RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

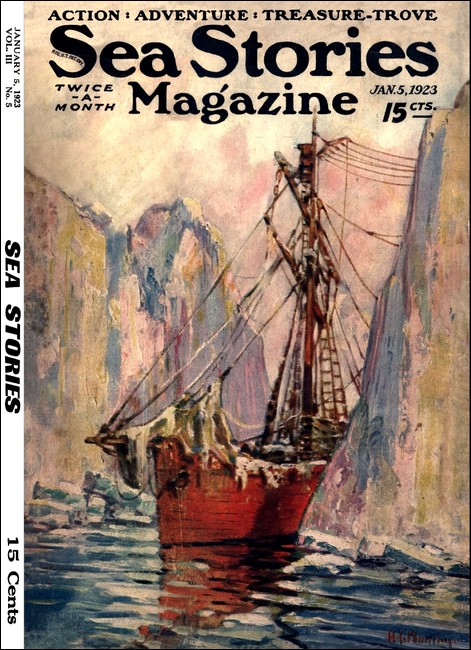

Sea Stories Magazine, 5 January 1923, with "Over the Straits"

The stanch little cannery tender must get her load of valuable red salmon across before the fish spoiled, yet one of the worst storms that had ever swept that coast was raging up the straits. But business is business, even when lives are at stake, and that cargo of salmon represented a small fortune. A story with the tang of salt spray, and quiet, unself-conscious heroism of strong men.

THE Star left the city float in Ketchikan at six o'clock in the evening, headed down Revillagigedo channel, bound for the Prince oŁ Wales Island, thirty-four miles across the straits.

A bad-weather flag had been run up on the post office flag pole just before the eighty-horse-power, seventy-foot purse-seine boat had cast off her lines. There was, so the weather man said, a fifty-mile blow on the outside and the boats were all hurrying for port.

The city marshal, standing on the dock and watching the crew of seven discuss the matter, had given us some practical if blunt advice. It was no time for a consumptive-engined, barnacle- encrusted cannery tender, smelling to high heaven of fish odors, to be out in this kind of weather. Not even though the smell was strong enough to float a battleship. These were his words.

But it was imperative that the Star get across. In her hold were fifteen thousand Sockeyes, choicest of Alaskan red salmon, which had been lifted from the company traps two days ago. Those salmon had to be in the cannery in another ten hours or they would sour, and with Sockeyes at forty cents apiece, and not many to be had at any price, it was easy to see that there was a small fortune in the bottom of the boat.

Nineteen hundred and twenty was a poor fish season and the Star had ranged up and down the coast hundreds of miles, buying up everything offered.

"What do you think, fellows?" asked Bob, our skipper.

"Let's go. Them fish has got to get out of that hold quick." Ed Fraser emphasized his statement by taking a huge crescent- shaped segment out of a plug of Climax medium.

"Rather rough," suggested Milt, the son of an Alaskan mining magnate who was out for his fall school money.

"Hell, I'd just as soon drown as be on the same boat with sour fish," spoke up Al, the engineer.

Charlie, a short and pudgy bald-headed German grinned doubtfully and squinted toward a leaden sky. Charlie scarcely ever said anything. It took too long to talk.

"What do you say, Hal?"

I ran my fingers through a luxurious three-month beard—fully an inch or an inch and a half long—and tried to look judicial. Most of all I wanted a good long sleep, after having been battered around the wheelhouse through a week's steady running in rough water. Then I wanted to have a night off in Ketchikan and limber up the rusty springs of joviality; we hadn't been near a town for a month. Added to these reasons was the gale outside.

"Urn," I said, trying to convey an impartial answer.

"How's the engine running, Al?" Bob queried.

"It's all right, if the carburetor'll only keep mixin' like it has been th' past few days."

"Got plenty of oil and gas?"

"Yep. Both tanks full."

"All right; let's go, gang. What say?"

"Go she is."

"Ed, you better lash down everything above deck—Charlie, giv'm a hand—Hal, take first trick at the wheel—Ahoy, on the dock, let go our lines will you?" and shortly, with a farewell screech we were out in the channel.

A short distance down we passed a subchaser on our port side, coming in. As I took a spoke in the wheel I wished very fervently that I was on that boat, bound back to the dock. I clawed around with my free hand and drew up the tops of my boots, and reached over for my oil coat which hung on a hook. This sounds strange, I know; but there is a curious sensation of dampness that pervades one when running in a heavy sea, and be the pilot house ever so comfortable and warm, the sight of wave after wave piling up and smashing over the bow always makes one mechanically reach for boots and slicker. I was beginning to see things, though we were still in calm water, comparatively.

