RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

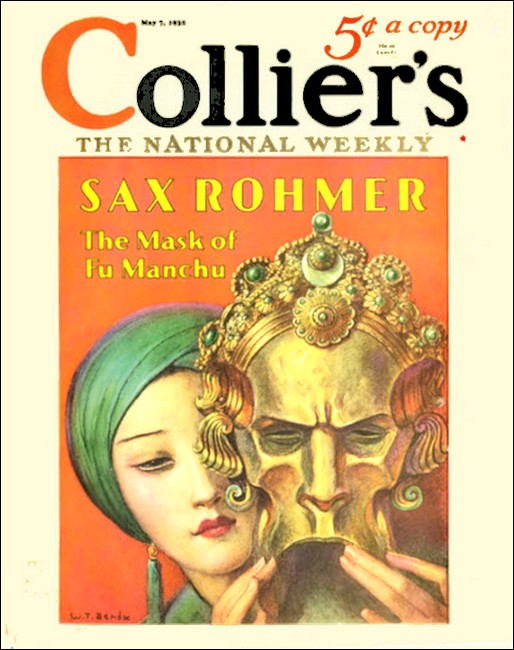

Collier's, 7 May 1932, with "One More River"

JIM IRONS finished the long day's journey underneath a crystal-flecked sky, through silvered shadows. He passed the ruby disk of a campfire on either side, where two trail herds lay bedded for the night, and came against the black outline of Lang's Crossing store. The rumble of the river was in his ears when he turned to the porch of that famous sod structure, the rumble of a risen current and an impassable ford. One mellow shaft of lamplight filled an open doorway and, after dismounting, Irons paused and listened to the idle murmur inside with that calm calculation of a man always figuring what the next bend of the trail might hold for him Then he bowed his head beneath a door frame never built for his height and announced himself with a gentle, Southern drawl:

"One more river to cross, gentlemen."

Four men moved away from a common center, swinging and facing him out of a dim background of laden shelves. The talk ceased with that suddenness which means something more than courteous attention, and as he stood there—taller than any, loose-flanked and bronzed by the lower hot-lands—his indigo glance was witness to the swift sharpening and narrowing of interest. But though he recognized this change for what it was worth, the gravity of his cheeks remained unbroken and presently his turning eyes rested on the most picturesque of the four—a middle-aged man standing beside the store's small counter, a bald-headed man with an orange-red beard trimmed in the uncompromisingly square cut of a Civil War veteran.

"My name is Irons," said he, slurred drawl clinging oddly to the quiet. "You'd be Zeb Lang?"

"I am," said the storekeeper; "but how'd you know?"

"On the trail," observed Irons, "you're a described character. My pony's been pointed toward this speck on the map for seven days."

"Bound north?" asked Lang casually.

"North as far as north goes," assented Jim Irons. He saw a brief meeting of glances and he added a gentle proviso: "But no hurry; I see the river's up."

The inflection of the words roused Lang to politeness. He nodded at the nearest man. "This is Henry Holt, owner of the trail outfit upriver. Beside you is—" and for a moment the storekeeper seemed to sort out his words—"is Mr. Studers, on private affairs." After that, Lang turned to the figure in the deepest shadows. "Killeen—trail boss of the Walling herd below."

Holt, a sound-chested and mannerly individual, alone spoke. "Glad to know you." Studers only inclined his deeply weathered face. He was old, one of those thin, tireless types; he had a self-absorbed manner and his brilliantly black eyes clung to Irons until the latter turned toward Killeen. All he saw of Killeen was a curl of cigarette smoke underneath the flare of a battered hat. He could make out no more, but when he faced the others again, Irons's cheeks were smoothed and masked. It was Holt who suavely broke the lull.

"If you want a riding job, there's a place in my outfit. Through to Fort Benton, Montana."

"Obliged," said Irons. "But I've been on the loose for a month and the leisure's about spoiled me. Never takes much to send an old work horse back to the wild bunch."

