RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

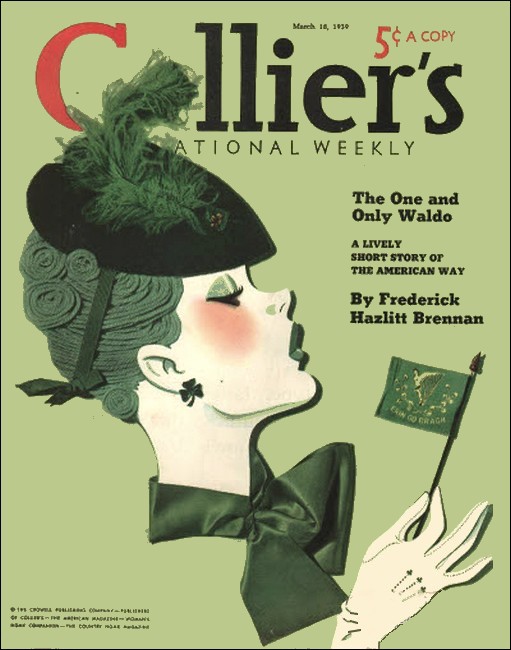

Collier's, 18 March 1939, with "Fourth Son"

SAM HILLIS, who had been driving cattle up the Chisholm more years than he liked to remember, rode down the sharp-pitched trail and stopped before a scene that was pretty familiar to him. Here squatted the low 'dobe Harpenning ranch house between the red walls of the canyon. A creek clattered shallowly across its graveled bed, shadowed and made cool by the grove of live oaks. Beyond the mouth of the canyon was a vista of flatlands undulating onward into the blue horizons of West Texas, and spring was in the small wind as bland and fragrant as a man might ever breathe. Lissie Harpenning, so silent a woman, was at the 'dobe's doorway. Adna Harpenning had paused behind his boy Bill, studying out the things that were necessary to say; and here was Bill, the fourth and last of the Harpenning boys, ready to go up the trail as the others had before him.

Adna Harpenning said: "Where you drivin' this year, Sam?"

"I sent the herd away this mornin'," answered Hillis. "It will camp tonight at the White Tanks, which is where I propose to overtake it tomorrow. I'll be by before the rooster crows and pick Bill up. That gives him another day with you folks. We should be at Fort Benton, Montana Territory, by the first of September. You can expect Bill back here by October, with money in his pants, Adna."

That last phrase was a deliberate addition; it was a concession to a feeling he could not help as he watched the bright fever of excitement burn in the eyes of this disturbed and string-tall Bill who was not yet a man. Well, it was a familiar scene. This was the way the three other Harpenning boys had looked as, each in turn, they had stood before him with that hard unrest of youth so plainly showing on them. He had taken them up the trail, and now here was the last one straining to be on the go.

Sam Hillis bent in the saddle to scratch his high mare between the ears, which was an excuse not to look at the Harpennings for a moment. None of the other boys had realized how this thing went with the old people, nor did Bill know now. But Sam Hillis knew.

He said: "Kind of anxious to be on the road, Bill?"

"Why, yes," said Bill Harpenning. "Yes, sir, I reckon I am."

"Seventeen," said Sam Hillis, "is a tough age. Nothin' moves fast enough and everything is too blamed far away. But"—he had raised his eyes and was mostly talking to Adna Harpenning, and to Lissie in the background—"you can figure Bill back here by October, money in his pants."

Thirty years of West Texas had put a mark on Adna Harpenning.

His shoulders came down at the points and his arms were very long

and his hands blackened and sprung at the joints. He had gray-blue

eyes above a clipped white mustache and his voice was softer than

the wind, with a thorough courtesy in it. "The money," he said,

"will help, but it ain't the money so much. It is time Bill took

the next step."

Adna Harpenning's words had a meaning for Sam Hillis alone. Adna was sending his boy out to be a man, if the trail would let him. The trail was the world. It led anywhere young Bill wanted to go; it might lead back to this box canyon, or it might not, but wherever it led, its hardness and its risks would season him or break him. There was no other way. This was why Adna Harpenning's voice was so slow and so even.

Sam Hillis nodded, watching Lissie Harpenning's hand leave her forehead in a slow, loose fall. Sam Hillis cleared his throat. "Heard from your other boys lately?"

"No," said Harpenning, in the same summer-milk tone. "I guess they been too busy."

