RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

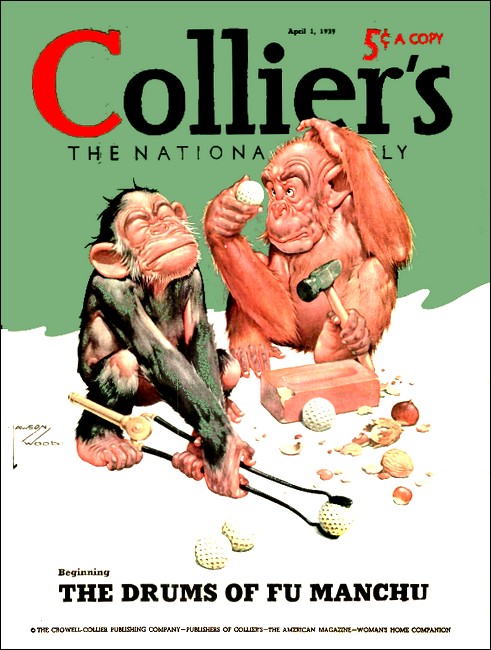

Colliers, 8 April 1939, with "Good Marriage"

AT evenfall this Saturday, with supper done and the soft

sweet-smelling shadows of summer drifting against the prairie

like gray gauze, neighbors began to come in. The Hurds were the

original homesteaders on the Silver Bow's south rim, having

settled this quarter section at a time when the cattlemen still

made it dangerous for a nester, and so it was natural that the

Hurd house should be more or less a gathering point. In any event

Sam Hurd, who loved a sociable evening and loud argument better

than most men, usually had a keg of beer cooling in the well and

this was a powerful inducement to the lean, dry and clannish

Missourian settlers—the Gants, the Lockyears, the Cobbetts

and the Prillifews.

The children were all outside, running through the shadows, their quick-issued cries riding the night. Men sat around the room, chairs canted back against the wall, and the women were together at one end, now and then speaking among themselves, but always listening with half an ear to the talk of the men. Tobacco smoke laid its pall around them, so thick that the table lamp cast a mist-blue shadow; the smell of fried pork lingered in the house and the warmth of the day held on. Mrs. Prillifew's new baby began to cry; she unbuttoned the front of her dress and slid it down from one shoulder, uncovering her nipple to let the baby nurse; its small mouth made a steady, smacking sound.

Lisbeth Hurd moved over the room, straight and large-breasted and robust; at twenty she was the oldest of the Hurd children, pretty enough to bring the eyes of men around to her with a covert interest. She took Cobbett's empty glass, refilled it at the beer keg and passed it back to him; and stood by the beer keg, watching the men and indifferently listening. The sludge of Henry Zimmer's pipe began to fry. He reversed the bowl against his heavy hand, emptying it and refilling it. Henry Zimmer was one of the Hurds' two boarders. Bob Law, sitting longlegged in the doorway, was the other. Both these young men were building shanties on new quarter section claims across the deep canyon on the Silver Bow.

Lisbeth Hurd watched Henry Zimmer's square face glisten when the lighted match played across the pipe bowl; nothing hurried this man and nothing much moved him. Talk broke around her, idle and cheerful, and slowly her glance turned to Bob Law in the doorway. Bob Law nursed a cigarette, his head dipped aside as though he listened to the night or saw pictures on the far prairie; the silhouette of his face was long and taciturn and sharp. Studying him, Lisbeth's expression was tight-caught by soberness, her eyes had a depthless dark in them, her shoulders moved faintly.

Sam Hurd, who never was able to speak in a tone less than a half-shout, said: "It don't do no good to grow a lot of fruit. A man's only got so much time and it don't make sense to waste it waterin' a lot of trees. You got to raise things in this country that can shift for themselves, or you break your back."

Henry Zimmer spoke up, dogmatic and calm. "I grow hay, when I get started. I grow hay and feed stock. I run a feeder ranch, like they do in Iowa. Maybe I try corn."

Sam Hurd listened approvingly. This young man was after his own tastes, thrifty and marked for success. Down the road they heard the steady clip-clop of a trotting horse, whereupon Sam Hurd said: "Who was that I heard goin' by here two o'clock the other morning in a rig?"

