know who pulled the trigger. It'll throw 'em off guard. Our boys'll be scattered along the street, not doin' anything, not sayin' anything. I want that word passed around. It's hands off for them except Drum's friends open up. If they do open up, then it's a free quarrel and we pitch in. Get that? All right. One man has got to do the killin'. One man in this room."

The four other Horrells looked down at the table. Sam Horrell smiled grimly to see the pinched fixity on their cheeks. He played with them a moment and lifted his eyes to the silent Arizona Tracy in the corner.

"It's you, Arizona."

Arizona nodded, as if he had known this thing all along. The other Horrells relaxed and began to offer suggestions. Sam Horrell checked them with a gesture, speaking to Arizona. "Take yore Remington, Arizona. After the wedding ceremony climb up the back side of the New York hardware store. They's a vacant room in the front—the one Doc Emming used to rent. Pull up the window an' take yore bearings. The rest is up to you. I'll have one o' the boys waitin' behind with a hoss. It's to be done soft an' quick. Hear it? Do yore shootin' when ev'body is raisin' Ned. Hear it?"

Arizona nodded, the lids drooping farther down upon his pale eyes. Sam Horrell looked at him with a hard, triumphant satisfaction and rose from his chair. There were two packages on the table; he picked them up and motioned to the rest of his kinfolk. "Come with me: We're payin' our respects to Will an' Will's girl. It's some presents."

They went through the door into the main hall of the Saloon and out upon the street, with Sam Horrell here and there beckoning to a puncher, so that by the time they arrived at the hotel there was a respectable delegation of the Horrell gang trailing behind the bulky leader. And quite casually others of the opposite party drifted along and draped themselves in the lobby. Will Drum was nowhere to be seen, but his deputy stood idle at the clerk's counter and to him Sam Horrell spoke.

"We got a little ceremony, Hackamore. I'm wishin' yuh'd notify Will an' the lady we'd be pleased to see 'em a minute."

HACKAMORE nodded and cruised up the stairway. Presently he

returned with Will Drum. The latter came across the lobby and as

he walked there was a slow withdrawal of the crowd, leaving a

space behind him and elbow room on each side. Hackamore Weaver

stepped back a pace, seemingly lazy and indifferent.

"The lady," drawled Will Drum, "sends regrets, but she's occupied with other chores."

"Pshaw," said Sam Horrell regretfully. "I reckon then you'll bear to her our best wishes on this matrimonial day. And with said wishes we'd like for you to kindly give her this token of esteem." So speaking he unwrapped the smaller of the packages he bore and held up a cameo pendant for the crowd to see. There was a smile on Sam Horrell's face as he gave it over and for a moment the man seemed handsome. Will Drum accepted the present with unimpeachable courtesy. He bowed. "I will thank you for her. And I don't misdoubt but what she will thank you later."

"And now," went on Horrell, undoing the larger package, "we got a small gift for you. It took us a long time to make up our minds as to what'd be suitable, as to what'd express our sentiments toward one of the most popular officials Sam Pearce ever had. In the end we figgered that since you was a ridin' sheriff and not an office sheriff the best thing would be the most practical thing. We're givin' this with our compliments an' sincere hope that every time you put it on you'll kindly remember the source." The wrapping fell away and a blue broadcloth army overcoat of full skirts unrolled in Horrell's arm. It was an expensive gift, a lasting gift; Will Drum's hand ran across the cloth as he accepted the coat and smiled at Horrell.

"I reckon, Sam," he murmured, "yo're doin' things brown. It's the first time ever I knew I was popular in Sam Pearce."

"We hope," went on Horrell, "that to please our fancy you and the lady will wear said gifts tonight. It would give us pleasure."

"It shall be done, Sam," said Will Drum. The two men studied each other for a spell with a poker gravity and then as if pulled by the same string they bowed. The Horrells went out. Will Drum climbed the stairway with Hackamore Weaver. Up in the hall the deputy stopped with a short protest. "That pendant—it's a blood gift, Will. An' yore coat is a shroud. Yuh aim to wear it?"

"I reckon, Hackamore."

"Know what it means?"

"Let's hear yore idea, Hackamore."

The deputy tapped the coat with his finger. "It's a dodge. Yuh can't pull yore guns with this thing on. That's why they gave it. To hobble yuh. An' the jewelry is a blood gift to Kit. Don't be fooled. Keep yore guns free."