Hillis thought: Bowie went up the trail six years ago, Ray's been gone four, and Crockett left three seasons back. He remembered each one distinctly. They had stood where Bill stood now, just as impatient, just as thin and unformed, with Adna Harpenning in the background watching and with Lissie Harpenning at the door listening. Sam Hillis pulled up the reins. "Be here before the rooster crows," he repeated, and cantered down the canyon.

Bill Harpenning went around on his heels to face his father. Excitement moved inside him like high wind, and his Adam's apple crawled up and down his throat. He said, "If there ain't nothing to do, I think I'll ride down the creek."

Adna Harpenning said, "Ride along," and watched his son go about the house in loose, long strides. The boy's shoulders were heavy-boned and would be pretty solid when they fleshed out. His flanks were mighty small from growth and from riding, but they, too, would fill. This was what Adna Harpenning studied on as he watched young Bill swing to saddle and head down the creek; this was what he thought, critically, and with an affection he would never be able to show. Lissie had gone into the house. He found her at the kitchen window, following young Bill with her eyes. She said over her shoulder, "Gone to see Helen?"

"I'd expect so."

"Should have waited for his meal. It ain't like he didn't need to eat. None of the others were that thin, Harpenning."

West Texas had put gray in her hair, it had thinned her lips and turned her mostly sober, but it wasn't much of a trick for him to watch her, as she stood against the window's light, and see her as of old. She had been a redheaded woman from Caddo Parish, Louisiana, with a cream-white skin and a smile that could run up a man's heart. It was a good memory and it showed on him, for her lips parted faintly and she spoke to him, half in sharpness, half in affection: "Harpenning, what you doing in the house this hour of the day?"

The onrunning silence was like speech, which was the way it got to be with a man and a woman after thirty years of pretty close living. She was thinking of Bill, and then she was thinking of the other boys who had gone up the trail, neither to return nor to write. Well, none of them were the writing sort, but—

He said: "Kind of odd to recall how they were. Bowie, now, was a thrifty one—like you. A natural-born trader. Ray had no weakness except his temper. I always wondered how he came out. As for Crockett"—he paused and watched his wife and qualified his words—"I never knew much about Crockett's head. I wish I did. Bill's the best of the lot. I have no fear for him."

She listened, and yet he saw that she was not altogether listening. That farness was on her face as though she were seeing those other boys. She murmured: "They didn't come back, Harpenning. Neither will Bill."

He was an illiterate man, whose wisdom came out of his own slow, thoughtful, earthy life. Before her, he had always an unvarying gentleness; his voice was kind and easy and a little different: "Man must take his own way, Lissie. That's about all we could ever tell those boys."

"I wish," she said, in the same remote tone, "I could have seen grandchildren. Bowie would be having children by now. I wish I could see them."

"I wonder," murmured Adna Harpenning, "what Bowie's doing."

High above the house the summits of the Bighorns were still snowed

in. Tensleep Creek rushed by the porch, water-gorged to its brim.

Snowflakes, damp and dollar-round, still fell, but the wind had

hauled about earlier in the morning and the breath of the chinook

had the warmth and smell of spring. Westward the flats lay clear

and cattle were browsing the winter-gray grass. This was what Bowie

Harpenning saw and felt when he came out of the house—this

sudden onset of another year. His oldest boy, not quite five, came

out and stood by his side.

"I'm goin' to Texas this mornin'," he said.

"Why, now," said Bowie Harpenning, "that is quite a mornin's ride for one horse and one man. It would be a thousand miles, sonny."

"Grampa and gramma's there."

"Maybe they are," mused Bowie Harpenning. "Maybe they still are." His eyelids closed a little, wrinkling at the corners from the effort of looking back across time and distance. It was the talk of his boy and the smell of spring that brought back the seldom-recalled memory of the 'dobe house under the live oaks; and there was a small, odd stirring in him and a vague recollection of his mother making butter in the wellhouse, and the drowsing silence of the red-walled canyon wherein the shallow creek splattered over its graveled bed. They were alive for a moment, these scenes and impressions, and brought some vague feeling with them; and then he heard the croupy cough of the baby inside the house, and the past, which was never very real to Bowie Harpenning, left him quickly and completely.

He said: "Put on your sheepskin, sonny, and we'll ride down to the flats."

Bill Harpenning rounded in at the King ranch below the canyon, had

his dinner there, and afterward joined the bronc busters in the

corral. When Helen came from the kitchen he left the corral and

joined her; then, together, they rode out into the steady flatness

of the plains.