The run down the protected channel was quickly made. We passed a score of cannery tenders, all bound for town. Most of the men on them waved at us wildly and pointed the other way. I gave them all a debonair toot of the whistle, a bit of hypocrisy that soothed my feelings considerably.

The trap door connecting the pilot house with the galley opened and Bob entered, wiping his mouth on the back of his jacket.

"All right, Hal, I'll take 'er, while you get a bite to eat."

"You better start collecting all the spare rope you can find, Dad," I said to the cook as I squeezed into the diminutive galley. "Enough to lash yourself down with, too."

Dad was a spry young adventurer of some seventy-two years. He had fought nearly all the Indian tribes in the Northwest, it seems, under General Miles, when a young buck of eighteen, and somehow, now at the other end of the cycle, the lure had returned to him and he had taken to the water. This was his first sea job.

"Gwine ter be rough, I reckon, heh? Well, let 'er come—yerroo-oop!" He let out a wild war whoop. Suddenly he made a grab for the coffeepot which rocked wildly on the stove. We were weaving in and out of the protecting islands between the straits and the channel.

"Yeroop, yourself," I said, hastily gulping down my coffee and making for the door. "You'll be using worse language than that in a mighty short space of time."

"Heh! Git out of my kitchen!"

It was growing dark when I retook the wheel. Overhead the sky was a mottled gray-black. The wind was beginning to sing through our mast and rigging. On either side were the blurred outlines of the islands we were hugging. In another few minutes they would be behind us, and we would be out in the straits bucking a wind that hit us on our port quarter.

The waves were running higher now, and the boat began to pitch and roll. Ahead I could faintly make out the jagged, angry outlines of the sea. The crew had scattered. Al was down by his precious engines and Charlie had gone with him. Milt and Ed were sitting on the bench behind me. In the gloom I could make out the glow of their cigarettes, reflected in the window-panes. Bob, beside me, was peering intently through the fogged glass.

Crash! Our bow shot up suddenly as if some giant hand down in the depths had punched it. For an instant we hung there, then the sea dropped away and we lunged down into a deep gray gulley and rolled dizzily on our side; a thick, twisting wall of water crashed down on our foredeck with a jarring, smashing impact and dashed up against the front of the pilot house.

I braced myself on a cleat, hung to the wheel, and twisted it sharply to get back into the wind. Bob slipped and seized the handrail. Behind me I heard the thud of two soft bodies hitting the floor, and from the galley came the crash and clatter of pans and dishes, mixed with the shrill treble curses of Dad.

We were out in the straits.

"What's your course now, Hal?" asked Bob, face glued straight ahead.

I switched on the binnacle light and peered into our Standard Navy compass. It was a large thing, too large for our boat; for, like a rat terrier, we pitched and plunged, rocked and rolled, with short, choppy motions, while our "instrument was fitted for a larger ship that rolled and swung with a slow wallow. I watched the card recover from a long, deliberate swing and estimated its arc.

"About north, a quarter east," I answered. "But she's swinging too slow to be accurate."

"Ease her off to starboard a little more. We're headin' way below Morey Light now."

The wind, hurling itself through Dixon's Entrance, fifteen miles below, came sweeping, tearing up the straits. We were right in the teeth of it. The singing in our mast changed to a low, ominous moan, mounted higher, broke into a screech, then still higher, higher, into an insistent, piercing shriek.

"Bob!"

"Huh?"

"Did we tighten up that front stay last time we was in?"

The front stay is one of the four wires supporting the mast. It runs from the top of the pole down to the bowsprit, where it is clamped. Often the clamps work loose, allowing the wire to swing slackly, rendering it easier for the pole to break under stress.

There was a moment's silence. "Nope, we didn't."

"An' them clamps was loose, too."

"Yep," came the succinct answer. Bob hadn't moved an inch from the window in the last quarter of an hour.

"If it breaks loose—"

Another dizzy roll, sending us far to the side, interrupted the sentence. The shriek of the wind crept up a note. I could just make out, directly in front of us, the twisting, contorting water. Now it would pile up to a sharp peak and the jagged edges would be whipped off by the wind, driving against the front of the pilot house with the sharp rattle of machine-gun bullets. Now we would meet a huge wave head on and the boat would stagger back while the spray went flying high in the air. Now we went plunging into a trough with the sickening drop of an express elevator, while the foredeck completely disappeared from Bight, buried under the seeming, boiling eddies of water. Then we would labor to the surface in time to meet another onslaught.