"I'm not usin' 'em tonight, Hackamore. I've said it before."

"Then yuh die!" was Hackamore's sharp protest. "The Horrells an' Arizona Tracy met in the back room of the Palace fifteen minutes ago. I saw 'em sift in. Couldn't hear what they said, though."

WILL DRUM stared down the hallway for several minutes.

"Hackamore, do you reckon you could get into that back room

without bein' seen?"

"I reckon."

"Well, try it. Wait till supper time. If there's anything on the table bring it to me. Anything at all."

Hackamore nodded. "All right. And say—I'm postin' the boys along the street when yuh ride." With that he went on down the stairway and outside.

Six o'clock came and with it a sudden constriction of interest and a swift arousal of excitement. There was a ceaseless tramping of boots up and down the plank walk and an unending progression in and out of the Palace doors. The town's preacher walked hurriedly into the hotel just as the sun fell across the western rim; a puncher inside the lobby presently came out with a message:

"Supper's goin' up now. Be about twenty minutes or mebbe an hour. How'n hell should I know the amount of time? I ain't never et a nuptial meal."

The information went through the street. One of the sheriff's friends raced the length of town and back again. Riders swung up and cantered to the hotel, faced it and sat saddle, elbow to elbow like a row of cavalry guards. The stable man brought the rig around and drew it to the edge of the porch. Dusk came, Sam Horrell's Palace blazed with light and thundered with the sound of men singing to the tune of the chorus. Under the cloak of all this men slid quietly into alley entrances, men tarried at the street-ends and loitered by the lodge hall's open door.

The Mexican guitar players swung into a practice tune; out of the shadows and across the hotel porch walked Hackamore Weaver.

He stopped a moment to study the grouped horsemen and he stepped toward one of them, murmuring softly. The man nodded twice, whereat Hackamore moved inside and up the stairs. A door stood ajar and through it he saw Will Drum and Will Drum's wife surrounded by members of their immediate family. The wedding supper was over, the ceremony complete. Hackamore caught a full view of his chief's face and the sight of it seemed to disturb and anger him. "Damn the critters," he muttered. "Why can't they let Will alone tonight? Ain't he got a minute's peace a-comin'?" Then he knocked softly and stepped back.

Will Drum slid through the door and closed it, cutting off the light. They stood a moment in the semi-darkness, seeming to find words difficult. In the end it was Hackamore who broke the silence with a gruff, embarrassed greeting. "Well, good luck, Will. I dunno any man more deserves it. But—but I reckon things'll be different now some."

"Better, Hackamore. Some day you'll sabe that."

"Well, I slipped into Horrell's office. Nothin' on the table but a scrap o' paper. Nothin' worth while. I brought it, though."

"Let me have it." A match flared in the hall; Will Drum's blue eyes flashed down upon the proffered sheet and rested there the length of the nickering light. In the ensuing darkness he seemed to be reaching a decision. His fist tapped the walls slowly, the weight of his body shifted and an arm touched Hackamore.

"I'm not pullin' my gun tonight, Hackamore. My word's on that. I'm going to do something I never did before and I hope I'll never do again. It's all up to you, Hackamore. We've got to see this weddin' day through."

"I got men scattered along the street. I'm havin' 'em ride beside yore rig, six on a side."

WILL DRUM'S voice fell to a murmur, he stepped nearer his

deputy and the words made a muffled pattern along the hall.

Hackamore held his peace until the sheriff was quite

finished.

"What makes you gamble on that?" he wanted to know.

"I'm bankin' on human nature, Hackamore."

"An' exposin' yoreself to open fire. By God, Will, don't yuh see the trap they're drawin' yuh into?"

"I'm matchin' Sam Horrell. I got to play up to his game tonight, Hackamore I got to hit him hard. So hard he wants to cry but don't dare. He's got to meet me at the fandango hall, where he never figgered I'd ever reach, and he's got to smile like a good citizen while the county sees him do it. And they'll know how I licked him—this time."

"And yuh takes a chance of a bullet in the neck."

"If they hit me at all it had better be a bullet in the neck," was Will Drum's brittle answer. "For I'll see 'em die! I'll track 'em down and I'll wipe that outfit from the county. Remember what I told you now and hustle along. We folks are about ready to move out. I'm dependin' on you, Hackamore. This is Kit's day and nothin' can spoil it. It's up to you now."