She was a straight, man-raised girl with a face browned by the wind and sun, and something like a boy in the way she rode. There was no talk, and no sound save the soft abrasion of saddle leather and the punky scuff of the ponies' feet. Willows made a grove at the bend of the creek five miles south of the ranch and here they stopped, as by long habit, and let the horses stand. They walked along the edge of the creek, slowly. He had his head down, and his face was sharper than it had been, and troubled.

"I'm leavin' in the mornin'."

Her pace quickened until she was ahead of him, until he couldn't see her face.

"Why do you have to go?"

"Well," he said, and stopped, knowing no answer. He looked beyond her, at the north, and his face was thinned down from what he was thinking and there was a glow in his eyes. She saw it and her coolness went away and she said sharply:

"You're going just like your brothers, and you won't come back. Why should I care?" She pulled her shoulders back, and her hands were straight beside her, doubled tightly, and she was crying.

He spoke in a shocked, groaning way: "Why, Helen! Everybody's got to go up the trail once. A man's got to see what's there. A man's got to know what it's like. I'll come back."

She shook her head and bent it until the tears were gone, and looked up at him again, direct and unsmiling. "I guess," she said, "if I were a man I'd go too. I guess you got to. But you'll go up there and you'll see something, like your brothers, and you'll forget Texas." She paused, watching the dark shift of expression on his cheeks, his uncertainty, and the formlessness of all that he felt. And then she was again cool and careless. "A girl's different, Bill. I'm seventeen—and that is getting old, not to be married."

He shot her a strained glance, a disbelieving glance. "You'll wait for me, won't you, Helen?"

She murmured, so softly, slightly sad: "Maybe, Bill. Maybe not. A year's pretty long. In a year I'll be eighteen. I was born when my mother was eighteen. Maybe—maybe not. We better go back."

Paused by the washbasin, with water hanging to the long transverse

lines of his cheeks, Adna Harpenning watched his son come up the

canyon in the first swirl of dusk. Twilight dripped in slow,

adhesive streams down the canyon walls, and the smell of the land

was sweet and pungent and cleansed. Light made a yellow rectangle

of the doorway and when Adna Harpenning stood in it momentarily,

the silhouette of his frame was long and narrow and faintly curved.

He waited for Bill to wash; he said: "King's?"

"Yeah."

"A night like this," observed Adna Harpenning, "is kind of pleasant for ridin'," and passed into the house. At the table he bent his head and paid his respects to the Lord. "Bless these provisions to Thy servants, O Lord, and make us useful in Thy sight, and, Lord, protect the young that do travel far from home. In Thy name, humbly. Amen."

There was, he saw, no appetite in his son. Bill sat idly to his plate and the morsels of smoked ham and fried corn cakes seemed no pleasure to him. This was no new thing, though tonight there was an added reason, which would rise from Helen King.

"I once recall," said Adna Harpenning gently, "that I took occasion to differ with your mother some time before we was married. I reckon in the end she was right, but at the time it seemed different. That was a kind of uneasy week, in which I never set foot by her house. It had something to do with another man. It came to me I should kill the man dead, and I mighty near arrived at that act."

Lissie Harpenning turned her eyes toward him. Her face softened, and was tolerant with his humor and a little shy from the memory. "Harpenning," she murmured, "I was anxious for you to ask, but you were backward, and so I made some talk with Antone Dulac to make you take closer notice." She watched him, turned young by the memory for a moment, and said gently, "It made you mad. But you asked me the next week."

"I have no regrets," said Adna Harpenning.

They sat at the table, these three, each caught in his own deep recollections. After a time, Bill rose. His body cast a thin high shadow on the 'dobe wall and his long arms hung motionless for a moment. "I guess I'll ride down the canyon," he murmured, and went out.

They listened to his horse crush along the creek's gravel. Lissie Harpenning's shoulders straightened and her eyes were round and concerned. "He don't eat enough, Harpenning."

"The best of the four," mused Adna Harpenning.

"This table used to be too small for all of us," she sighed. "Tomorrow it will be too big. When they were all little boys, Harpenning, I used to think the noise would make me cry. But it's hard to stand the quiet now. What will we do, Harpenning?"

Wrinkles, small and deep, netted around his eyes. His hand, stretching out to touch a scar in the edge of the table, showed sinews prominently against loose flesh. "I recall when Ray sat there and dug his knife into the board. The boy was put out because I would not let him drive the hay wagon. Always did have a quick disposition."

"Harpenning," she said, "where would he be now?"