They accepted this statement as they had the others, with a weighing reserve. Silence kept returning, falling between them like a leaden barrier. Irons reached for his tobacco, built a smoke, ignited it. He had thought these four to be the only occupants but the flare of his match reached into another corner and surprised him. A girl stood there, half hidden by the rising pipe of a stove; the flickering glow revealed her briefly, insubstantially, and when it died Irons had but the image of a warmly vital face underneath a mass of copper hair. He removed his hat and replaced it in one lazy motion. Lang said, gruff and reluctant: "My daughter, Pat."

Studers came into the conversation with a curious crispness. "You got my name, sir? The whole of it is Jess Studers, United States deputy marshal."

"I was wonderin'," said Irons softly.

Lang stared at Studers with a show of resentment. "I didn't figure you was anxious to spill your business."

Studers's answer was laconic. "Concealment is for the weak. Mr. Irons, how far south are you from?"

"All the way from the Gulf."

"Along the trail?"

"Along the trail."

Studers turned his body better to catch Irons's face in the light. "Any particular business draggin' you north, sir?"

"Wild country up there," said Irons, slow and thoughtful. "Free range. I like to make long dust. In the South a man keeps steppin' in other men's boot tracks. I was born to ride lonely."

"My Lord," broke in Holt, amused, "ain't this side of the river lonely enough? Here's the only white man's house three hundred miles any direction."

Irons studied the burning tip of his cigarette and frowned. "Hard to describe. North—who knows what's north? I don't. That's why I'm goin'."

Studers listened with that peculiar intentness of one seeking hidden meanings. He had his arms locked behind him, his head bent forward on its thin neck. "Pass anybody on the trail? See anything out of ordinary, sir? Hear any stories?"

"No," said Irons. "What should I be hearin'?"

"Where was you a month back?"

"On the trail, where the Fort Fremont road crosses through the live oaks."

The ease and directness with which he reached into his memory and produced the information visibly stirred the group. Holt's air of detached good humor vanished. Lang put both hands on the counter and leaned over it. When Studers spoke again it was with a flat definiteness.

"Right there, a few miles off the trail, one month ago, sir, the paymaster's ambulance, goin' to Fremont with government money, was held up by a single man. Paymaster, sergeant and driver killed. Money taken. You heard no rumor of that on the way?"

"No," said Irons. "That's your reason for bein' here?"

"It is," replied Studers, turned dogged and formidable. "The road agent can't hide out in the Southwest. He'll hit for this river, knowin' there's no authority to take him once he crosses. And he'll ford at this point, needin' supplies."

"You've got it figured," observed Irons.

"My life's been spent in figurin'," said Studers.

The thick silence came again, loaded with unspoken conclusions. Irons dropped his cigarette, ground it beneath a heel.

"I'll be campin'. Any objections, Lang, to my usin' your yard for a bed?"

Lang hesitated and looked to Studers, plainly essaying to catch some sort of a cue from the deputy marshal. But the latter was expressionless, bound up by his own thoughts. After an interval Lang said cautiously: "Roll up inside here."

"Thanks," drawled Irons, "but I'm not used to walls. I'll settle by the porch."

"Not too close," warned Lang. "Pair of copperheads underneath it."

"My kind of company," mused Irons and looked into the corner where Killeen still remained so stiff and speechless. Turning, he went out.

"I know his sort," Holt murmured presently. "Never be deceived by that soft purr. He's got a bottom. Did you see how he took it? Guilty or not, he never turned a hair. Think he's the one, Studers?"

Studers watched the door, face fixed. "Don't know. But I'll find out."

"You got little enough to go on," put in Lang. "No witness, no description."

"He'll give himself away," said Studers. "If it's him he's packin' a lot of bright metal in his jeans."

Killeen moved from the dark in loose, quick strides. All the bony points of his scantling frame poked against the dusty clothes hanging on him. Sorrel sideburns ran below the hat line, a swooping nose held two narrow, Mongol eyes apart, and to either side of a flat jaw the darkly stubbled skin fell into considerable hollows.