Cobbett answered: "Bill Shasto, bringin' Nellie Grace home. Nellie told her old man they had trouble crossin' the ford."

Sam Hurd let out a great burst of laughter and all of these men were grinning, knowing Nellie Grace. Hurd said: "She better marry Shasto before the baby comes along."

"Like Pete Root's wife," offered Prillifew. "Pete still claims it ain't his boy."

"Whut should he care for?" countered Sam Hurd. "It's one more boy, for chores." He swiggled the beer around his glass, pleased with the smoke and the warmth and the comfort of neighbors; suddenly he reached forward with his broad hand and hit Lisbeth across the hips. "Lisbeth, there's a thought for you. Get your man to take you out in a buggy."

Lisbeth turned her dark eyes on her father, unstirred and unembarrassed. "What man?"

"My God," said Hurd, "you got the choice of anybody on prairie."

Mrs. Hurd's voice was a steady tone on the edge of all this. "You parboil it fifteen minutes, change to a little fresh water and add the kraut." While she talked her eyes watched Lisbeth carefully, seeing Lisbeth's glance swing and stop on Bob Law at the doorway. "The flavor comes from not leavin' the kraut on the stove too long."

The clip-clop of hoofs died in the yard and an assured young man, sandy-haired and smiling and dressed in neat townsman's clothes, picked his way across Bob Law's outstretched legs. "I saw the lights and heard the noise and thought I'd say hello."

This was Cam Skelton, who owned the drygoods store in Prairie City; and since he was in a way foreign to the slack, comfortable homestead group, Sam Hurd accorded him the courtesy of rising. Mrs. Hurd left her chair, pleased and somewhat disturbed at his presence. "Lisbeth, get Mr. Skelton a glass of beer. You mustn't mind such an untidy house, Mr. Skelton."

"It is an attractive house, Mrs. Hurd," said Cam Skelton with his most gallant manners. He paid his respects to the women with an inclusive statement. "You homestead ladies are the finest housekeepers in the world."

"We eat well," admitted Sam Hurd. "Had supper?"

Lisbeth moved around Cam Skelton, drew a glass of beer, and offered it to him. He said, "Thanks, I've eaten, but the beer will be a pleasure after the ride." He saluted Lisbeth with the glass; over its rim his eyes held her—they were quick eyes, round and bright-colored. From the corner of the room Mrs. Hurd watched this man, the way he looked at Lisbeth. Talk had ceased in front of the townsman but he finished his beer and brought the talk alive again in an easy way. "It has been a good year. No grasshoppers and no drouth. There's a new settlement going in below town, on the Sweet Fork. Time will come, Sam, when you settlers will have the cattlemen pushed back beyond the bench."

"Time will come," said Sam Hurd in his loud, positive voice, "when we'll pass the laws in this country, and by damn we'll scrunch them like they have been scrunchin' us."

"Thanks for the beer," said Cam Skelton. He paused a moment, cool enough to disregard the crowd while he put his glance on Lisbeth. There was a full interest in him; she saw it as she stood calmly before him, not showing expression. Presently he ducked his head at the group and left the house. Silence held on until the pacing of his horse softened in the distance. Then Sam Hurd said: "As for corn, Henry, the Ioway kind won't do out here. We got to get a seed that will stand dry weather. Well, it will come." Talk rose up again and the tobacco smoke blurred everything.

Lisbeth drew a glass of beer and moved to the doorway. She stood there, looking down at Bob Law until his face lifted. She said, "Beer?" and watched him take it and look away. The top of his head was dyeblack; there was a scar on his cheek, which was part of his past—from a horse or a man or from a woman. She didn't know. He was a cowpuncher who had ridden out of the hills to take up a quarter section and the way of his life had left him taciturn. He wasn't at all like the practical, heavy, loudspeaking homestead men. He was loosejointed and narrow-hipped from riding; he was an easy swinging man but at times he moved with an astonishing swiftness; something was inside of him, hard and intense and strange. But it was well covered. The open front of his shirt showed the bronzebrown skin of his chest.