We were struck from the side and went reeling, careening over with our bottom half out of water and the runway on our under side completely submerged. I clutched the wheel tightly to keep from going smashing against the wall, while time and again Bob hung suspended, head and shoulders over me, for a long breathless instant, his body standing out in shadowy silhouette against the side windows. Then we righted ourselves, shipping a load of water that went sweeping, sliding over the deck and came spurting into the wheelhouse, under the doorsill. Now and then we would stand on our stern, bow completely out of water, like an angry bear on its haunches, and the next instant we would be slammed violently against the front of the house, stern boosted up, nose deeply buried, while I twirled the wheel vainly and prayed for a speedy recovery.

"Must be wilder'n all-get-up outside the islands," remarked Ed, as we went hurtling down into a giant hollow.

"Must be," returned Bob, eyes glued to the pane. "Good blow here in the straits." We came out of the trough with a leap—high into the air we went.

"Wish I had a good hot cup of coffee," I said after a century or so.

"Huh! There ain't nothin' stickin' to that stove 'ceptin' th' polish. Chew of t'bacco help?"

I could hear nothing from the kitchen; evidently there wasn't anything left to fall from the shelves.

We were struck sharply on the port side—another heavy impact from the front—and over we went. Over, over—I clutched the wheel tensely and tried to take a spoke. The water came spurting through the cracks of the door. It seemed as if Bob's whole body was suspended over me, motionless. Some fragmentary recollection of a hanging sword came to me. An eternity we hung there, then slowly, slowly came back.

Ed stirred. "Bad one." It sounded more like a whistle than an articulation of words.

I heard the trapdoor open and some one struggle through, then a long, lurid, wind-swept string of oaths. "An' ef I ever gits off'n this here lame-halted critter I'm going to reetire fer th' rest of my life in th' mountings."

"Yeroop," said I in a very mediocre imitation of a war whoop. I'm not very good on war whoops.

Unk! Bang! I heard all three men go crashing down against the wall. We were thrown high into the air, stern down.

"Say," spoke up Ed, suddenly. "If our seine table should be jarred off'n its rollers it'd go overboard in about ten seconds." Our fifteen-hundred-foot seine rested on a revolving table on the stern, with nothing to hold it down but its own weight.

Barnes shifted his gaze for the first time. "Ed, if we lose that net we'll go to hell in a handbasket. That's all's helping us to ride this blow."

"Can't pitch much worse. We're roll-in' our tail off now."

"That table should have been lashed."

"What're you goin' t' lash it to? Hain't nothin' there."

"We might have passed a line around it and back to the towbitts. That would have held it some."

"Well, mebbe."

"Only trouble is in getting back there," continued Bob. "That deck ain't out of water ten seconds at a stretch."

"Where's that half inch rope we had?" Ed asked suddenly.

"In the chest you're setting on."

I heard him fumble about.

"What're you going to do?" asked Bob.

"Tie it around me—you'n Milt hang to th' other end and pay it out as I go. I'll try to get back there by hangin' to the guard rail. Pull her in when I holler."

"Won't hear you—too much noise."

"Well, keep your eyes peeled."

"Can't see."

"Well, dang it, use your judgment!"

We lurched over on our side and he had to wait a minute or so before daring to open the door.

"Any relations you want me to notify?" I asked, spinning a useless wheel.

"Go to—" the rest of it was lost in a hurricane of wind, noise, and salt water that tore in as he opened the door. It literally blew him backward. He caught himself, tried again, got outside, then we lost him in the angry blackness. Bob and Milt paid out the rope slowly, both hanging to the handrail and braced against the door to hold it partly open.

Again we shot up into the air, hung, and slid drunkenly back into a black abyss. The two men pulled frantically at the rope, dragging Ed back by main force, jerking him inside, and slamming the door just as a huge mountain came crowding, spilling over our side.

"No use, can't be done," panted Ed. I could hear the water cascade from his clothes.

It was absolutely dark now. We were in a vast empire of blackness, filled with millions of weird, screaming voices.

Suddenly I heard, in the rhythmical throb of the engines below me, a catch, a cylinder missed fire, coughed, and caught the rhythm once again. In that moment my heart lost a beat, and I know I must have cried out some unintelligible thing to the gloom.