He touched Hackamore on the shoulder. The deputy muttered something and went quickly down the stairs and out the back way, to disappear in the rear lanes of the town.

As twilight gave way to a deepening dusk lights winked through the fogged panes of the buildings and gushed across the open door-sills; but, although nobody in the shifting crowd observed this, it was something more than an accident that these lights were almost all on the east side of the street.

From the lodge hall, now humming with guitar music and gathering couples, to the Palace and on along to the hotel was a parade of yellow beams, crossing the dusty thoroughfare and dissolving into the deepening shadows of the west side. It was more than accident that the west side showed only two or three stray points of light; for as the moments passed a Horrell man slipped quietly into two of these places and presently there was but a single lamp's reflection breaking the mystery of that street side. And when Will Drum and his new wife passed along in the rig, from hotel to hall, they would be riding through these saffron lanes, outlined against the glowing windows and doorways; a plain target for Arizona Tracy who at that moment lay on the dark side of the street with the muzzle of his rifle resting on the window sill of a second story room in the New York hardware building.

THE Palace boomed with sound. Horrell men walked up and down

the street and loitered at chosen spots. Sam Horrell and his kin

appeared in front of the lodge hall and there waited, as if

forming a committee to greet Will Drum when the latter arrived.

And then, when a rising tide of sound announced the appearance of

the sheriff and his wife on the hotel porch, Horrell horsemen

swept along the dust and Horrell men stood still in the pools of

shadows while, as if at command, the din and clamor in the Palace

redoubled.

The girl had a Spanish shawl around her shoulders and she was looking up to Will Drum with a smile on her lips, an arm hooked through his elbow; the rays from the hotel lamps glowed in the golden hair and revealed the flush on her cheeks. She was saying something to him. He nodded and straightened until he towered above the group around him. He wore the blue overcoat and more than one prying eye in the crowd looked toward Will Drum's waist and guessed there was no gun concealed beneath. He leaned toward one of his partisans and murmured a word. Then he helped the girl into the rig, sat beside her and spoke to the driver. "Go slow, Tip. All right." The escort formed a double line around the rig and they started down the street.

That was the signal for which the town waited. No sooner had the rig started off than a hundred guns spoke and a rocketing roar beat against the building sides and purple lights danced and veered in the shadows. The ancient, shrill yell of cattle land swelled, died and swelled again; horses reared, riders raced headlong through the confusion. The girl laughed. "Will, I love them all!"

"They're good boys," said Will Drum gravely. He saw a grim face flash by him—one of his partisans patrolling. Of a sudden he took the lap robe, folded it thrice and tucked it behind the girl's back. "Lean forward, Kit. It's a hard seat."

"But we've only got a hundred yards to go, Will."

"Comfort is comfort, even for a hundred yards," he murmured. The bulk of the robe placed her forward in the seat; Will Drum leaned back and a kind of set intensity took hold of his bronzed features. He looked to right and left and thereafter kept his glance ahead. The lights of the Palace swirled around them, harness gear shimmered and once more the guns sent a fanfaronade toward the sky. The lodge hall was directly ahead. Will Drum flung a swift phrase to one of the escort. "Keep it up, keep the guns goin'!" There was little need for this injunction; every weapon in town added to the chorus until the ears rang with the concussion of it.

Will Drum turned his head ever so slightly, like a man listening.

Through and above the tumbling detonations of sound he heard that particular echo for which he had been listening and from the corner of his vision he saw a solitary flash high up in a building window. There was a short, muffled cry; Horrell men stirred along the sidewalks and the members of the escort bunched in more closely. Will Drum drew a deeper breath and fastened his eyes to the assembled Horrells by the lodge door. Sam Horrell stood foremost, his burly head bent in advance of his shoulders, turbulence boiling in his black eyes.

The rig drew abreast the door and stopped. Will Drum stepped down and gave his hand to the girl. Sam Horrell bowed toward her and for the moment his face was hidden from the crowd.

"Well, Sam," drawled Will Drum, "I see you're waitin' to welcome us. That's plumb nice of you, Sam."

SAM HORRELL'S head rose. His hat came off and he smiled toward

the both of them with perfect courtesy. "May it be a long life

an' a happy one, which is the wish o' me and all my men."

The girl smiled; Will Drum returned the felicitations with equal courtesy and so they stood for an instant, watching each other with outward politeness while the tide rips of intrigue swirled around them. Inside the hall the guitar players struck a tune. Will Drum nodded to the girl and they passed in, leaving the escort sitting silent and watchful and still a-saddle. Sam Horrell turned and presently was lost in the shadows.