The Prillifew baby was again mewling and it was time for the settlers to leave. They went away, family by family in their rigs, the children's backward calling riding the moonless night in undulating, long-sustained bars of sound. Bob Law had gone on to the corral. Idly following, Lisbeth put her shoulders to the corral bars, looking up at him. He didn't seem to see her; he stared into the black sweep of the prairie, he was listening to its vague voices and its silence. But she knew he was aware of her; it was something in the set of his body, in his stillness.

"Where'd you come from, Bob?"

"Off there," he said, pointing at the hills. He had the brief and flat tone of a man who didn't use his voice much. In the dark she saw his face come down to her and felt the sudden roughness of his eyes. He said, "Good night," moving away to the small tent at the edge of the corral. She watched the lantern light spring up; she watched his shadow turn and crook as he undressed and saw it stand straight for a moment. Then the light died and a little later she caught the thin smell of a cigarette; he would be lying on the cot, smoking in the dark.

Lisbeth returned to the house to catch up the beer glasses and straighten the chairs. The children had started to bed and Henry Zimmer had gone up to the spare room. She heard his boots hit the floor, one and then another, and the groaning of the bedsprings as he settled down. This would be all the sound from that room; he would sleep the night through, without motion, his heavy snoring making a steady echo through the house.

Sam Hurd said in a tone that was, for him, extremely mild: "Henry's a damned smart young Dutchman. There's your man, Lisbeth. He'll make a fine farm."

Mrs. Hurd said, "Ah," in a dissenting tone. She stood by the table, not speaking again until Sam Hurd slowly retreated to the corner bedroom. Afterwards she added: "Not him, Lisbeth. You've got plenty of choice. You make a good marriage. Look at me. I had no choice. I ain't sorry, I ain't complaining, but you got things different. You don't have to be a farmer's wife. You can choose. Why do you think Cam Skelton came here? You could live in town and drive your own rig. You could dress like those women do. You make a good marriage. You got the chance—just once you've got it."

In her room, beside the kitchen, Lisbeth undressed and got into her white nightgown and stood in the room's center, braiding back her hair. Her father's and mother's voices came from the corner of the house as a steady murmur, and died, and silence closed in. She blew out the lamp, opened the side door and stood in the velvet density of the night. There was a faint wind rising off the prairie; it ran softly along her body. When she leaned against the pump handle, its metal coolness was sharp against her breasts. From this porch she watched the black outline of Bob Law's tent, thinking intimately of him; and retreated to her room.

* * *

She stood in the yard, after breakfast, watching Law and Henry Zimmer saddle their horses. Henry had a solid plug, broad of beam and meant for the plow; it was an animal Law always looked upon with a faint show of irony, for his own pony was range bred and a little bit tricky on these fresh mornings, crowhopping around the dirt with Law sitting deep and careless in the saddle. When they passed down the trail into the Silver Bow canyon she noticed that Law had forgotten his lunch; but she didn't call him back. It was four miles across the canyon to where these two had their adjoining quarter sections; she would take the lunch to Law later. Back in the house she put the lunch on the side table and had her own breakfast with her mother and the smaller children.

Her mother said: "I want you to go to town. I need some long straight pins and five yards of gingham, red check, and a spool of white thread." She looked at her daughter carefully. "Wear your gray dress; it don't muss up in the sidesaddle." When Lisbeth was in the saddle and ready to go, her mother came out to give her two silver dollars and another critical survey. "You look well. You've got a way. Maybe it is a little bit like the way of women who don't live on farms. Be nice to him, Lisbeth. It is all you need to do."

Lisbeth said softly: "How nice?"

"A woman must think about these things. You want to make a good marriage. For some men, like Zimmer who is dumb, you can be forward. For some you can't. It is something you must find out for yourself, when you see what's on his face."

This was why she was being sent to town, Lisbeth knew; to be nice to Cam Skelton. The thread and gingham and pins were just extra. She went swinging down the road, with the blur of Prairie City in the distance. Dust rose behind her in a long pale diffused cloud, shutting out the view of the ranch. Across the Silver Bow canyon she saw the thin dots of two riders, which would be Law and Henry Zimmer splitting off to their claims. High on the southern ridge cattlemen raised dust with a driven herd and the sun was the bright half-hot sun of late September.