The year Ray Harpenning went up the trail somebody struck gold in

the headwaters of the Salmon River, over in Idaho; and that way Ray

turned. There was pay dirt on his claim, but he looked at the four

walls of his cabin until one day, sick of his own voice, he

deliberately blew in the drift tunnel with a stick of dynamite and

turned to the boom town twenty miles away. Next year, because he

had a way of getting along with men, he was named marshal; and that

same year he met a girl.

She was the daughter of a townsman and when he looked at her she smiled and said: "You are very young to have so big a reputation." For he had killed his man, in the course of duty, even then. There was a streak of rashness in Ray, and he saw it in this girl in the way she laughed at him and wasn't afraid of him. Within a month he had asked her to marry him and had been accepted.

One week later, coming out of the Crystal Palace saloon, he saw her walking home with Hans Pardo, who owned the Caroline mine in the Winter Valley. Paused by the saloon, Ray Harpenning watched the two cruise along the walk, and saw Pardo remove his hat at her gate and speak something that made her smile. There was a quietness in Ray then, greater than any quietness he had ever felt before, and when Pardo came down the street again, Ray met him at the saloon's door.

"Hans," he said, "you're a little forward in your ways. I'm marrying that girl. Stay away."

Pardo wasn't smiling, but back of his eyes was something like insolence, not to be endured by Ray Harpenning. Pardo turned away, saying nothing at all, and Ray knew he was going after a gun; and he waited by the Crystal Palace, drawing the strong fragrance of a cigar's smoke through his lungs until he saw Pardo come around the corner of the hotel with a pistol on his hip. Ray dropped the cigar to the street's thick dust. A boy sat on the edge of the walk and Ray, crossing to the street's center to meet Pardo, said, "Move out of here, sonny," and waited till the boy had turned down a side alley.

A strong sun hung above him, and the street lay without shadow before him. He saw the girl standing by her gate, up the street, and he lifted his hat to her, smiling, and replaced his hat and turned directly around to face Pardo, drawing as he turned. There were two shots, the echoes bursting side by side and racing together all through the town, and afterward the girl cried his name and ran toward him. But deep in the dust, face down, he never heard her.

At three-thirty in the morning, when Adna Harpenning stepped out of

the house to wash up, Bill came up from the barn with his

horse.

Adna Harpenning said: "I guess you better eat, Bill. Sam's like to be here early enough. I never knew him late on his word."

He followed his son into the house, putting his hand against the boy's back as if to push him along, though this was not the reason for his touching his son. He felt the faint warmth of Bill's skin through the cotton shirt, and the thinness of the muscles covering the boy's bones; and at once he felt the full force of a keen, hard anxiety that he could not reveal. This was his son, who would be bucking the trail, its cold gray rains, its dusts and its blazing heat, its tricky quicksand rivers and midnight stampedes and its tough, man-eating trail towns. A man went through these things and forgot them until the time came to send his sons along. Then it all came back, pretty real.

The kitchen was warm and light and its smells were nourishing. At the table Adna Harpenning bowed his head. "Bless these provisions to Thy servants, O Lord, and make us useful in Thy sight, and, Lord, protect the young that do travel far from home. In Thy name."

Lissie turned from the stove and placed Bill's hot cakes before him, and poured his coffee. She stood beside his chair, looking down, watching his face.

There was a gray-stained light showing at the window and a rider scuffed down the east side of the canyon, strongly calling: "All out for Montana."

Lissie Harpenning put down her coffeepot and stood with both hands before her, straight and still. Bill came up from his chair. He swung to the door and paused, and came back to his mother, looking down at her; whereupon Adna Harpenning quietly left the room.

Sam Hillis sat in his saddle, his ruddy cheeks beginning to show in the growing light. He said, not impatiently, "Time to go, Adna—Montana's a long ride."

"Sure," said Adna. "The boy is comin'. He's spendin' a minute with his mother."

"The fourth one—" began Sam Hillis, and quit on that. Bill came out of the 'dobe carrying his gun and belt over one arm. He stood before the men, throwing the belt around his waist, notching it up. Lissie Harpenning appeared in the doorway and put a shoulder against the jamb. Silence lay across the yard and across the canyon.

Adna Harpenning said, "Son," and walked to the edge of the house. He picked up a small can and paced away and dropped the can. He stepped back toward a live oak tree. He said, "Try that, son."

Bill Harpenning lifted the gun and turned. He weighted the gun in his fist and let go twice, knocking the can on along the yard. Sam Hillis's horse pitched gently and Adna closed in until he stood quite close to Bill. "I guess that will do. Never draw unless you mean to shoot and never shoot unless you mean to hit. I got but one thing more to say: use no words on any man that you wouldn't want him to use on you. Now you better dust along—it is gettin' late."