He ducked through an alley and came upon the back entrance of the New York hardware store, an area cloaked in darkness. Somebody moved uneasily in front of him, challenged him.

"What the hell happened?" snapped Horrell.

"Oh, you, huh? They're a-bringin' Arizona down. He never got in a shot, Sam. Well, he fired, but it went way wild. Somebody put a bullet in his chest from acrost the street while all that yellin' was a-goin' on. Dead."

Boots groaned along the back stairway, voices murmured.

"Easy. All clear outside?"

"Come on," growled Horrell. "He's finished?"

"In the heart. By God, let's go clean 'em out now! Ain't it time? They can't get off with that. Not by a damn sight!"

"Shut up!" muttered Horrell. "This is buried, see? Not a word of it goes out. You boys get him clear of town. Take him to the ranch. Get him under the ground before daylight. Arizona—why, he was my best man. Damn you fools, quit parleyin'! Get him out! No more war talk outen you. We got to put a good face on this. Somethin' went wrong."

"Is Will Drum runnin' this country?" broke in a voice angrily.

"Tonight I guess he is," said Horrell. "Wish I knew how he discovered this. Arizona—we'll see about it later. Get him out of town. And the first man that talks I'll kill!"

THEY moved off with the dead Tracy. Horrell retraced his way

toward the dance hall. And presently, from a near covert,

Hackamore Weaver emerged and likewise went toward the hall. He

ambled casually into the place, blinking his eyes against the

light, and made for his chief. Kit smiled at him. "We have missed

you, Hackamore. Where have you kept yourself?"

"Had a chore," said Hackamore. "If I had any nerve I'd kiss the bride."

Drum and Weaver grinned at each other. Sam Horrell cruised across the floor. "I believe I claim the first dance, Miz Drum. Want to put in a word before the rush starts. That agreeable, Will?"

Will Drum nodded and Sam Horrell led her away. Hackamore spoke from the corner of his mouth, seeming to watch the dancers.

"I got him, Will. But how did you know he'd be up above the hardware store, anyhow? An' how'd you know I should cache myself right opposite an' wait for him to shoot?"

Will Drum wiped a film of sweat from his forehead. "It's something I never want to do again, Hackamore. But I gave her my word there'd be no gun play to spoil her weddin'. I had to keep it somehow. She won't ever find out. Hackamore, you're the only man ever I'd trust with a chore like that."

"Yeah, but how did you know?" persisted Hackamore.

"Sam Horrell gave himself away. You know that habit of writin' an' drawin' on paper while he talks? It gave him away. He told me this mornin' he meant to be peaceful. But he had another idea in the back of his head an' he scribbled it down on paper, not realizin' he did it I sorter caught on, but I wasn't sure. That's why I had you go look in his office to see what you could find. He gave himself away on that second sheet of paper you brought me, too."

"You don't mean to say he deliberately wrote what he aimed to do?" protested Hackamore. "He ain't that foolish."

"On both those pieces of paper was a lot of flourishes," explained Will Drum, watching his wife move across the floor. "And every once in a while there was a couple of letters thrown in for good measure. Those letters gave his scheme away. Ever be talkin' to somebody, Hackamore, and at the same time scribble on paper or draw figgers in the sand? Lots of times what you're actually thinkin' gets into those figgers an' you don't realize it. Same with Sam Horrell."

"What were said letters?"

"N Y," said Will Drum. "What else could that mean than the New York store? And if he was plannin' on ambushin' me in town—which I knew he was—why not somewhere about that store. So I cached you across the way. And it worked."

Sam Horrell came back with the new Mrs. Drum and left her with a profound bow, threading off through the couples. She watched him go.

"How pleasant a man he can be when he is in the humor. It seems to me he is trying to be agreeable to you, Will."

Drum and Hackamore exchanged glances. "He's got to be—tonight," said Will. "Maybe not tomorrow or the day after tomorrow—but tonight."

The music went on. Outside the sheriff's self-elected escort loitered, waiting for an issue that had come and passed without their knowledge. Horrell men drifted through the darkness, waiting for a word that failed to arrive. Intrigue stalked the streets of this town, but tonight Will Drum had enforced a truce for the sake of his bride.

Short Stories, September 1951, with reprint of "Fandango"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.