There were ways with men, as her mother had said. One way was Nellie Grace's way. For men like Shasto and Zimmer and many others, it was the quick and easy way to catch a man; but for Cam Skelton it would only shame her before him, for Skelton was a townsman with different thoughts. A woman could only hint, and not be common. These things Lisbeth Hurd knew; it was a knowledge that came out of some obscure place, to make her wise, to make her look upon the world with cool eyes. But then she thought of Bob Law and was not sure. For he was another kind of man; there was something in him, like a dream, like a picture. There were words for this but she did not know them, could not find them. He saw things in the sky, he felt things through the shadows that others did not.

Prairie City's street was a gray lane of dust between a long double row of stiff paintless buildings; wagons and horsemen moved along it as she passed on to the drygoods store, racked the horse and stepped into the cool twilight of Cam Skelton's store. She heard Skelton's voice before she saw him. It was the quick, rising voice of a pleased man. He came out of the rear shadows, his round eyes aware of her.

She said: "Some long pins, some white thread—and five yards of gingham, red checked pattern."

He had a light way with his talk. He said, "What's in you anyway, Lisbeth? I wish I knew." He touched her hand. "Be easier if I did."

"Checked pattern," she said and let her hand drop.

Afterwards, having bought these things, she waited for her change. This store was still and fragrant and empty. Cam Skelton's steps made queer softened echoes in it. She thought of her mother's advice with a distant interest, and watched Cam Skelton come back. He put the change in her hand, and took her hand. "If I brought a rig around tonight, Lisbeth, would you ride?"

"No-o," she said, "not tonight."

"Some night?"

"Some night," she said and made her small smile for him. She was a well-shaped girl, graceful even in this motionless attitude, with her mouth softened by the smile and her eyes meeting him coolly.

He said at once, "You don't need to run away from a man, Lisbeth," and brought his hands up. He touched her shoulders and then she felt his resolution and his sudden change of temper as he pulled her toward him. The brightness had gone out of his eyes; they were rough-gray and full of a thing clear to her. She didn't know why, but she struck his arms down and hit him in the chest and went by him, angry enough to kill him. He called in an irritated voice: "Wait," and she paused at the door and swung around. He came up to her, his pride stung. Suddenly he was a little man, small of wrist and shoulder, smelling of his own store; and in this critical, outraged light she looked at him, and spoke her mind. Across the street stood the saloon with its second-story windows showing green drawn shades—hiding the women who lived there. She said: "If that's the way you feel, go over there—above the saloon."

He said: "That's a hell of a thing for a girl to say. I guess I judged you wrong. What did you come here for anyway? Just for eighty cents' worth of goods?"

She marched out, with the package under her arm, stepped to the sidesaddle and ran out of town, still angered. But halfway home she suddenly smiled to herself. It was nice to know she had a woman's attractiveness. It helped; it made her feel something she hadn't felt before. Maybe he was wrong about her—but maybe he wasn't. What was a woman? What was she when she looked at Bob Law and had her own warm thoughts? What was she when the wind blew its strong wild smells down from the benchlands and stirred her heart; when she walked through the dark earth's shadows and felt the strength of her body like a heavy weight? There was no sign of this on her face; she was an idle girl swinging to the pace of the horse, color soft on her cheeks and a stamped gravity in her eyes.

She stepped off in the yard before her mother, who said eagerly: "Maybe you asked him out to supper?"

"No," she said. "I never thought of that." She went by her mother, caught up Bob Law's lunch, and returned to the horse.

"Maybe he said he'd come to see you?" said Mrs. Hurd.

"No," said Lisbeth, "he never did," and trotted down the canyon trail.

From the height of the rim the river was an urgent, winding streak far below, held in by the gray and yellow canyon walls; at the bottom of the canyon she crossed a shallow gravel ford, passed through a little cluster of willows and rose slowly to the south rim. Before her lay the sage-covered flats, running far to the empty north, directly ahead stood Henry Zimmer's fresh homestead shanty, its raw boards yellow in the sunlight; a half mile to the left stood Bob Law's house. Threading the sage as she went that way, she flushed slow-hopping jack rabbits from covert. Coming nearer she saw the pile of dirt mounded near the house, which was from the well he was digging. At intervals he appeared from the well, hauled up a bucket of dirt, dumped it, and disappeared in the well again.