"It's him," snapped Killeen. "My outfit was passin' the fort road about then. I saw a lean drink o' water charge through the trees right after a bust o' shots. Sure, it's him."

"Took him a long time to get here," observed Holt.

Killeen answered, irritably insistent, obviously a man hating contradiction. "Well, he'd duck an' dodge, wouldn't he?"

"I'll find out," repeated Studers.

"Yuh better get him now," grunted Killeen, "or yuh won't get him at all."

Studers turned to Killeen with the same direct, studying stare he had used on Irons. But the deputy marshal was through talking, once more self-absorbed; and it was the girl who broke the following silence. She walked from her corner, passed them impatiently and threw out a terse, emphatic phrase that challenged the room's brimming suspicion. "I don't believe it." The storekeeper's eyes followed her through the door with a roused watchfulness.

Irons put his horse on a picket, made a bed of the saddle and its blanket. Standing by the pony, he listened to the crowding waters churn through the night. Upstream the fire of Holt's camp had died to an amber streak along the earth, but downriver the Walling blaze still leaped brazenly at the sky and somebody there plucked a banjo. Irons murmured, "Nighthawks," and faced the porch. The girl was poised there, looking into the northern dark. She stood directly in the beam of house light, straight-bodied, lithe, free-moving; and in the rounding grace of shoulder and bosom was the lure of a womanhood yet unbidden.

So much Irons saw clearly, stirred forward by strange impulses. But next moment caution halted him. Holt and the deputy marshal walked out, turned toward the upper campfire; and directly afterward Killeen slid through the door and swiftly edged away from the light. Irons's eyes clung to the man's shadow as it paused and flattened against the wall of the building, watching the swing of Killeen's head from left to right and the rise of Killeen's arm. Then the trail boss reached the porch edge, dropped off with the soundlessness of a cat and disappeared. Pat Lang, neither seeing Irons nor looking his way, spoke quietly:

"Had your supper?"

Irons walked to the porch, rose beside her. "Thanks. I ate on the prairie."

"So you like a lonely trail," said she, matter-of-fact.

"Always wonder what's on the other side of the mountain," mused Irons.

Wind came out of the northwest—a wind from the wild

distance. Head into it, Irons listened to the upborne yammer of a

coyote, saddest and most primitive of wails. There was a difference

in the air crossing the river. Yonder stretched the leagues of a

land beyond security, mysterious, almost trackless. That wind, with

its feel of outlaw freedom, came a thousand miles with never a

scent of white man or white man's town.

The girl shifted. "You're trying to catch something. I've seen others like you stand here and look out there. Then they go—and they never come back. Whatever is there, it holds them." Turning, she brought her face into the light as deliberately as if she were openly asking him to look at her; and once more he found in that level line across her gray eyes the hint of a reckless spirit suppressed. "Nothing could hold you back?"

He shook his head slowly. "I guess not. What would it be?"

"You're standing in the light," said she abruptly. "Better get out of it. Good night."

He watched her go in, close the door. Returning to his bed, he rolled the blanket around him, wondering.

In the early morning when he rose and went to the river to wash

up, a silver mist clung to the air and crusted the earth. The

current boiled turgidly forward and ragged rents along the bank

showed where the undercutting water had eaten away the soil. But

the flood stage was past, the water level fallen from the high mark

registered on the nearby cottonwood trunks. Reading all this, he

returned to the store. The girl stood on the porch waiting.

"You'll eat breakfast with us."

Lang met him in the kitchen with a guarded courtesy and motioned to a chair.

"By the middle of the afternoon," said Irons, "the outfits will be crossin'. River's dropped four feet."

"You'll be crossing too?" inquired Lang, casually.

"I'll lay in my supplies this mornin'," said Irons.

"One more man leavin' Texas," grunted Lang, taciturn. "When I came here I thought I was years ahead of the tide. But it's flowin' past me now, into another West."

"You'll follow," prophesied Irons. "After a man takes up the march he never quits."