"Sure," said Bill Harpenning, and walked to his horse.

Lissie Harpenning stepped out from the doorway. "Bill," she said, "if you see any of the boys, tell them to write. It has been kind of long. If you see Crockett—"

It was gray daylight, and the end of an all-night game in Deadwood.

Spot Frazee said, "Call," and laid down his cards. Crockett

Harpenning looked at them, no expression on his face and no

disappointment in his voice. All he said was, "Good," and threw his

hand into the discard. Jim Burkitt started shuffling but Crockett

Harpenning shook his head. "I guess that's all, boys," and he sat

there while the rest of them rose and stamped the stiffness out of

their legs and went away.

Cigar ashes grayed his black broadcloth suit and there was a whiskey mark on the front of his white shirt. One barkeep slowly polished the back bar's mirror and a roustabout was sweeping up the sawdust and dirt over at the foot of the gold scales—a gleaning he would presently pan for spilled dust.

Crockett rose and passed to the bar and silently signaled for a bottle. He took a drink straight and quick. The saloon man said, "Cleaned?"

"A little run of poor luck," admitted Crockett.

"Well," said the barkeep, "I guess that's the way it goes. But if I was you, son, I'd pick another trade. You're still pretty young."

Crockett Harpenning left the saloon, facing the steady rush of wind coming down the canyon. Below lay the formless blur of Deadwood's lower quarter, here and there marked by a quick winking point of light. All the higher hills were snow-covered but there was a softening of the wind's edge to tell him of spring soon coming. It was this softness that reminded him, as he stood irresolutely on the dark street, of the red-walled canyon in West Texas. He remembered it suddenly and with a fullness of feeling that held him entirely still. Then he pulled up his coat collar, patted his right pocket to make sure the derringer was lodged there, and tramped the loose boards toward the lower end of town.

"Sure," said Bill. "If I see any of them, I'll tell them to

write."

"Well," called Sam Hillis, "time won't wait."

But young Bill suddenly slipped to the ground and went back and shook his father's hand and crossed to his mother. He bent over. He said, "Good-by, Mom," and kissed her, and ran back to his horse. In another moment he was in the saddle, leaving the yard at a full gallop. Sam Hillis followed.

Standing there, Adna Harpenning watched the boy reach the east rim and pause to wave, and dip on out of sight. Swinging about, Adna noticed that Lissie had gone into the house, whereupon he circled the back yard and came to the chopping block. He sat down here, rolling a cigarette and listening to the small, waking sounds of the day—and listening, too, for a sound from the house. But there was no sound and then he remembered that Lissie never cried. A magpie flashed across the yard and the east rim began to blacken against the strong glow of the morning and above him in a cottonwood tree he noticed a deserted bird's nest.

He rose and went into the house, finding Lissie seated on the edge of the bed in the room that had belonged to the boys.

"Harpenning," she said, "he won't come back. The others didn't, and he won't."

His tone was gentle with her, as it had always been: "Why, now, it may be that way. But I guess it is like that nest in the cottonwood. They grow and feed, and then they leave. What else could we be expectin', Lissie? It is the way all things go. It is the way we did, when we got married. I reckon there's many a time we thought of Louisiana, and I guess we would like to have gone back. But we never did. Our good times was in raisin' 'em..."

"Harpenning," she said, "it is a mighty empty house. He didn't eat, and he was sore troubled."

"The best of the four," murmured Adna Harpenning. "The trail will be his seasonin'."

He turned, not knowing how else to comfort her, and stood by the window, looking out to the canyon's west wall. He raised the cigarette, taking a slow breath of smoke.

"Come here, Lissie."

She delayed the coming until he turned and beckoned again. He moved away so that she might face the window, and he pointed through it. "Lissie," he said, in a voice that lifted out of his chest, "this boy will come back. The others never had a reason to return. But this boy will come back when fall's here. You see?"

His arm pointed upward to the west rim of the canyon where, shaped against the strong brightness of full morning, Helen King sat on her horse. She had her arm lifted high above her head, and she was signaling across the canyon to that other side where Bill Harpenning rode.

Lissie Harpenning turned and for a moment Adna saw her as she had been in Caddo Parish, a calm, redheaded girl with a smile that meant everything. This was the way she looked at him now, and said:

"It will be nice to see grandchildren, Harpenning. I can be contented with that."