She turned the horse over to the well and sat in the saddle, watching. He was twenty feet down, loosening the soil with a shorthandled pick and dumping it into the bucket; he had a ladder rigged against the well wall, and when the bucket was full, he climbed out and windlassed up the bucket; it was the hard way of digging a well—and a little bit dangerous at this depth.

She said: "You forgot your lunch."

He said: "I guess I never gave it a thought. Thanks." He came over and took the lunch. He was stripped to the waist, his trouser belt pinched against long flat-muscled flanks. Sweat showed like oil against the smooth, pale-brown skin and small blurs of dirt lay on his shoulders; he had a wide chest for so small-waisted a man. She saw all this, careful to note it; her eyes held a screened darkness, her expression was steady and solemn. He said again, "Thanks," and took a quick look at the overhead sun, and sat down on the dirt pile to eat. He had big knuckles on his hands, and long fingers; he was slow moving, almost as slow moving as Henry Zimmer—but it was a different slowness.

She said: "You never farmed much, did you?"

"No," he said, "cows are my line."

"What's a cowpuncher doing on a homestead?"

"Well," he said, "I don't know." He sat a moment, thinking of this in the way he thought of so many things, closely and narrow- eyed, worrying it around his head. "Maybe it's because a man's got to put down some roots finally. Nothing for a fellow on the trail, just a bunch of campfires. One day here, one day someplace else."

"I guess you've seen a lot of country. That must be nice. What's it like?"

"Just country," he said. "It ain't ever any different on the other side of the hill."

"Maybe," she said, "it will be different here."

He shrugged his shoulders. "I don't know. Maybe."

It was hard to know what he thought or what he felt when he used that tone. She knew her father and Henry Zimmer—and now even Cam Skelton. They were plain to her eyes; but this man was a stranger; he was not simple to read. Lisbeth reined her pony on to the new homestead shanty, softly sighing to herself, and got down. This house sat against the raw earth. There was no porch; only a single step leading into two small front rooms and a rear kitchen. The smell of wood was clean and strong and resinous; there was nothing here at all, only bare, square walls and two windows and two doors; but she stood in the center of the place, thinking—this would be the bedroom. She would bring the rug for the floor, and the green-dotted curtains. She stood still, trying to reach into his mind and discover why he had built three rooms to the house when most men putting up the first homestead shack only built two.

She moved through the house to the back door. Framed in it, with her white strong arms stretched against the sides of the door and her upper body high and rounded and firm, she watched Law dump the dirt bucket and climb into the well again. He didn't look at her but she knew that he felt her presence, that he knew how close she was to him; he had just eaten and now without delay he was working, as though there was a restlessness he had to wear off. The well was close to the house and she saw that he had placed it so that another room and a porch would enclose it. There wasn't a tree for miles and no shade—nothing but the sage marching out of the flats to the very edges of this place; but she saw the square of poplars around this yard and the garden beyond the well, and the fruit trees. It would not be so long; it would be nice to watch them grow. One thing, though. There would have to be a fence along the edge of the Silver Bow's canyon, to keep the babies from falling into it. Law climbed from the well again, hauling up the bucket. The muscles of his back were long and tight against the brown skin; when he bent over they disappeared and the dotted line of his spine showed white and broad. She said, "So-long," and didn't hear him answer; she rode on home across the canyon and fell to making bread in the warm drowse of the long afternoon, her hands patting the loaves into shape deftly, her thoughts running away from her hands.