To be buffeted about in a vast inky inferno of tumult, not knowing where one is, not knowing what reef is ahead of one, not knowing what the next wave will do, not knowing when some part of the rigging will break, is a trying situation. Yet the powerful, sturdy engines are driving on and on, fighting the waves blow for blow, keeping the boat in the face of the wind, pushing forward toward a calm harbor, foot by foot. And from that dogged persistence men take courage. But when they stop, the only weapon against the elements gone, something sinks and dies out in a man's heart.

There is always a lurking fear in the mind of those who go out to sea in gas boats that they may develop engine trouble, in bad weather. Gas engines are not the most dependable means of locomotion.

The gloom was beginning to stifle me. My nerves were on edge. I checked a panicky impulse to swing the wheel hard over to where I thought land ought to be. I was beginning to doubt the compass. Back of me I heard the clock sound eight bells, twelve o'clock, midnight. We had been out six hours on a trip that ordinarily took two, and hadn't yet picked up the far-away glimmer of the beacon that marked out the entrance into calmer, quieter waters....

Bob was peering into the sweeping, whistling, shrieking blackness.

"Course now, Hal?"

"North, a quarter east, about."

He moved impatiently. "Ought to have picked up Morey Light long ago."

"Don't suppose the dang thing's still on the bum, do you?" queried Ed, groping his way forward and wiping clear a place on the foggy pane.

Morey Rock Light had been out of order for a month or more and we had constantly notified the superintendent of the Light Service at Ketchikan about it.

"Shouldn't be. We sure are out of luck if it is. Blow's taken us 'way off our course; must be somewhere near Kiegan's Chuck. If we can't pick up that Light we'll have to beat up and down here all night—and take our chances."

Both men pressed their faces against the windowpanes.

I swung the wheel to port after coming out of a trough and tried to force all my energy into one intense gaze that would bore a hole through the blackness. But my eyes were tired and the lids burned in an irritating fashion. My arms were bruised and sore. With each successive pitch and roll of the boat my weary leg muscles responded less readily. I was tired, so darned tired! With a supreme effort I nursed the spokes over and dug my feet into the deck cleats as we made another sickening, dizzy sideward roll. Then through half consciousness I heard a voice close to me.

"Hell, Hal, I plumb fergot. You been wrassling that wheel for six hours." Ed grasped the spokes. "Lemme have it. You better see if you can't grab off a couple of winks."

I came out of a doze, pried stiff, cramped fingers loose from the wooden spokes and lurched, stumbled backward, feeling for the bench. I steered around it, crouched down on the wet floor, braced my back against the bench and my feet against the wall. A long roll swung the boat over again until I was lying almost on my back, feet high in the air. Suddenly I didn't care a hang if the boat floated or sank. Too tired. But before I went to sleep a satisfying thought came to me. Outside the cabin nature had let loose all the violent elements in her box of tricks, all against this little boat pitching and tossing drunkenly on a sea of monstrous ridges and abysmal valleys, zigzagging crazily through a night as black as the pit, rolling and heeling to a wind that ripped up oceans; while inside the pilot house, an insignificant cell of quietness in all this riot of fury and noise, seven pygmies stared through flimsy glass windows and defied all the combined efforts of the elements of turmoil. The last words I heard were:

"Now where in hell is that Light?"

It was a boat with an exceedingly clean deck that came chugging into Cannery Inlet about eight in the morning, a boat with a crew one third awake. We scraped four pilings and crashed through a rowboat float before docking at the fish conveyor. We heard exclamations of wonder as we threw out our lines. About us we could see traces of last night's storm on the beach, even in this haven.

"Gosh, man! You didn't come across in that storm?"

Bob lit his pipe and turned a sleep-laden face to the inquirer, the cannery owner. Then he climbed into his bunk, clothes, boots, pipe and all'.

"Unhuh. Li'l bit rough." And he dropped off to sleep in the man's face.

Back in the galley I could hear the old cook making breakfast to the tune of an exceedingly ribald old song:

"Oh, were yez ever in an Irishman's shanty,

Where money was scarce and whisky was planty—"

The owner turned to the rest of the group. "But wasn't it rough?"

"Oh, it blowed some," said Ed, making for his bunk in the fo'c's'lehead.

"Rather rough," added Milt, which was his second statement since leaving Ketchikan the night before.

Charlie, fat, bald, and German smiled wisely and made for the kitchen, from which came the odor of fried ham.

"Um," said I, trying to straddle the fence. I would like to have enlarged on that trip. I felt it deserved grander treatment. It needed an epic strophe and sonorous epithets. But how could a blase old sea dog of twenty-one do so without losing caste? I followed Charlie into the galley for breakfast.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.