Lang shook his head and fell silent. But later, when the meal was about over and he had listened to the slow talk of the others pass him by, he broke in: "No more for me. I was another of these wild ones, always lookin' for the far side of the next hill. I took my wife from civilized Lou'siana to here. Pat was born in this room. My wife died a little after I got this house up. I tell you somethin', Irons—a woman gets it harder than a man out here. It kills her off quicker. But I was a wild one—and now I've got no wife."

His eyes, increasingly troubled, swept from man to girl. These two were at opposite ends—the grave, contained Irons looking directly at her. She sat square-shouldered toward this seldom-speaking rider, chest rising and falling beneath the tightness of a mulberry waist; one loose coil of the copper hair came down on her white forehead and disturbed the serene line of her eyes. Lang rose and stared as if he had never fully seen her before.

"Pat, you've got the bitter advice of an old fellow. Never marry a wild one that'll drag you from pillar to post and break your heart." Then he went into the storeroom.

She lifted her chin, a deeper stain of color on her cheeks. "Some day there'll be a city here, Jim. Nothing could make you stay?"

He had also risen and now stood with his head tilted toward her, fingers hooked into his belt. "If you fed me like this a week you'd wrap me around your little finger. What would I be doin' in a city? I was born on the edge—always will be on the edge. Somewhere north is my range, for my cattle."

Both her hands fell passively from the table into her lap and she said nothing more. Irons bowed, followed Lang into the store side. Tapering a cigarette, he ordered what he needed, waited out the figuring and then pulled a pucker-string money pouch from a back pocket. He laid two pieces of gold—bright metal—on the counter and closed the pouch with a flip that woke the dull clack of other gold inside. Lang stared at the coins before him during a long interval, and when he lifted his head his eyes were narrowed and severe. Quite in silence he made change.

"I'll leave the grub here till I'm ready to go," said Irons, and went out of the room. The sun was up, the river mist gone. In the first heatless brilliance of morning the prairie swelled and pitched to the horizon's remote edges; and far, far off the faint bulk of high peaks rose blue to the sky. There was a pungency of sage in the air, the steaming smell of a fecund earth. And, halted there, he knew that the rumor of his suspected banditry had spread amongst the outfits and that the coil of trouble tightened around him moment by moment.

For they were all gathered here in front of the store—all of them in the loose attitude of idleness which deceived nobody. Holt and the deputy marshal lounged against the porch. Holt's men rested a little upriver; the Walling crew loitered on the other edge of the yard; and in front of this outfit—situated so plainly and purposely there—Killeen sat on his haunches, drawing circles in the dust with a sage stem.

At Irons's appearance his head jerked up and the Mongol eyes squinted across the distance. His arm movement ceased entirely and for a long stretch of time he held the steady glance Irons bent on him. Then he looked down, went on with his idle dust-writing. Behind him, fifteen hands stood expressionless. One of those—a fiddling little fellow with barrel legs—started forward, to be immediately knocked back by the puncher nearest him. Irons shook his head slightly and swung toward the deputy marshal and Holt.

"You'll be crossin' by afternoon," he told Holt. "Water's fallin' off."

Holt's attitude was detached, amused. "I'm still shy a rider, Irons. And I'm still offerin' you the job."

"You'd take a chance on a stray?"

Holt smiled. "I'm a good judge of strays. You want to get north, don't you?"

"Bound that way."

"Travelin' with me," said Holt pointedly, "may be the only way you'll get there. It's dangerous country." And after a moment he added a casual second thought: "I protect my men."

It was clear to Irons then that this was Holt's bid for a hand in a game he could otherwise only view from the side lines. Somewhere in the course of the last few hours Holt had made up his mind, and now offered help. Irons looked aside to the deputy marshal's lined and inscrutable countenance. Studers's brilliantly black eyes were boring into him. Studers's ears had been absorbing the least lift and fall of his voice.

"Anything new on this road agent?" drawled Irons. "I'm waitin' for him to cross this ford," said Studers, inflexibly patient.