At four she saw him riding back on the south rim of the canyon, long before he usually quit work; and stepping out to the rim she watched him stop in the bottom willows. Presently his body was a white and distant blur against the water as he took his swim; later, he rode across the yard. His head was still damp, black and glittering; and his expression was sharp. He said, "I won't be here for supper," and sent his pony townward, sitting in the saddle with that perfect looseness no homesteader could ever match. She watched him until he was vague in the dust and the low slanting sunlight, and would have watched longer; but it was time to make supper. At six Henry Zimmer came out of the canyon, a loose lump on the faithful plowhorse, and her father walked back from the barn and the children suddenly ran in from all quarters of the prairie. She was silent in the supper table's robust racket, close-caught by her thoughts; she was remembering the little things about Bob Law, the way he watched the sky, the way he listened into the darkness, and half through the supper dishes she said, "I am going to town," and at once left the house to saddle her horse.

Dusk moved softly down; westward the band of light lying over the mountains began to narrow and lose clarity. At this hour, the silence was long and deep on the land and all the redolence of the prairie rose around her; the lights of Prairie City began to sparkle ahead. In town she dropped off at Wickert's store.

"I want," she said, "a little bottle of perfume. Just a little bottle."

She paid a dollar for it and was shocked at her extravagance. Night dropped suddenly and in the doorway of Wickert's she watched dust boil in the yellow out-thrown beams of the store lights; shadows made dark banks at wall and alley mouth. Here she stood when Bob Law came from Mike Danahue's saloon farther along the street. The glow of the saloon caught him, his whip-shaped frame, his wide-spread legs and his head bowed beneath the flare of the broad cowpuncher's hat. He had been drinking. She saw that at once from the way he braced himself by the door. He turned from the door and went along the street, reaching out to steady himself by the saloon wall. At the far corner of the saloon, where the stairway ran up to the second floor, he stopped and turned toward the stairs. He didn't move; he just watched them.

Lisbeth got on her horse and went out of town. She wanted to look back to see if he had gone up the stairs, but she kept her eyes to the front. She knew him better now, a little better. Restlessness had driven him into town, to drink; loneliness turned him to the stairs. She thought about that all the way home. Henry Zimmer sat in his corner chair, square and speechless and making sharp little sounds with his lips as he sucked on his pipe; her father had the weekly paper spread under the table lamp's yellow cone, reading with a faint motion of his mouth. Lisbeth went on to her own room closing the door, so that none of them would see the perfume.

Even with the stopper in the bottle a strong fragrance came out. She stood in the room's center, watching light turn tawny as it struck the bottle. She had never owned perfume and it was a little like sin to have it now. But she was thinking of the differences in men. A woman might give herself to Henry Zimmer, and get him; she might hint the same thing to Cam Skelton, and that would be enough. But not with Bob Law. The things he wanted were mysterious in the way they came to him—like the sound of the wind in the sage, like the sight of a mist cloud breaking on the saw-tooth summits of the hills; like, maybe, the scent of perfume on a woman's dress.

She opened the bottle and drew the wet cork once across the breastline of her waist and stood silent a moment, a lightness like a smile on her lips. This was to remind him that the faraway things he wanted were not as far as he thought; then she put the perfume in the drawer of her bureau and crossed back to the yard.

Half an hour later she saw him ride in and unsaddle his pony. He wasn't drunk now; he was slow and certain in the way he laid his shoulders against the corral to make up a cigarette. Matchlight exploded against his face; it was sharp and still restless. He didn't move, he didn't look at her—though she knew he was aware of her; always she knew that, and it was in her mind to cross to him when she heard the quick in-drive of two or three ponies from the dark.

They came rapidly into the yard, three of them, and stopped a little distance from Bob Law who turned away from the corral to face them. One of these men said in a cold, steady way:

"Listen, mister. The time ain't come when a granger can walk into my place, pick a free fight and bust my poker tables all to hell. There's the little matter of a back bar mirror smashed likewise. Maybe you took me for a sucker. Well, sir, I've handled some tough lads in my time and I propose—"

He was a heavy man and he left the saddle and walked on, his boots squealing in the yard's dust carpet. Her father came out of the door and Henry Zimmer came out and her father yelled: "Who's talkin' like that?" But nobody else said anything. The big man made the last few feet on the run, grunting as he struck out with his arms. Lisbeth saw Bob Law's cigarette go to the ground in a shower of fine sparks, she saw Law wheel backward against the corral bars and come forward again. These two were close and they were fighting, the sound of their fists and the sound of their breathing very plain in the night. The big man knocked Bob Law into the corral again; he kept going forward, heavy and determined, meaning to beat Law down. Lisbeth saw Law give ground and stop; he was swift as he moved, he made a circle around the big man and the big man's head began to snap back when Bob Law hit him; the big man said nothing at all but he pushed forward, trying to bring his knees into Bob Law's crotch. His head kept coming up and after that he hit nothing, for Bob Law's long arms, outreaching him, caught him in the belly and in the temples and on the chin; and then the big man went down.

But one of the others, still mounted, suddenly said: "Just hang tight there, mister," and looking over that way, Lisbeth saw a gun pointed at Law. There was a chopping block half across the yard, with an ax sunk into it. Lisbeth ran over and seized the ax; she put it over her head and fled across the yard toward the man with the gun who suddenly said: "Here—get that damned girl—!" But his horse shied away from the downswinging ax and from the corner of her eyes she saw Bob Law duck into his tent and come out again.

"All right," he said, "all right."

He was laughing, or so it sounded to Lisbeth. He had gotten his revolver and held it on the mounted men; it wasn't laughter really, she saw. He was only smiling, and he was pleased with the fight, he wanted to fight. A small streak of blood showed on his chin. He said:

"I guess I've torn up a few saloons in my time, friend. The trail is full of joints like yours. I think you're a tinhorn. Let's just see. I'll count five."

The big man pushed himself off the ground. He said, "Wait a minute. How the hell was I to know you're a cowhand? I thought you was a nester."

Sam Hurd yelled, "What's the difference?"

The big man said: "If you'd been raised in cattle country you'd know. The boys have their habits. Just a little fun at the end of a dreary day. No offense, friend."

Ax in hand, Lisbeth watched these three ride away. Henry Zimmer hadn't moved from the house doorway. Sam Hurd was swearing, "By God, whut you do, Bob?" But Bob Law turned back into the tent.

Lisbeth dropped the ax, suddenly following Law. There wasn't any light in the tent, but the house lamps touched the canvas wall and by this faded glow she saw him. He sat in a chair, slumped over with his hands on his face, and when he looked at her she saw only the weariness of his face. She dropped to her knees and her voice was quick. "I would have chopped his arm off. I would."

She was close to him, close enough for him to catch the odor of the perfume, and she knew he caught it. She always knew when he was aware of her; and he had always been aware of her, never openly showing it. It was something he seemed to fight against. He sat there, his long arms idle, not speaking but looking at her with that same hard set on his cheeks. She knelt back and stood up. Sam Hurd yelled from the yard, "Lisbeth, what you doing there?"

She said: "It just got weary for you, working alone. So you got drunk. Then you went to the stairway that goes above the saloon—"

He said quickly, "I didn't go up."

"Would it have been a help—if you had?"

"I didn't go up," he said again.

"So for you it wouldn't have been a help."

The perfume was a faint incense in the tent's warmth. When he rose from the chair he was a head taller; he looked down, something changing his look. He said: "I've been too close to you. Not good for a man—"

"Being lonely is like that," she said. "I know what you like to eat. I know what you like to hear. I guess I've paid attention to that. I was raised a farm girl. I know what's to be done. You made three rooms. What's the extra room for, Bob? What woman?"

He said slowly, "Is that all there's to it? Nothing else, Lisbeth?"

She said, "A house—with a man and wife in the same bed. It is something. There is a fire in the stove; it is warm when the wind blows, and you are not alone. That is something, too. But not all. The rest—"

She was smiling when she raised her arms. It was the perfume, she thought—the faint call of it, the mystery of the promise of it—which brought him forward. Lisbeth raised her head so that he might not be mistaken about her; and suddenly was within his tight arms, feeling his kiss. This was it, though it had no name. Being very full, and feeling that everything was right. A corner of her mind thought: We will move in when the well is dug. I will bring the extra dishes. He will never have to worry about the house, ever, because I will take care of it. But the feeling grew stronger and fuller, completely crowding her body. She would never regret the perfume. "Because—" And she bent back a little to say in a faint, shy voice: "The rest, the rest is love. That is it." This was what a good marriage meant.