"Think you'll know him? Think you'll—" He broke off, disturbed by one faint fragment of sound rising above the boil and mutter of the river, and turning in common with the others, he saw evidence of a prairie tragedy. Across the stream, out of the farther earth, a man rose from a depression where he had obviously fallen, staggered to the margin of the stream and finally pitched over with the suddenness of collapsed senses.

Holt swore softly. "No horse in sight. Been afoot for a long time. Trouble there—"

"Have to wait out the river," said Studers.

"If he lives that long," muttered Holt.

Irons wheeled, walked to his horse and flung on the gear. Mounting, he passed the ranked men and went upriver toward Holt's camp.

Studers wheeled into the store and returned with a rifle; paused on the porch, threw the gun across his arms and watched Irons's retreating back.

"Yuh fool!" snapped Killeen. "Get him now."

"He'll come back," said Studers. "But if he don't, I'll put a rifle bullet in him."

Lang and the girl appeared from the store and Lang, viewing the shifted scene, asked a puzzled question: "What's he doin' now?"

"Usin' his head," said Holt, plainly pleased. "I told you people—there's a real rider."

Lang was studying his daughter, who stood so strained and absorbed in the doorway. "Better for Irons," he muttered, "if he keeps goin'."

Studers made no reply, seemed not to hear. He was old, stiffened with the patience of a lifetime's making; and so posted he watched Irons while the latter reached a point about two hundred yards above the store, swung and dropped over the river's bank below sight. Soundless and rooted, the spectators fixed their eyes on the running surface beyond; horse and man floated into view, animal turning end for end, gripped by the jaws of the current. Irons bent low, rearing midstream rollers breaking over him. He lost balance, sagged aside; when he fought back, the charging waters had carried him opposite the store and some tangential underthrust shoved him beyond the main channel. The pony went down until nothing showed but its straining muzzle, then rose with the incline of the gravel beach and gained the prairie's high ground. "Easiest half," grunted Holt.

Killeen broke in savagely: "What'd I tell you! He don't intend to help that fellow! Studers, pull up yore gun!"

Irons had ridden back to the prone stranger and halted. Still sitting in the saddle he looked down; looked down for so long a time that even Holt began to shake his head.

"Killeen—you lie!" cried the girl.

Irons reached for his rope, shook it out. He swung to the ground, caught the fallen man, threw him to the saddle. Working now as if time counted, he made a series of ties, snared the fellow's feet underneath the horse, fastened his torso to the horn. So much done, he led the pony upriver again, slapped it into the water and himself took a tow on the tail.

"Told you so," muttered Holt.

There was an offsetting current that seized the pony and flung it into those white crests of the middle raceway. After that there was nothing to be seen; the river had carried its sport behind a lower cut bank.

It was one of the Walling crew who broke the spell. He pivoted, raced to a standing pony and ripped off the coiled work rope hanging by its thong. Killeen's Mongol eyes followed each move with a staring avidity; his voice broke brittle and distinct over the man's head:

"Happy, damn you, stop right there!"

The little man wheeled instantly, rage on his face. "If you think I'll—"

"Do as I say," said Killeen, cold and domineering.

Happy flung the rope to the ground and burst into a fit of passionate cursing. All the rest of that crew began to shift, and when Killeen saw this he sprang off the porch with a purpose so clear that Holt started to walk between. He stopped when he saw Irons climb slowly to the rim of the cut bank and lead the pony forward.

"He's back, Killeen," snapped Holt, "and I'm wonderin' what your hand is worth now—that hand you borrowed without askin'."

Irons halted the pony, loosened the stranger from the saddle and carried him to the porch. "No holes in him," said he. "He's just starved."

The girl crossed the porch, dropped to her knees. Both palms fell on the stranger, but her eyes held Irons's attention and she said one short phrase so low that he alone heard it; his answer was a slight nod and a lift of his head to Killeen. Lang, oblivious to all things but the sight of his daughter kneeling there in front of Irons, turned to Studers with a bitter face and motioned him inside. Studers followed; Lang, wheeling in a far corner, drew two pieces of gold from his pocket.

"Irons paid for his grub with these, Studers. I saw more like it in his wallet."

"Bright metal," said Studers quietly.

"The kind a government paymaster would be carryin'," muttered Lang. "He's guilty!"

Studers watched the storekeeper thoughtfully. "And you're givin' him away? I wasn't thinkin' you'd do that."

Lang's fist closed on the gold. "It's my daughter. I'm losin' her to a man who'll lead her from pillar to post."

Studers left the rifle leaning against the counter. He touched the butt of his revolver absent-mindedly, two deepening furrows creasing the weathered forehead; and he walked out of the room to find the men there in changed attitudes. Pat Lang still knelt beside the unconscious stranger, hands resting lightly on him; the two crews stood on their opposite sides of the yard. But Killeen was retreating from the store, backing toward the river. Irons also had shifted as far as the corner of the porch. Seeing all this, Studers went deliberately across the length of the porch, away from Irons. He stepped into the dust, walked outward a few slow paces and wheeled.

"Irons," said he quietly, "I hear you're packin' considerable bright metal."

"I carry gold," said Irons softly.

"Where'd you get it?"

"Worked for it, Studers. I was paid off in gold." Studers kept on, doggedly calm. "Who paid you off?"

"The boss of a trail outfit."

"A trail boss carryin' gold?"

"This one did," answered Irons.

"What made you quit the trail outfit, sir?" pressed Studers.

The Walling outfit had turned restless.

"I quit," said Irons, "because I couldn't stomach the foreman."

"Why?" pressed Studers.

"He was a murderin' man," snapped Irons, and pivoted to face a raging Killeen. The trail boss yelled: "Irons—may yore soul burn in hell!" His body shook with the erupting force of his gun arm as it struck the holstered weapon's butt and rose. Irons's muscles were smooth with the pressure of an answering draw, his eyes pinned to the thin chest of the trail boss. The blasting report of his gun filled the yard and that bullet, following the path his eyes had made, struck Killeen and staggered him with the force of an ax blow. One long moment Killeen teetered on his heels, the blackness and the boldness of his face shifting to the gray dye of death; and when he fell it was reluctantly, joint at a time—knee, hip and shoulder. Face down in the dust, he never moved again.

Irons wheeled on the deputy marshal, gun trailing. "He left the trail outfit back on the Fort Fremont road for a day's private journey. So he told us. When he came back, the stink of a killin' was on him and he carried gold. He slaughtered that paymaster's bunch, Studers. I knew it and I pulled out. He paid me off with some of the money he took. It was not my place to tell you, nor the crew's. It had to come to this."

Studers made no move toward his gun.

One of the Walling crew spoke: "If you'd asked—we could of told yuh last night—we knowed it a long time."

Holt's voice came off the porch, unmoved: "Killeen's mistake. Men that play hands without first askin' to sit in the game never win."

The girl had risen, jumped from the porch. White and shaken, she cried out to the Walling crew: "And you men let this ride along? You let Killeen have his try at coverin' up? You let Jim Irons take all the chances?"

Irons spoke for them, gently insistent. "It had to come to this, Pat."

The girl came on toward him, shadows across her white face. "Nothing can make you stay, Jim?"

Irons looked across the river, far out to where the distant hills were dimming behind the haze. Then he turned to her: "I have stayed too long. But, if you ask it, I'll stay forever."

She flung up her head, gray glance breaking into a thousand reckless light points: "I never would ask it, Jim! I only wanted to hear you say that. I'll be ready to go with you in half an hour!" She turned and ran to the porch, and saw her father standing there, soundless and sad. "I can't help it," said she, a catch in her throat. "Nothing else counts!"

"I had your mother for five years," muttered Lang. "I've had you for twenty. God bless you, go on."

Irons walked toward the Walling crew, the tall body straight and hurried. "You nighthawks and smoke-eaters, get busy. One more river to cross. Can't you hear the beef a-bawlin' for the wilderness!"